-

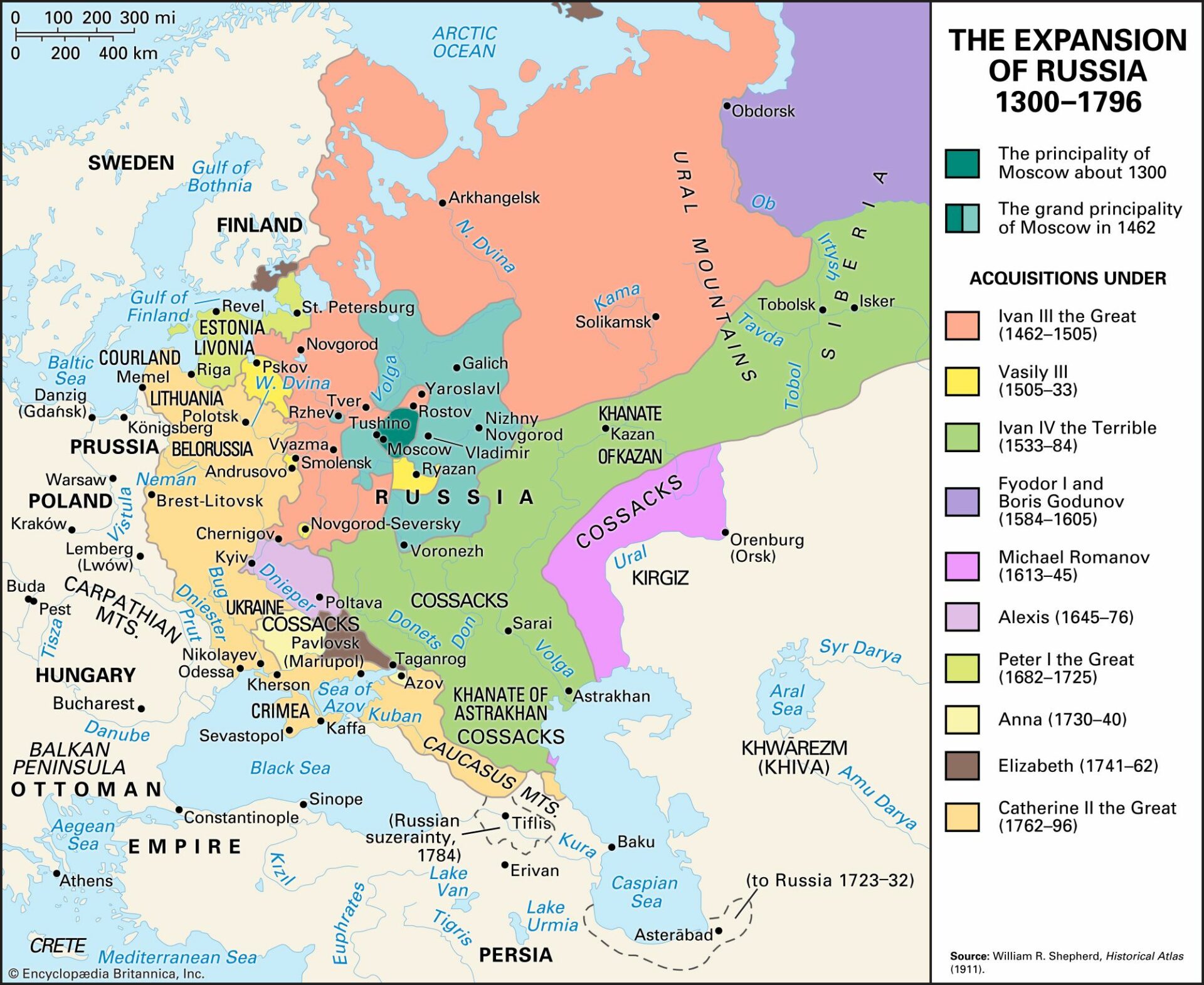

Russia and Peter the Great, 1682-1725 | The Old Regimes

Even more spectacular than the rise of Prussia was the emergence of Russia as a major power during the era of Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725). In 1682, at the death of Czar Fedor Romanov, Russia was still a backward country, with few diplomatic links with the West and very little knowledge of the outside…

-

Prussia and the Hohenzollerns, 1715-1740 | The Old Regimes

Prussia’s territories were scattered across north Germany from the Rhine on the west to Poland on the east. Consisting in good part of sand and swamp, these lands had meager natural resources and supported relatively little trade. With fewer than 3 million inhabitants in 1715, Prussia ranked twelfth among the European states in population.

-

The Newcomers | The Old Regimes

Significant new players were emerging onto the international stage throughout the first half of the eighteenth century. The most important of these would be Prussia and Russia. Two once-powerful states would suffer as a result: Poland and the Ottoman Turks. The result would be a series of diplomatic and far-reaching political changes and growing international…

-

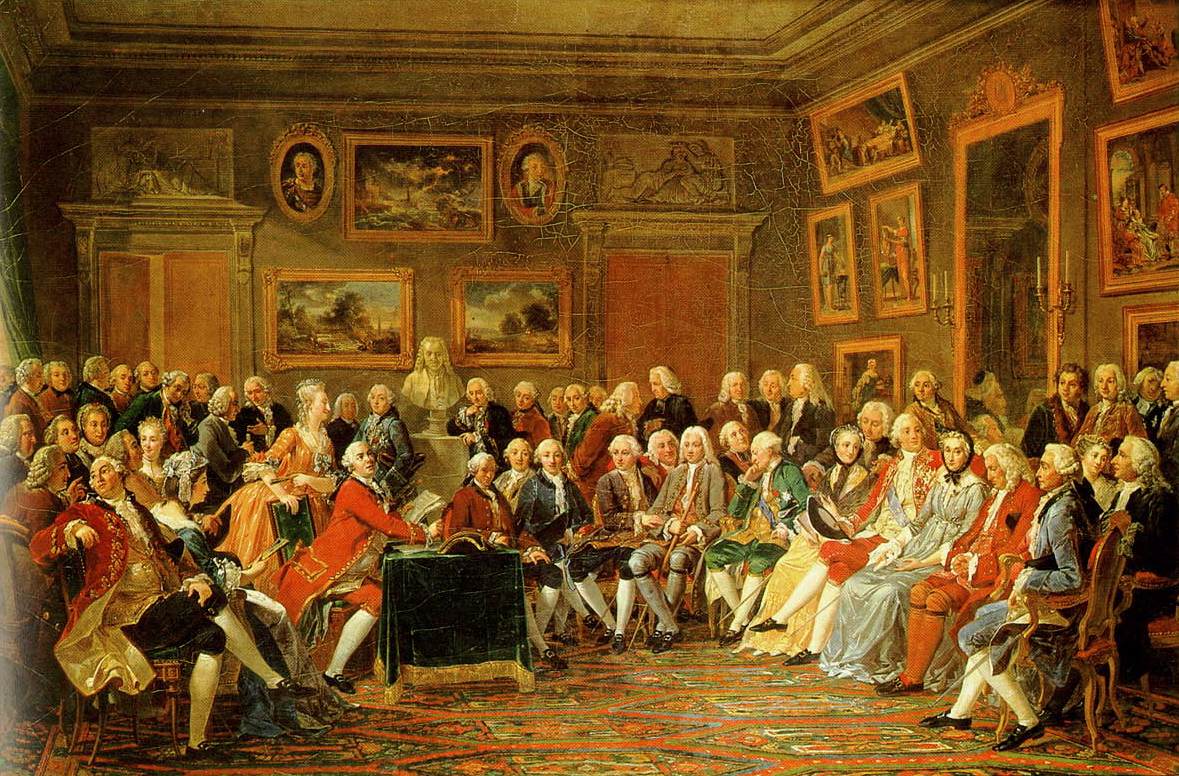

An Age of Manners

In 1729 a French guide to behavior for the “civilized Christian” covered such subjects as speech, table manners, bodily functions, spitting, nose blowing and behavior in the bedroom. This guide to good manners was reissued with increasingly complex advice through 1774, though with significantly changing emphases, as certain behavior (blowing one’s nose into a kerchief…

-

Other States of Western Europe | The Old Regimes

Spain was the only other state in western Europe with a claim to great power status. Sweden and the Dutch republic could no longer sustain the major international roles they had undertaken during the seventeenth century. The Great Northern War had withered Sweden’s Baltic empire. The Dutch, exhausted by their wars against Louis XIV, could…

-

France, 1715-1774 | The Old Regimes

Where Britain was strong, France was weak. Barriers to social mobility were more difficult to surmount, though commoners who were rich or aggressive enough did overcome them. France suffered particularly from the rigidity of its colonial system, the inferiority of its navy refused to allow the colonies administrative control of their own affairs.

-

Britain, 1714-1760 | The Old Regimes

In the eighteenth century British merchants outdistanced their old trading rivals, the Dutch, and gradually took the lead over their new competitors, the French. Judged by the touchstones of mercantilism—commerce, colonies, and sea power—Britain was the strongest state in Europe.

-

The Established Powers | The Old Regimes

Britain and France were the dominant European powers of the eighteenth century. At the beginning of the century Spain was still powerful, though it would decline throughout the century. The Dutch remained prosperous, while the once-powerful Swedes declined even further. Economic change was the touchstone.

-

The Beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, to 1789 | The Old Regimes

By increasing productivity and at the same time releasing part of the farm labor force for other work, the revolution in agriculture contributed to that in industry. Industry also required raw materials, markets, and capital to finance the building and equipping of factories. Thus the prosperity of commerce also nourished the growth of industry.

-

The Agricultural Revolution 1750-1900 | The Old Regimes

The agricultural revolution—the second force transforming the modern economy—centered on improvements that enabled fewer farmers to produce more crops. The Netherlands were the leaders, producing the highest yields per acre while also pioneering in the culture of new crops like the potato, the turnip, and clover.

