Paul taught that “there is neither Jew nor Greek” (Galatians 3:28). The Jewish law had been a forerunner, a tutor: “For by one Spirit are we all baptized into one body, whether we be Jews or Gentiles, whether we be bond or free” (1 Corinthians 12:13). The Christian was to be saved, not by the letter of the Jewish law, but by the spirit of the Jewish faith in a righteous God.

Paul was a mystic who sought to transcend the world and the flesh, a gifted spiritual adviser of ordinary men and women troubled in their everyday lives, and an able administrator of a growing church. He was firmly convinced that Christian truth was not a matter of habit or reasoning, but of transcendent faith. He expressed a tension between this world and the next, between the real and the ideal, which firmly marks Western society. Paul’s symbol for it was the mystic religious act known as communion. Christians are children of God who are destined to eternal bliss. But on this earth they must live in the constant imperfection of the flesh, always aware that they are at once mortal and immortal.

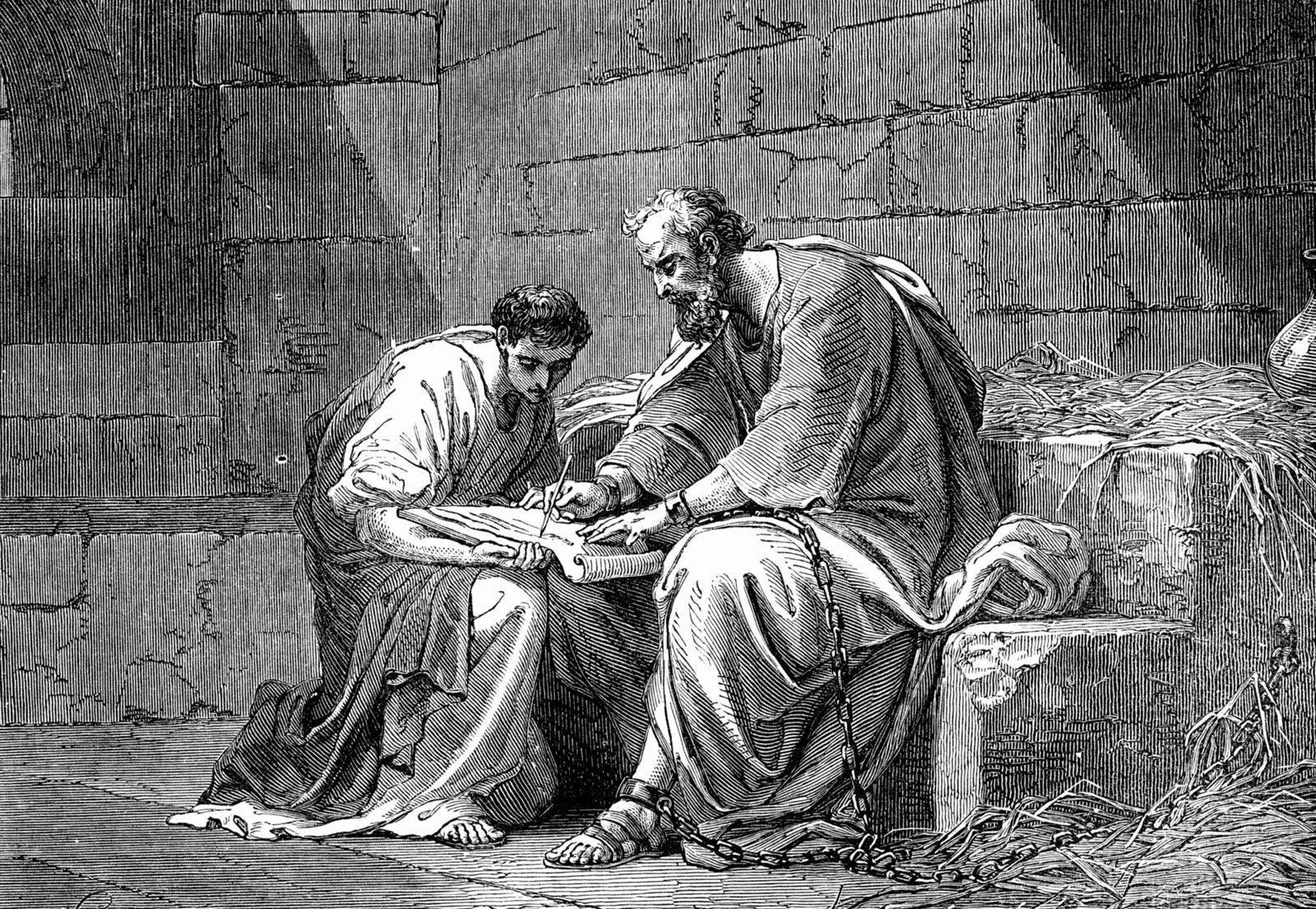

The Pauline epistles deal frequently with church discipline. Here we see Paul keeping a firm hand over scattered and struggling Christian congregations in the lands to which he traveled. He tried to tame the excesses, to which the emotionally liberating doctrines gave rise, urging the newly emancipated not to take their new wisdom as an opportunity for wild ranting (“speaking in tongues”) but to accept the discipline of the church, to lead quiet, faithful, firmly Christian lives.

Paul was not one of the twelve apostles, the actual companions of Christ, who, according to tradition, separated after the crucifixion to preach the faith in the four corners of the earth. But he has been accepted as their equal. Of the twelve, tradition holds that Peter went to Rome, of which he was the first bishop, and was martyred there under Nero on the same day as Paul. Thus the Church of Rome had both Peter and Paul as its founders.