-

Commerce and Finance, 1713-1745 | The Old Regimes

Many of the basic institutions of European business life had developed before 1715—banks and insurance firms in the Renaissance, for example, and chartered trading companies in the sixteenth century. Mercantilism had matured in the Spain of Philip II, in the France of Louis XIV and Colbert, and in Britain between 1651 and the early eighteenth…

-

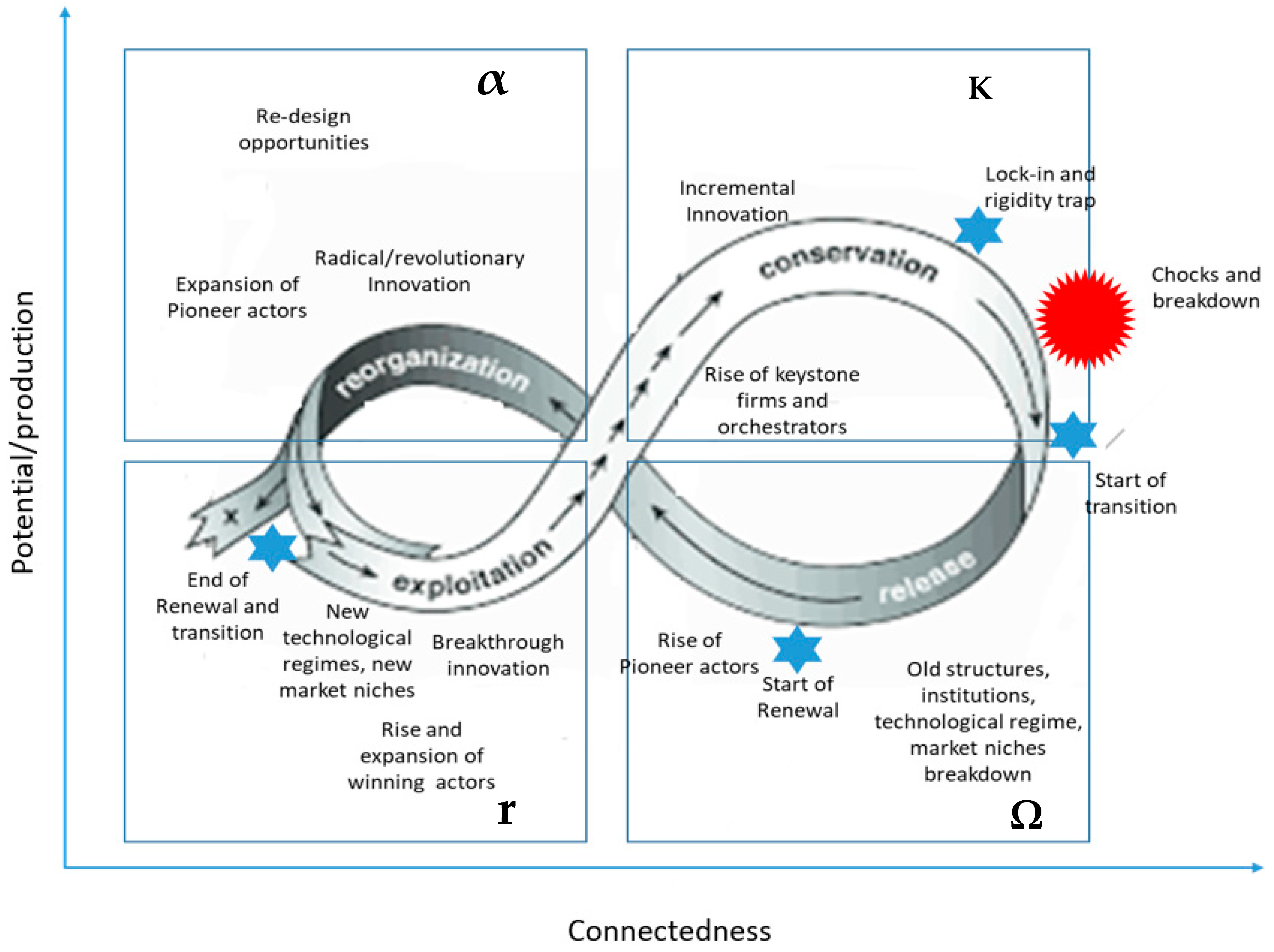

The Economic "Revolutions" | The Old Regimes

The changes that undermined the Old Regime were most evident in western Europe. They were in some respects economic revolutions. In the eighteenth century the pace of economic change was slower than it would be in the nineteenth or twentieth, and it provided less drama than such political upheavals as the American and French revolutions.…

-

The Coffeehouse

The thriving maritime trade changed public taste, as it brought a variety of new produce into the British and Continental markets. Dramatic examples are the rise of the coffeehouse and the drinking of tea at home.

-

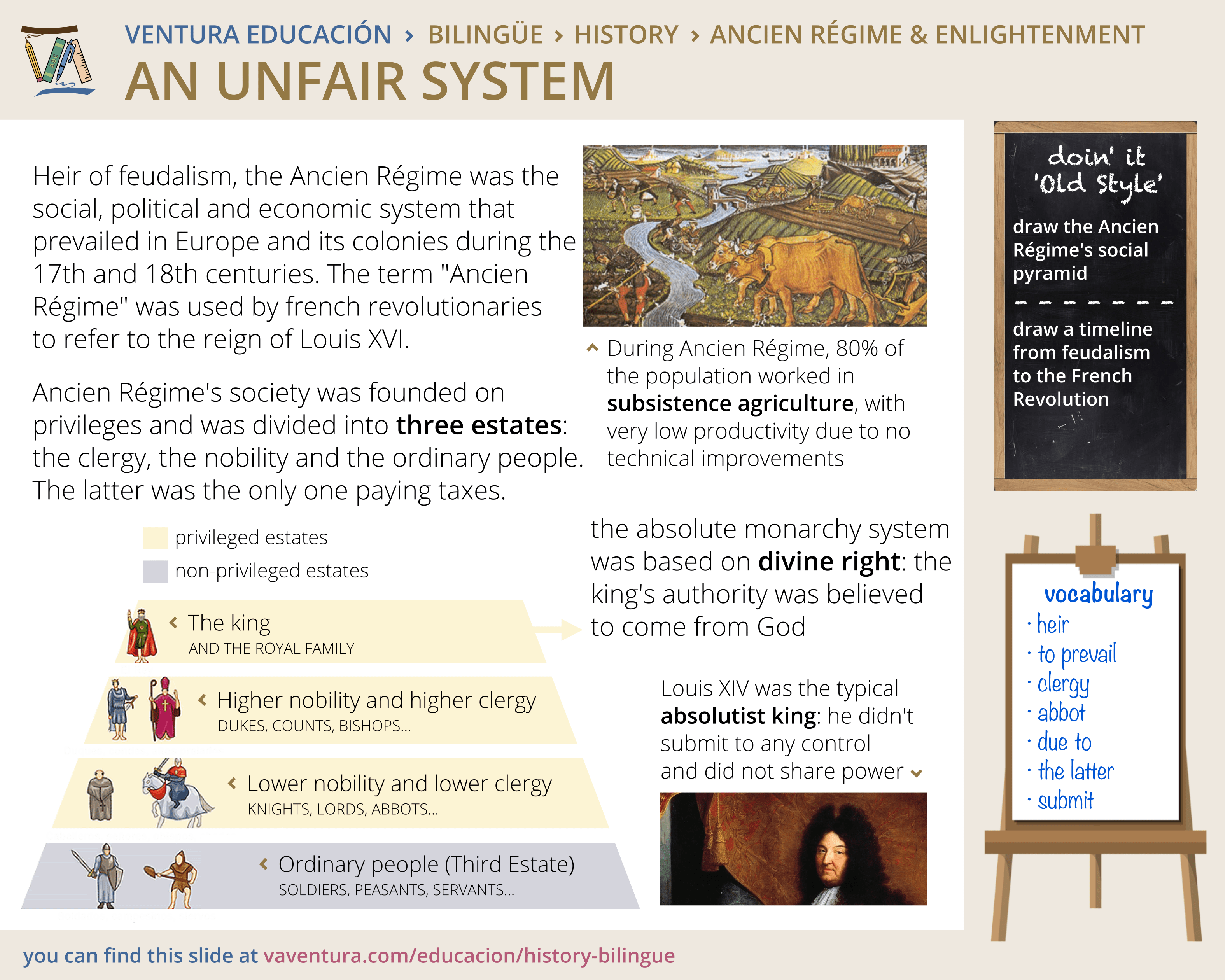

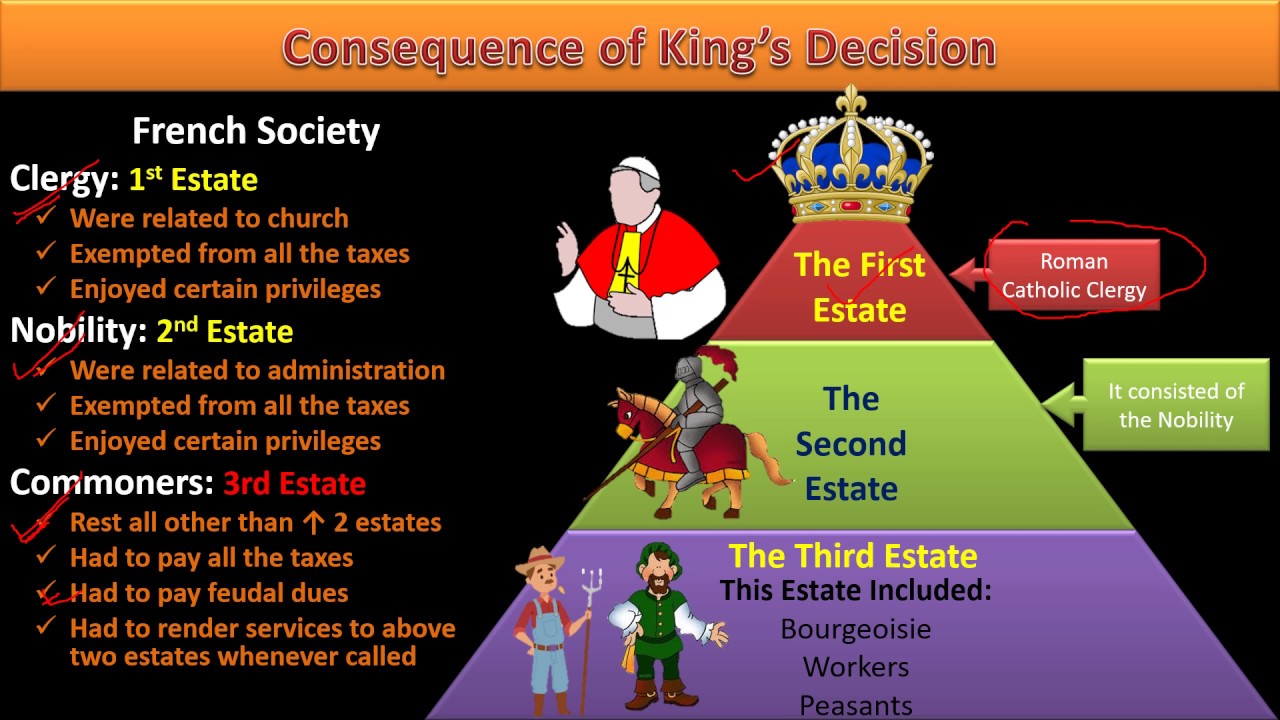

The Old Regimes

The term Old Regime is used to describe the institutions prevailing in Europe, and especially in France, before 1789. This was the “Old Regime” of the eighteenth century, in contrast to the “New Regime” that was to issue from the French Revolution. On the surface, the Old Regime followed the pattern of the Middle Ages,…

-

Summary | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

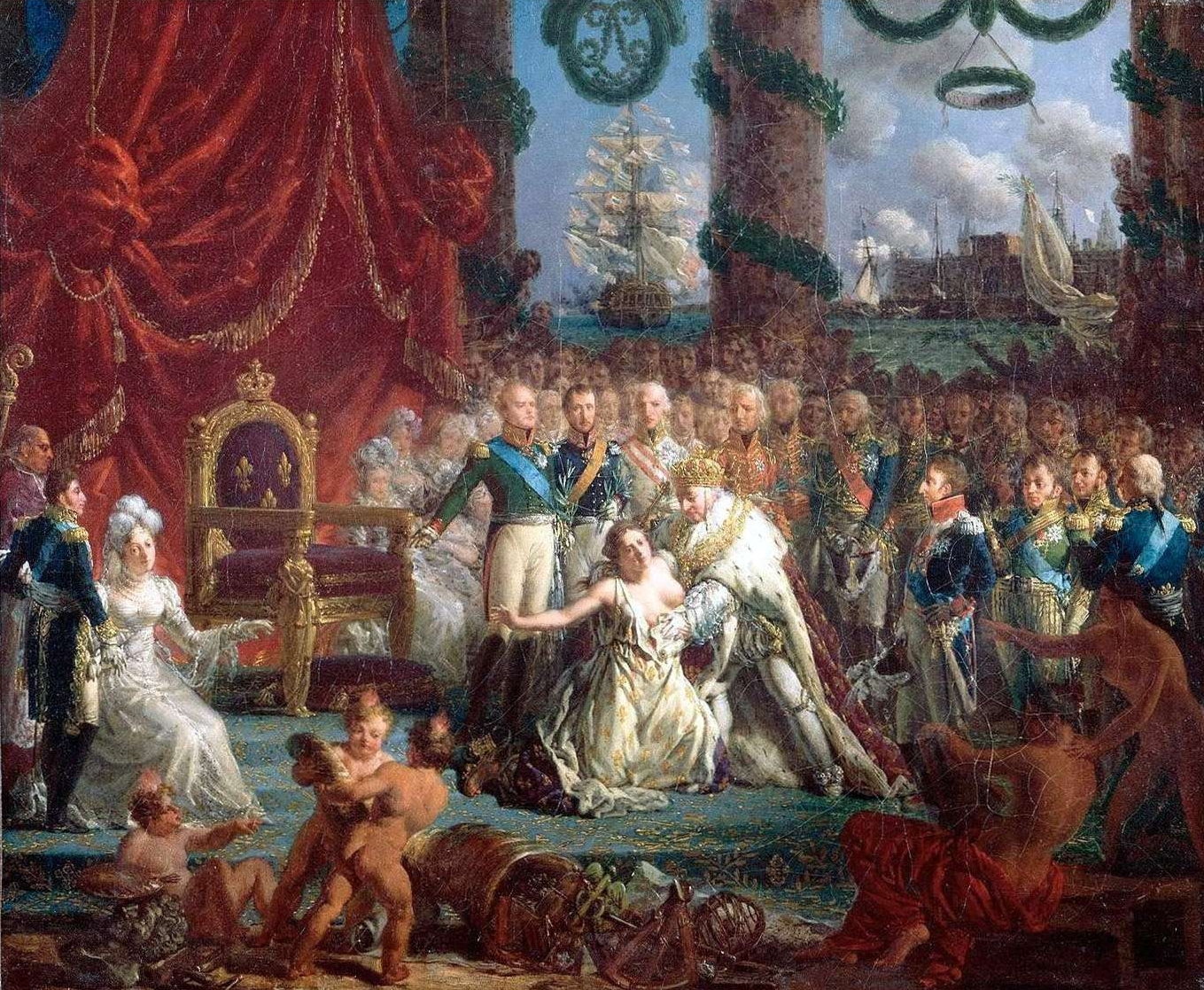

The seventeenth century was dominated by France. During the reign of Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu created an efficient centralized state. He eliminated the Huguenots as a political force, made nobles subordinate to the king, and made the monarchy absolute. Louis XIV built on these achievements during his long reign. Louis XIV moved his capital from…

-

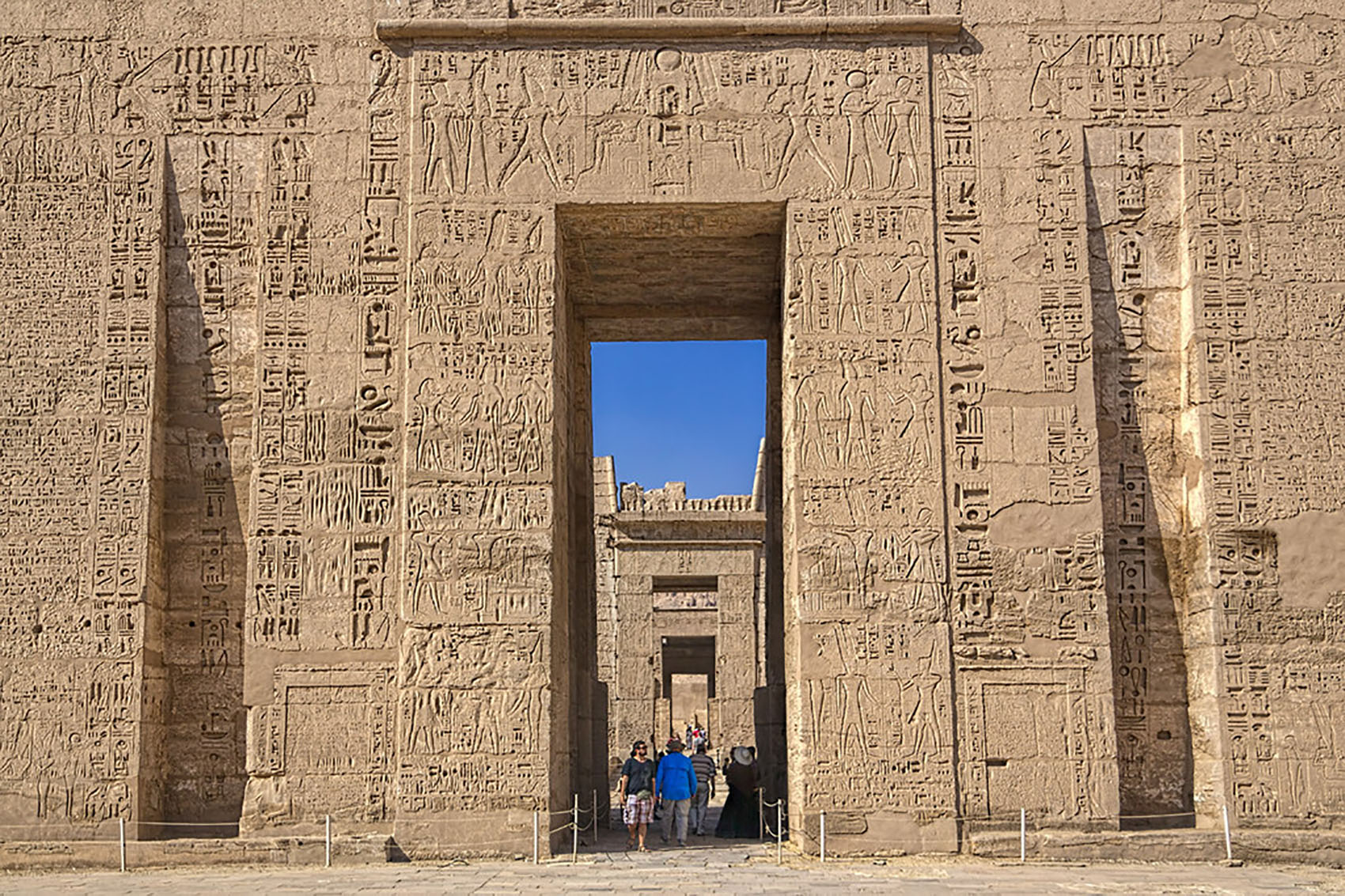

Who Built the Towers of Thebes?

In the seventeenth century the underclasses, that unspoken for and, for the historian who relies solely on written records, unspeaking mass of humankind, began to speak and to answer the questions posed in the twentieth century by a radical German dramatist and poet, Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956): Who built Thebes of the seven gates? In the…

-

Social Trends in 17th Century Europe | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Throughout the seventeenth century the laborer, whether rural or urban, faced repeated crises of subsistence, with a general downturn beginning in 1619 and a widespread decline after 1680. Almost no region escaped plague, famine, war, depression, or even all four. Northern Europe and England suffered from a general economic depression in the 1620s; Mediterranean France…

-

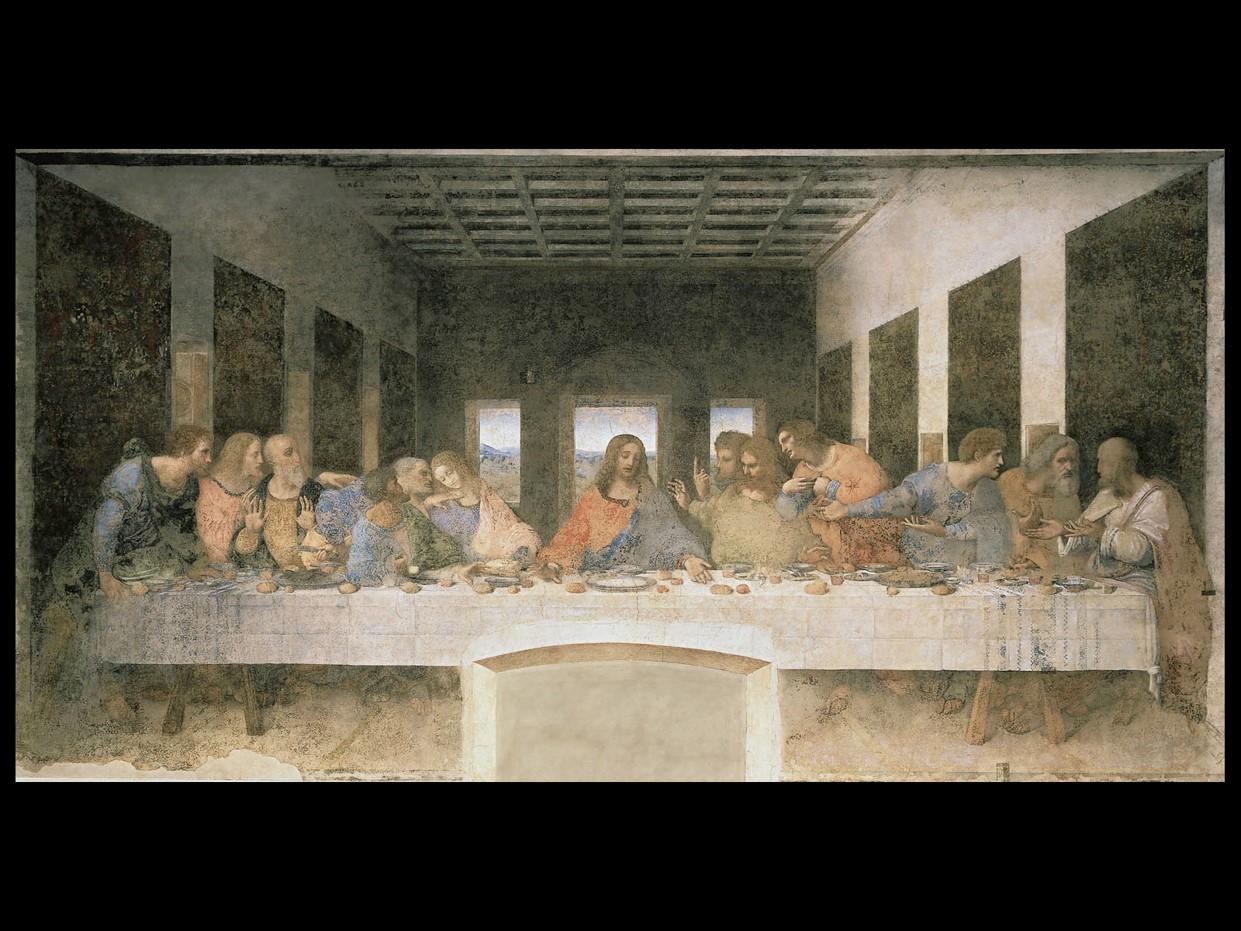

Music in The Baroque Era | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Baroque composers, especially in Italy, moved further along the paths laid out by their Renaissance predecessors. In Venice, Claudio Monteverdi (1567- 1643) wrote the first important operas. The opera, a characteristically baroque mix of music and drama, proved so popular that Venice soon had sixteen opera houses, which focused on the fame of their chief…

-

Architecture and the Art of Living in The Baroque Era | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Baroque architecture and urban planning were at their most flamboyant in Rome, where Urban VIII (1623-1644) and other popes sponsored churches, palaces, gardens, fountains, avenues, and piazzas in their determination to make their capital once again the most spectacular city in Europe. St. Peter’s Church, apart from Michelangelo’s dome, is a legacy of the baroque…

-

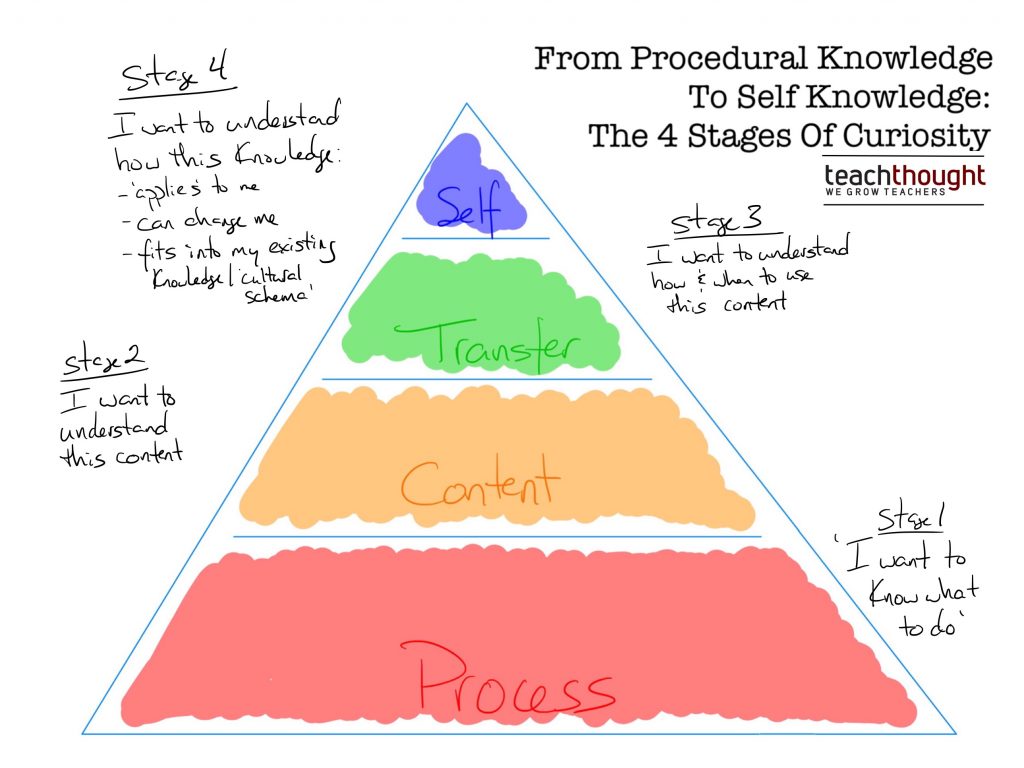

Curiosity and Change

In his Pensees (Thoughts), Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) remarked upon the transitions in history: Rivers are roads which move, and which carry us whither we desire to go. When we do not know the truth of a thing, it is of advantage that there should exist a common error which determines the mind of man, as,…

-

Painting in The Baroque Era | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

The most restrained baroque painter was probably Diego Velasquez (1599-1660), who spent thirty-four years at the court of Philip IV of Spain. Velasquez needed all his skill to soften the receding chins and large mouths of the Habsburgs and still make his portraits of Philip IV and the royal family instantly recognizable. His greatest feat…

-

The Baroque Era | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Baroque, the label usually applied to the arts of the seventeenth century. probably comes from the Portuguese barroco, “an irregular or misshapen pearl.” Some critics have seized upon the suggestion of deformity to criticize the impurity of seventeenth-century art in contrast with the purity of the Renaissance. Especially among Protestants, the reputation of baroque suffered…

-

Literature in the 17th Century | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Just as Henry IV, Richelieu, and Louis XIV brought greater order to French politics after the civil and religious upheavals of the sixteenth century, so the writers of the seventeenth century brought greater discipline to French writing after the Renaissance extravagance of a genius like Rabelais.

-

Progress and Pessimism in the 17th Century | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Scientists and rationalists helped greatly to establish in the minds of the educated throughout the West two complementary concepts that were to serve as the foundations of the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century: first, the concept of a “natural” order underlying the disorder and confusion of the universe as it appears to unrefleeting people in…

-

Century of Genius, Century of Everyman | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

In the seventeenth century the cultural, as well as the political, hegemony of Europe passed from Italy and Spain to Holland, France, and England. Especially in literature, the France of le grand siecle set the imprint of its classical style on the West through the writings of Corneille, Racine, Moliere, Bossuet, and a host of…

-

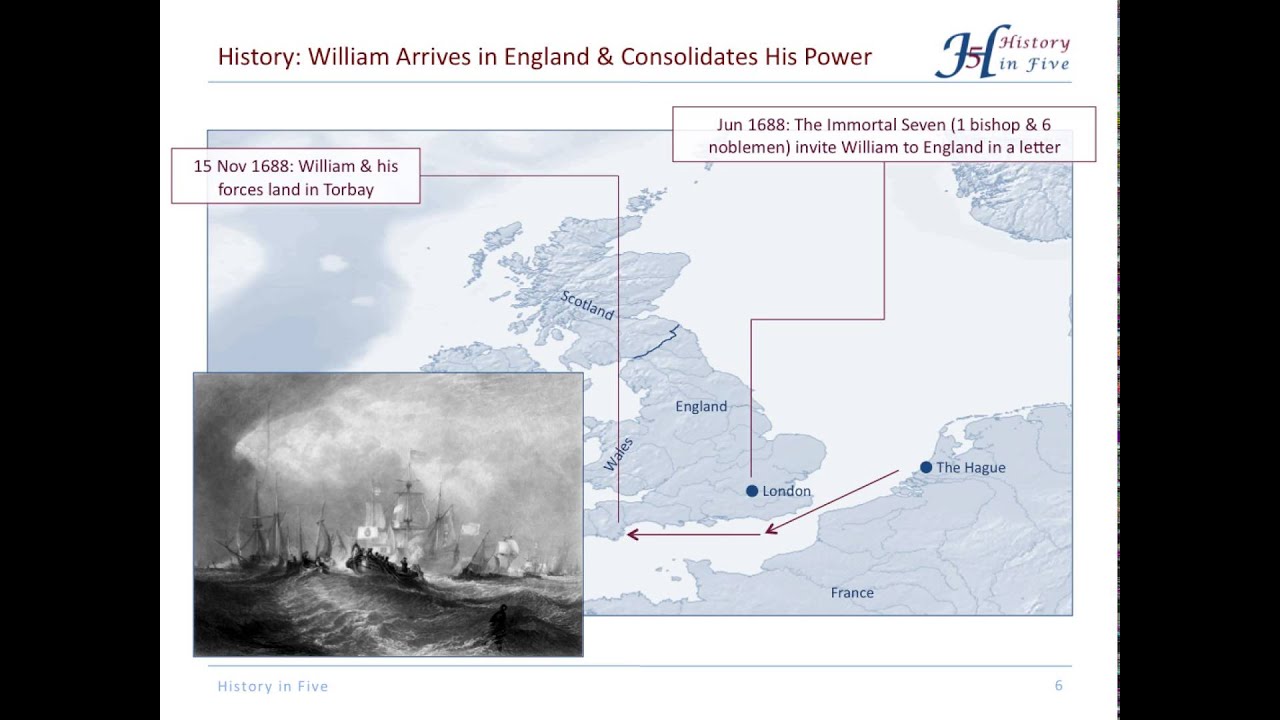

The Glorious Revolution and Its Aftermath, 1688-1714 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

The result was the Glorious Revolution, a coup d’etat engineered at first by a group of James’s parliamentary opponents who were called Whigs, in contrast to the Tories who tended to support at least some of the policies of the later Stuarts. The Whigs were the heirs of the moderates of the Long Parliament, and…

-

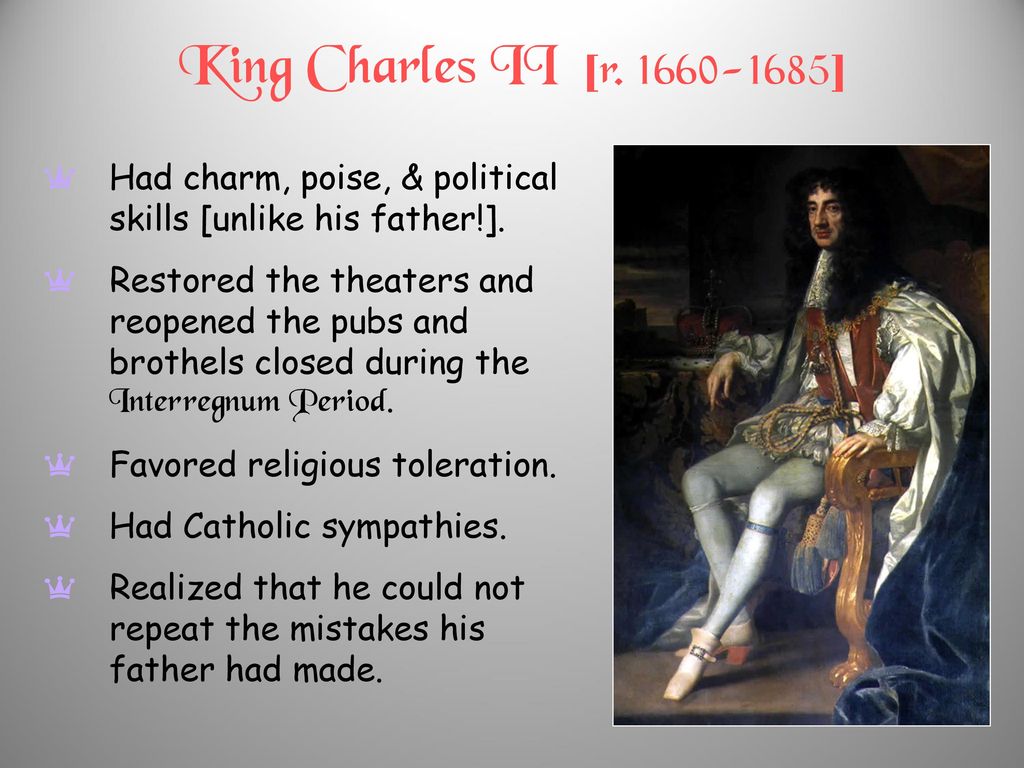

The Restoration, 1660-1688 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

The Restoration of 1660 left Parliament essentially supreme but attempted to undo some of the work of the Revolution. Anglicanism was restored in England and Ireland, though not as a state church in Scotland. Protestants who would not accept the Church of England were termed dissenters. Although they suffered many legal disabilities, dissenters remained numerous,…

-

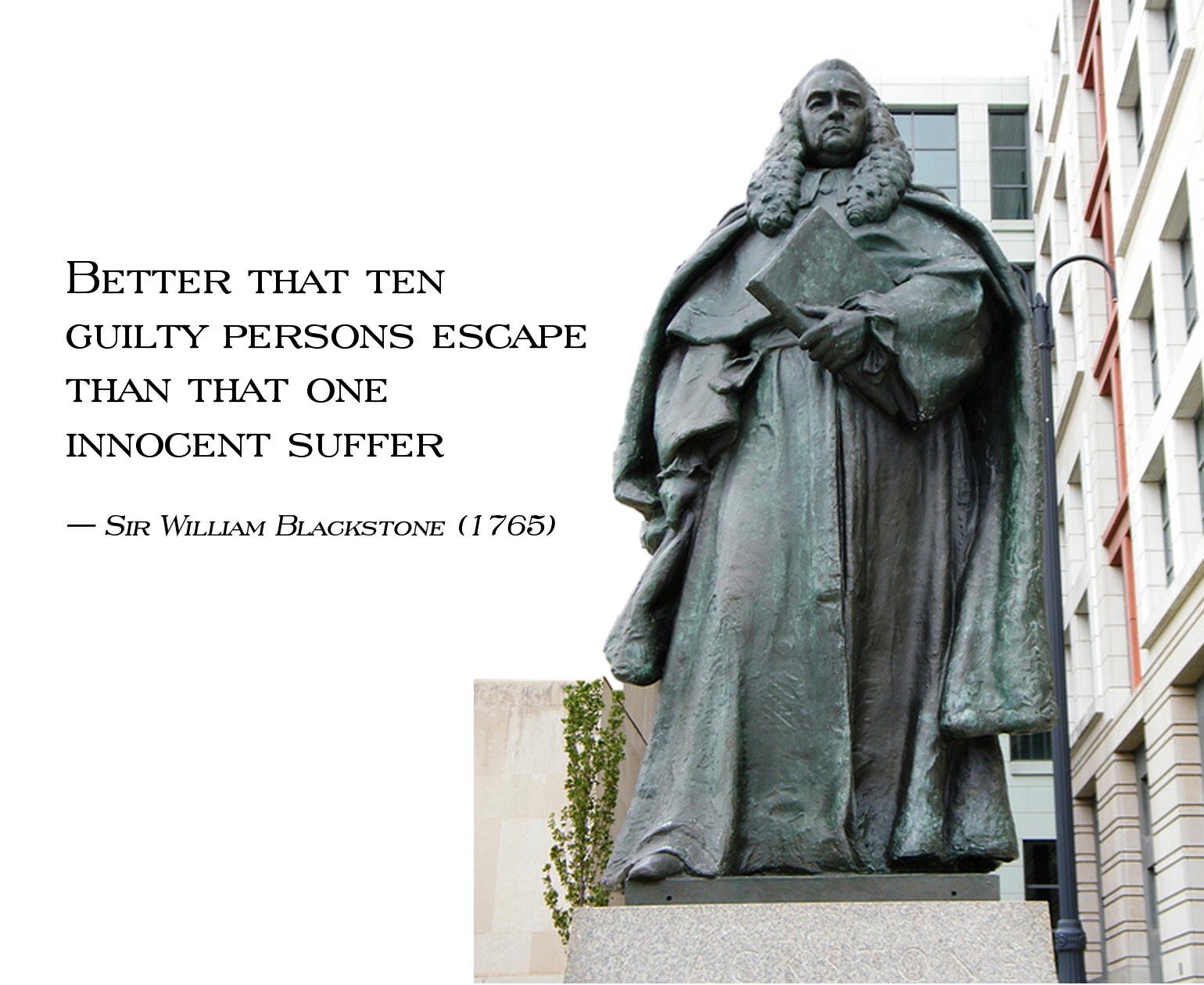

Blackstone on the Law

By the eighteenth century the English recognized that a unique constitution had evolved from the period of their Civil War. Basically unwritten, rooted in the common law, this constitution would contribute to a remarkable period of political stability. In 1765 an English jurist, William Blackstone (1723-1780), would prepare a lengthy set of commentaries on the…

-

The English Revolution in Review 1640-1660 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

At the height of their rule in the early 1650s some Puritans had attempted to enforce on the whole population the austere life of the Puritan ideal. This enforcement took the form of “blue laws”: prohibitions on horse racing, gambling, cock fighting, bear baiting, dancing on the greens, fancy dress, the theater, and a host…

-

Oliver Cromwell

Even today the character of Oliver Cromwell is the subject of much debate. Judgments on the English Civil War are shaped in some measure by opinions about Cromwell’s motives, actions, and policies. His supporters and detractors are no less firmly committed today than in Cromwell’s time, especially in Britain, where the role of the monarchy…

-

King Cromwell and the Interregnum, 1649-1660 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

The next eleven years are known as the Interregnum, the interval between two monarchical reigns. England was now a republic under a government known as the Commonwealth. Since the radicals did not dare to call a free election, which would almost certainly have gone against them, the Rump Parliament continued to sit.

-

The Civil War, 1642-1649 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

England was split along lines that were partly territorial, partly social and economic, and partly religious. Royalist strength lay largely in the north and west, relatively less urban and less prosperous than other parts, and largely controlled by gentry who were loyal to throne and altar. Parliamentary strength lay largely in the south and east,…

-

King Charles I, 1625-1642 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Under his son. Charles I, all James’s difficulties came to a head very quickly. England was involved in a minor war against Spain, and though the members of Parliament hated Spain, they were most reluctant to grant Charles funds to support the English forces. Meanwhile, despite his French queen, Charles became involved in a war…

-

King James I, 1603-1625 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

In the troubled reign of James I there were three major points of contention—money, foreign policy, and religion. In all three issues the Crown and its opposition each tried to direct constitutional development in its own favor. In raising money James sought to make the most of revenues that did not require a parliamentary grant;…

-

Stuart England | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

To the extent that English government utilized the new methods of professional administration developed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it was potentially as absolute as any divine-right monarchy. But the slow growth of representative government checked this potential, generating a set of rules not to be altered easily by the ordinary processes of government.

-

French Aggression in Review | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Proponents of the view that Europe underwent a severe crisis during the seventeenth century can find much evidence in the horrors resulting from Louis XIV’s aggressions. The total cost of his wars in human lives and economic resources was very great, especially in the deliberate French devastation of the German Palatinate during the War of…

-

The Last Two Wars of King Louis XIV | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

But in the last three decades of Louis’s reign most of his assets were consumed. Not content with the prestige he had won in his first two wars, Louis took on most of the Western world in what looked like an effort to destroy the independence of Holland and most of western Germany and to…

-

The First Two Wars of King Louis XIV | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

The main thrust of this vast effort was northeast, toward the Low Countries and Germany. Louis XIV sought also to secure Spain as a French satellite with a French ruler. Finally, French commitments overseas in North America and in India drove him to attempt, against English and Dutch rivals, to establish a great French empire…

-

French Expansion after The Thirty Years’ War

France was the real victor in the Thirty Years’ War, acquiring lands on its northeastern frontier. In a postscript to the main conflict, it continued fighting with Spain until the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659, securing additional territories. Prospering economically, France was ready for further expansion when the young and ambitious Louis XIV began…

-

Mercantilism and Colbert | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Divine-right monarchy was not peculiarly French, of course, nor was the mercantilism practiced by the France of Louis XIV. But like divine-right rule, mercantilism flourished most characteristically under the Sun King. Mercantilism was central to the early modern effort to construct strong, efficient political units.

-

The Royal Administration | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Of course, in a land as large and complex as France, even the tireless Louis could do no more than exercise general supervision. At Versailles he had three long conferences weekly with his ministers, who headed departments of war, finance, foreign affairs, and the interior.

-

Divine-Right Monarchy | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

The much admired and imitated French state, of which Versailles was the symbol and Louis XIV the embodiment, is also the best historical example of divine-right monarchy. Perhaps Louis never actually said, “Letat c’est moi” (I am the state), but the phrase clearly summarizes his convictions about his role. In theory, Louis was the representative…

-

Le Grand Monarque

At age twenty-two Louis XIV already displayed an impressive royal presence, as reported by Madame de Motteville (d. 1689), an experienced observer of the French court:

-

King Louis XIV, 1643-1714 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

When Mazarin died in 1661, Louis XIV began his personal rule. He had been badly frightened during the Fronde when rioters had broken into his bedroom, and he was determined to suppress any challenge to his authority, by persuasion and guile if possible, and by force if necessary. In 1660 he married a Spanish princess…

-

Jules Mazarin 1602-1661 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

The deaths of Richelieu in 1642 and Louis XIII in 1643, the accession of another child king, and the regency of the hated queen mother, Anne of Austria (actually a Habsburg from Spain, where the dynasty was called the house of Austria), all seemed to threaten a repetition of the crisis that had followed the…

-

Louis XIII and Richelieu, 1610-1643 | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

Louis was fortunate in securing the assistance of the remarkably talented duc de Richelieu (1585-1642), who was an efficient administrator as bishop of the remote diocese of Autun. Tiring of provincial life, Richelieu moved to Paris and showed unscrupulous skill in political maneuvering during the confused days of the regency.

-

Bourbon France | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

In 1610 the capable and popular Henry IV was assassinated in the prime of his career by a madman who was believed at the time to be working for the Jesuits—a charge for which there is no proof. The new king, Louis XIII (r. 1610-1643), was nine years old; the queen mother, Marie de Medici,…

-

The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

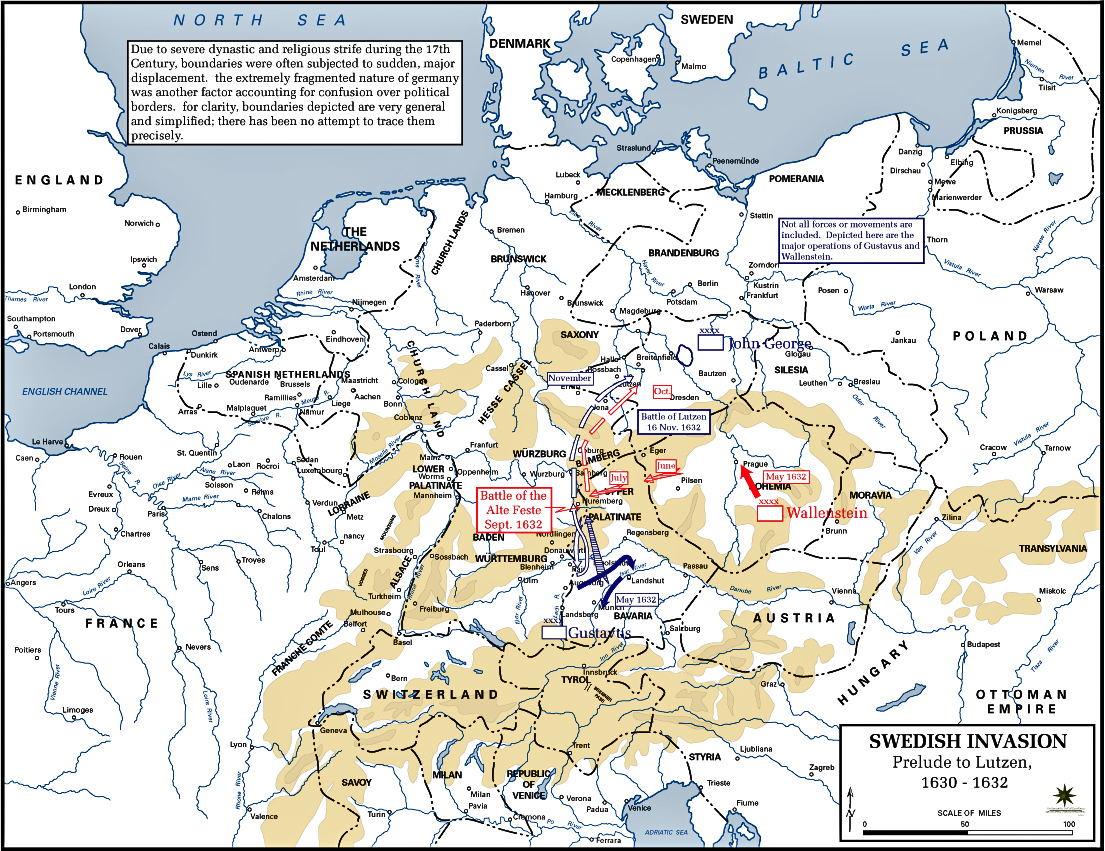

The peace of Westphalia in 1648 ended the Thirty Years’ War but also marked the end of an epoch in European history. It ended the Age of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, when wars were both religious and dynastic in motivation, and the chief threats to a stable international balance came from the Catholic Habsburgs and…

-

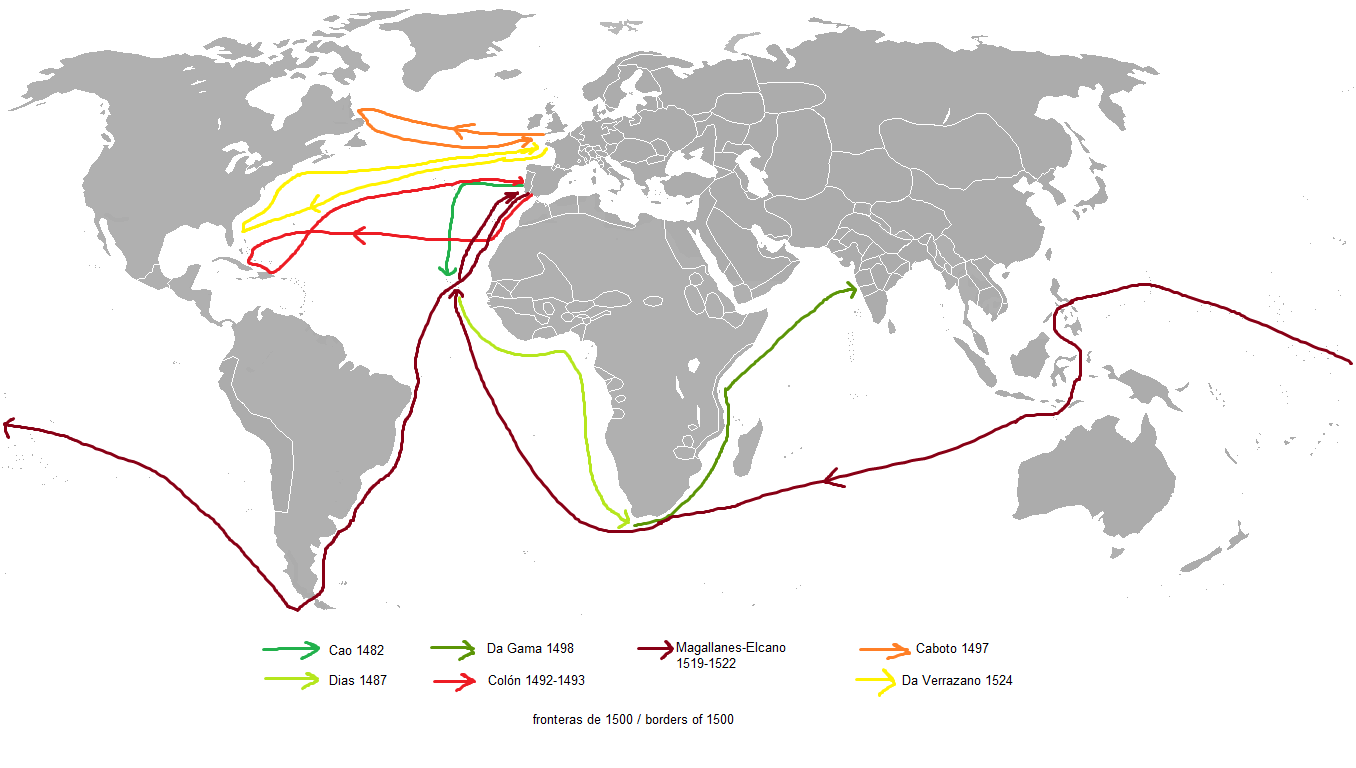

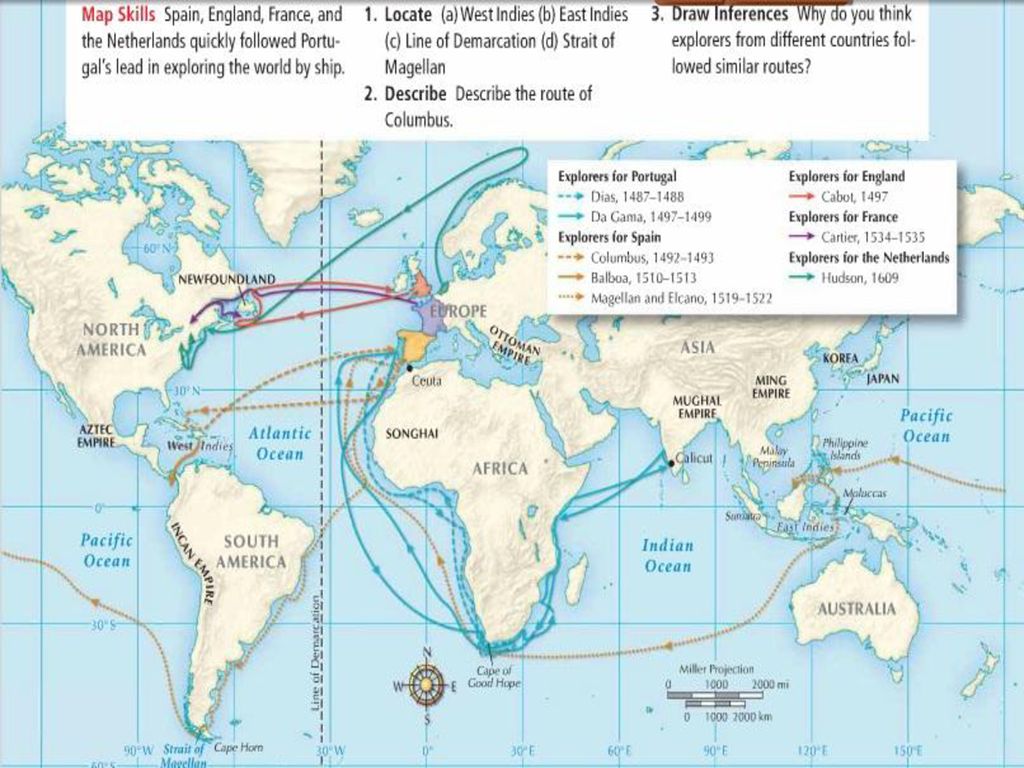

Summary | European Exploration and Expansion

In the early modern period explorers representing western European nations crossed vast oceans to discover other civilizations. With superior material and technological strength, especially firearms, Europeans were able to win empires. The motives for European expansion varied from desire to serve God, to glory, gold, and strategic need.

-

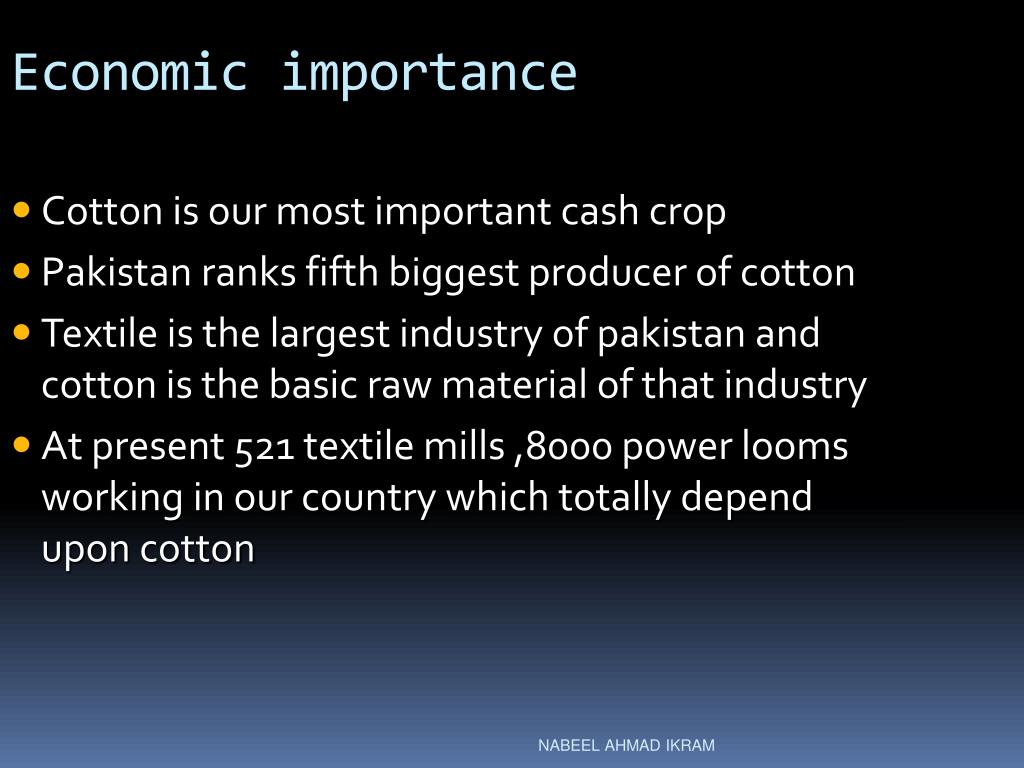

The Importance of Cotton

Cotton had been known from time immemorial in Egypt, India, and China; it was introduced into Spain in the ninth century, but it was hardly known in England until the fifteenth century. Only in the seventeenth century was it introduced extensively from India, and then into other “divers regions,” including the southern colonies of English…

-

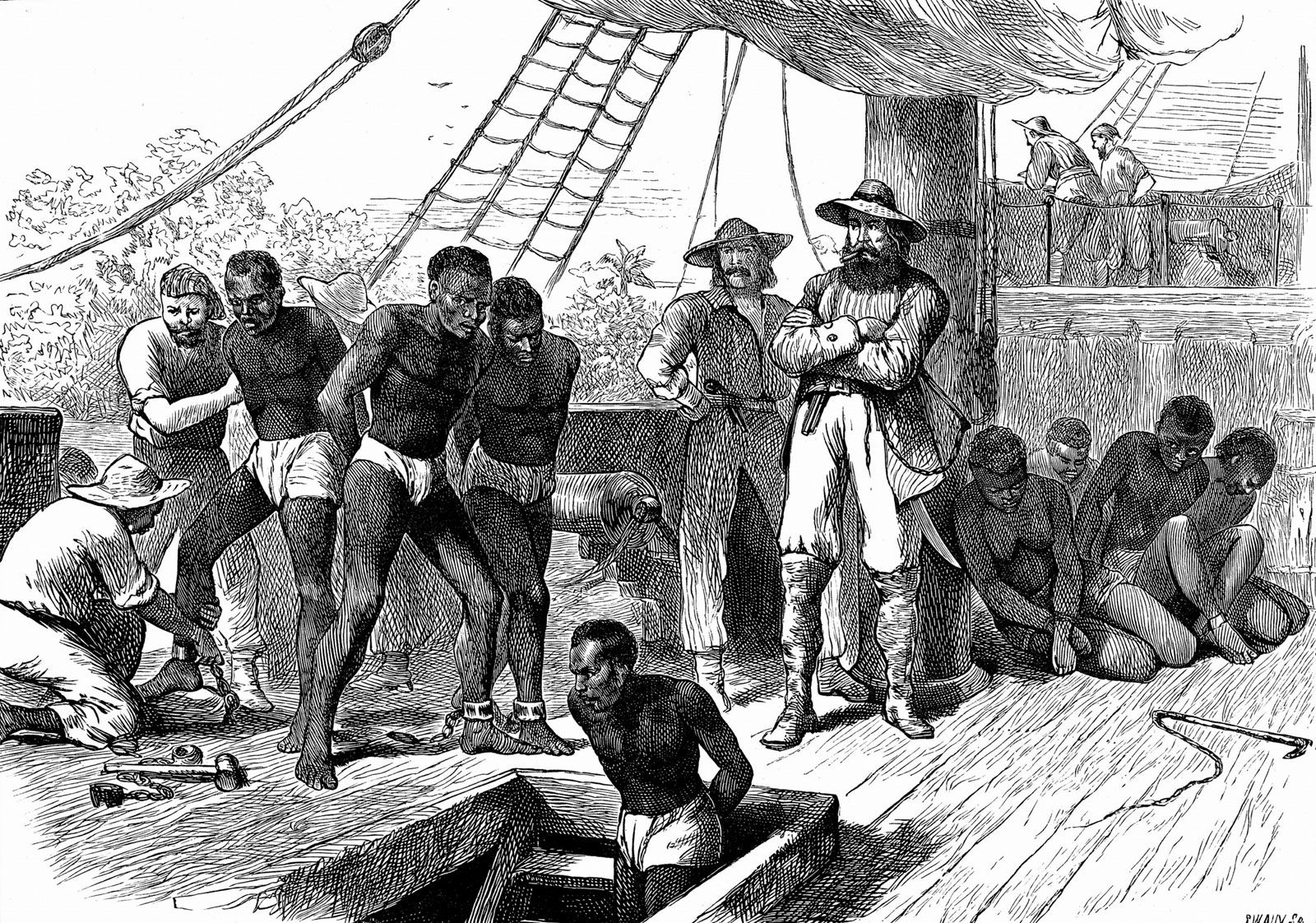

The Slave Trade

The Dutch slave ship St. Jan started off for Curacao in the West Indies in 1659. Its log recorded deaths of slaves aboard, until between June 30 and October 29 a total of 59 men, 47 women, and 4 children had died. They were still 95 slaves aboard when disaster struck, thus matter-of-factly recorded:

-

The Impact of Expansion | European Exploration and Expansion

The record of European expansion contains pages as grim as any in history. The African slave trade—begun by the Africans and the Arabs and turned into a profitable seaborne enterprise by the Portuguese, Dutch, and English—is a series of horrors, from the rounding up of the slaves by local chieftains in Africa, through their transportation…

-

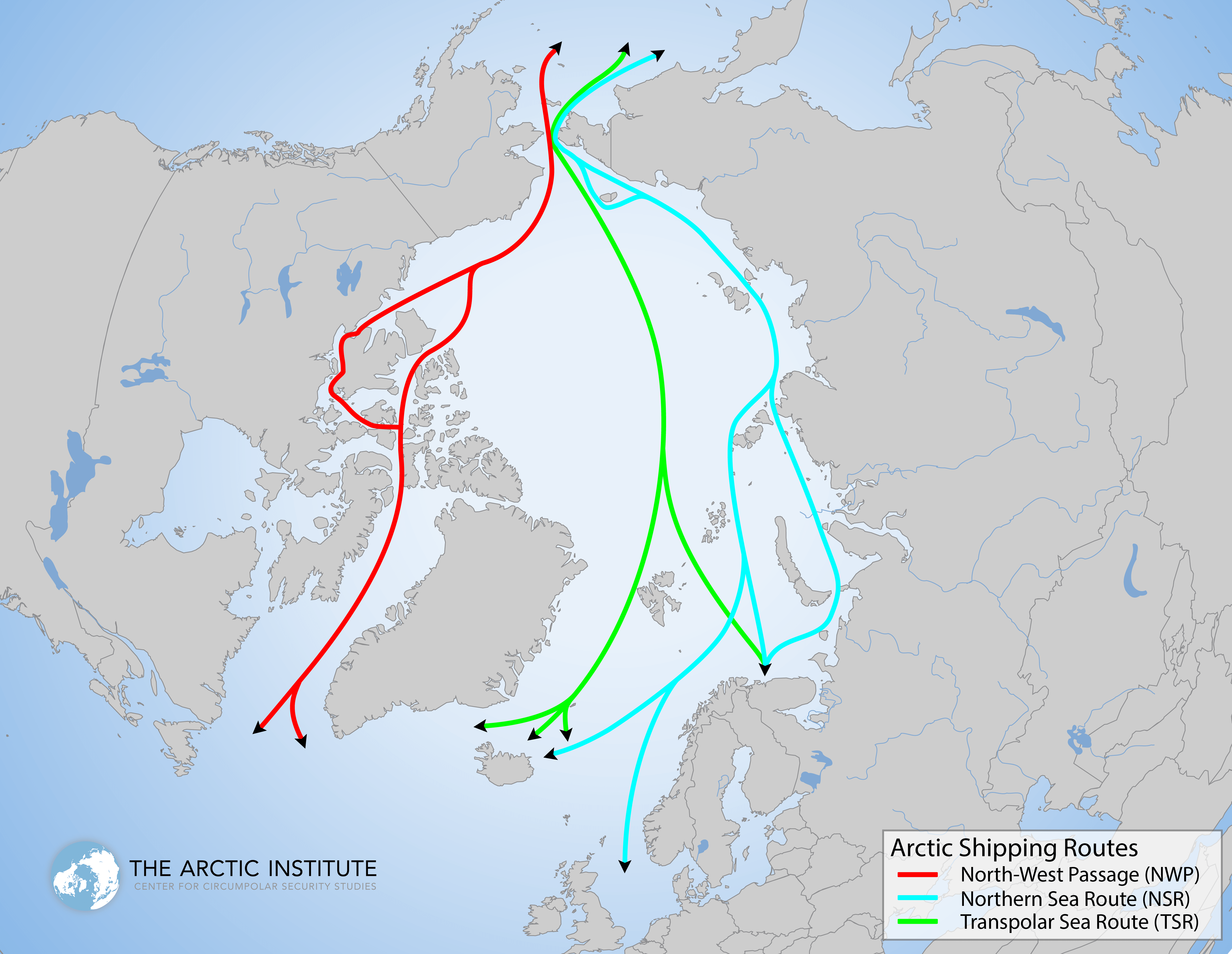

North by Sea to the Arctic | European Exploration and Expansion

Henry Hudson had found not only the Hudson River but also Hudson Bay in the far north of Canada. In 1670 English adventurers and investors formed the Hudson’s Bay Company, originally set up for fur trading along the great bay to the northwest of French Quebec. In the late sixteenth century the Dutch had penetrated…

-

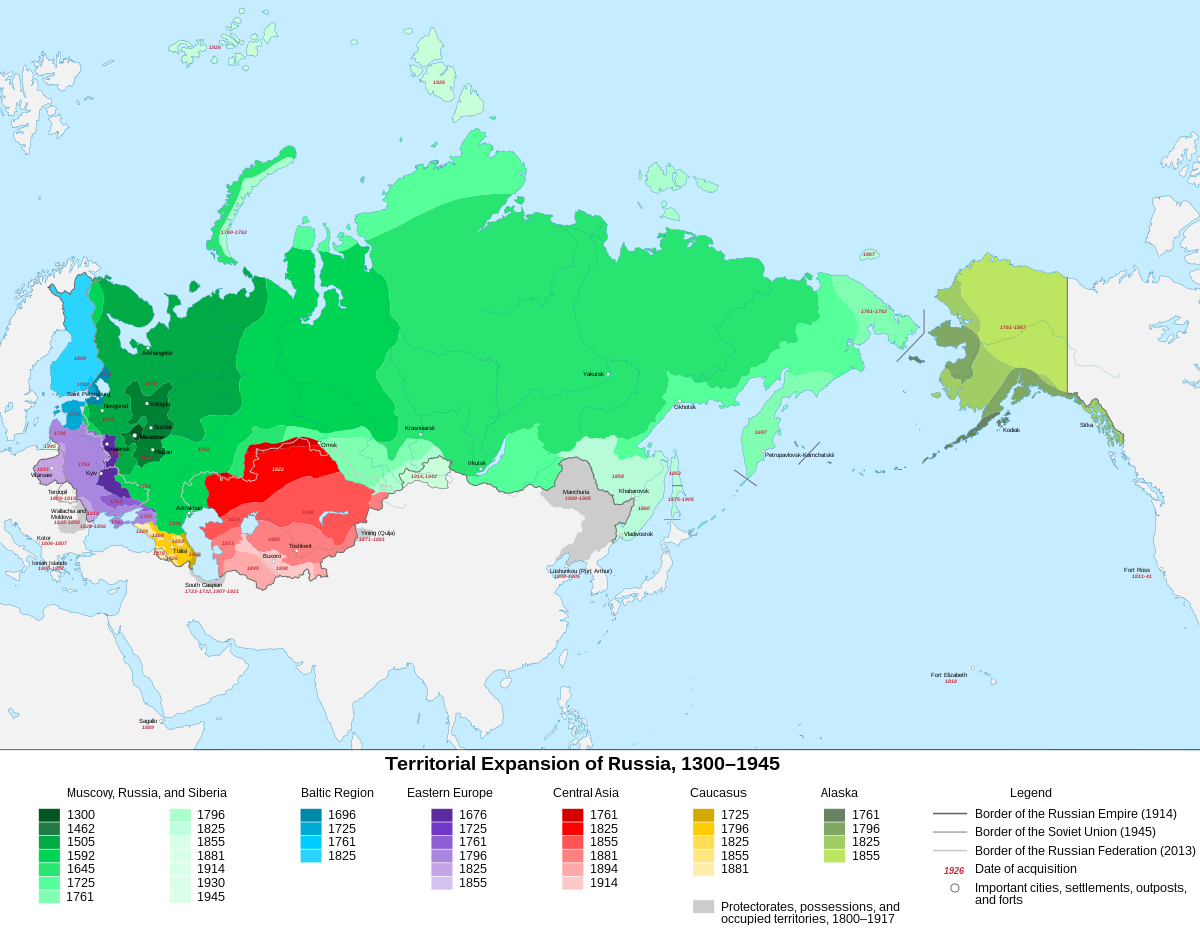

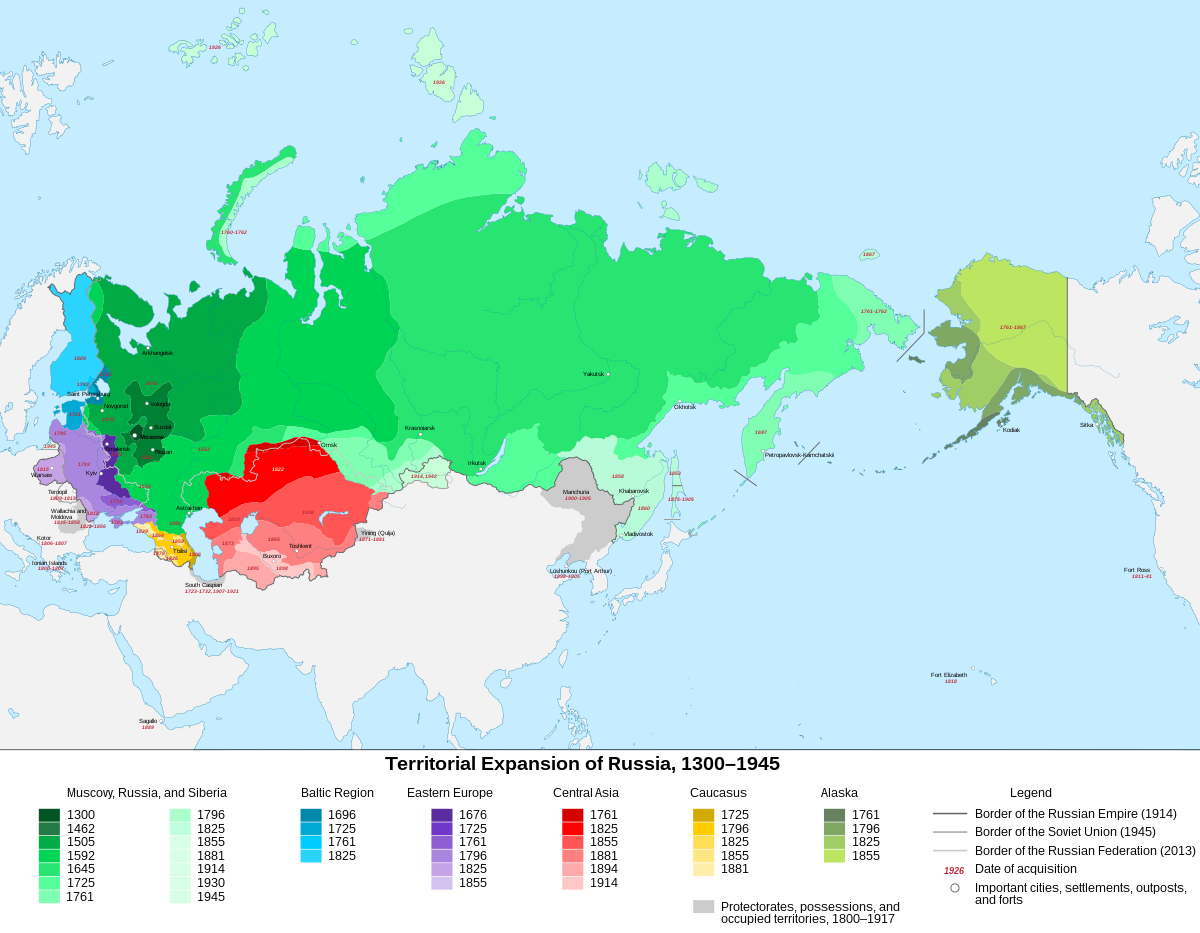

Russia: East by Land to the Pacific | European Exploration and Expansion

The victories of Ivan the Terrible over the Volga Tatars led to the first major advances, with private enterprise leading the way. By the end of the sixteenth century the Stroganov family had obtained huge concessions in the Ural area, where they made a great fortune in the fur trade and discovered and exploited Russia’s…

-

Russia | European Exploration and Expansion

Russian exploration and conquest of Siberia matched European expansion in the New World, both chronologically (the Russians crossed the Urals from Europe into Asia in 1483) and politically, for expanding Muscovite Russia was a “new” monarchy. This Russian movement across the land was remarkably rapid—some five thou¬sand miles in about forty years.

-

Africa and the Far East: Areas of Influence | European Exploration and Expansion

To reach the East all three of the northern maritime powers used the ocean route around Africa that the Portuguese had developed in the fifteenth century. All three secured African posts, with the Dutch occupying the strategic Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of the continent in 1652.

-

A Japanese Folk Tale

The age of exploration, discovery, and conquest was a two-way street, for the non-Western culture often reacted quickly and effectively to the arrival of Europeans. The following Japanese tale, a clever variant on the dictim that in the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king, suggests one form of interaction. Once upon a…

-

The Two Indies, West and East: Areas of Conquest | European Exploration and Expansion

The French, Dutch, and English all sought to gain footholds in South America, but had to settle for the unimportant Guianas. They thoroughly broke up the Spanish hold on the Caribbean, however. In early modern times these islands were one of the great prizes of imperialism. Cheap slave labor raised tobacco, fruits, coffee, and, most…

-

The French in North America | European Exploration and Expansion

To the north and west of the fourteen colonies, in the region of the St. Lawrence basin, the French built upon the work of Cartier and Champlain. The St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes gave the French easy access to the heart of the continent, in contrast to the Appalachian ranges that stood between…

-

English, Dutch, and Swedes in North America | European Exploration and Expansion

The English did not immediately follow up the work of the Cabots. Instead, they put their energies into breaking into the Spanish trading monopoly. In 1562 John Hawkins started the English slave trade; his nephew, Francis Drake, reached the Pacific and claimed California for England under the name of New Albion.

A History of Civilization