What we know of Muhammad is derived from Muslim authors who lived sometime after his death. The Arabia into which he was born about A.D. 570 was inhabited largely by nomadic tribes, each under its own chief. These nomads lived on the meat and milk of their animals and on dates from palm trees. They raided each other’s flocks of camels and sheep and often feuded among themselves.

The religion of the Arabs centered upon sacred stones and trees. Their chief center was Mecca, fifty miles inland from the coast of the Red Sea, where there was a sacred building called the Kaaba (the Cube), in which the Arab worshipers revered many idols, especially a small black stone “fallen from heaven,” perhaps a meteorite.

In the sixth century Mecca was inhabited by the Kuraish, a trading people who lived by caravan commerce with Syria. Muhammad was born into one of the clans of the Kuraish. Orphaned early, he was brought up by relatives and as a young man entered the service of a wealthy widow older than himself, whom he later married. We do not know how he became convinced that he was the bearer of a new revelation.

Muhammad was keenly aware of the intense struggle going on between the two superpowers, Byzantium and Persia. News of the shifting fortunes of war reached him, and he apparently sympathized with the Christians, and perhaps even thought of himself as destined to lead a reform movement within Christianity. He seems to have spent much time in fasting and vigils, perhaps suggested by Christian practice. He became convinced that God was revealing the truth to him and had singled him out to be his messenger; these revelations came to him gradually over the rest of his life, often when some crisis arose.

The whole body of revelation was not assembled in the Koran until after Muhammad’s death. The chapters were not arranged in order by subject matter, but mechanically by length, with the longest first, which makes the Koran difficult to follow. Moreover, it is full of allusions to things and persons not called by their right names. Readers are often puzzled by the Koran, and a large body of Muslim writings explaining and debating it has grown up over the centuries.

is the god of the Jews and Christians, yet Muhammad did not deny that his pagan fellow Arabs also had knowledge of god. He declared that it was idolatry to worship more than one god, and he believed the trinity of the Christians to be three gods and therefore polytheism. If Judaism emphasizes God’s justice and Christianity his mercy, Islam may be said to emphasize his omnipotence. Acknowledgment of belief in God and in Muhammad as the ultimate prophet of God and acceptance of a final day of judgment are the basic requirements of the faith. A major innovation for the Arabs was Muhammad’s idea of an afterlife, which was to be experienced in the flesh.

The formal demands of Islam were not severe. Five times a day in prayer, facing toward Mecca, the Muslim, having first washed face, hands, and feet, would bear witness that there is no god but Allah and that Muhammad is his prophet. During the sacred month of Ramadan, Muslims may not eat, drink, or have sexual relations between sunrise and sunset. They must give alms to the poor, and, if they can, they should at least once in their lifetime make a pilgrimage (the haji) to the sacred city of Mecca. Polygamy was sanctioned, but four wives were the most a man, save the Prophet himself, could have. Divorce was easy for the husband, who needed only to repeat a prescribed formula.

Historians note many similarities between Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. All are monotheistic, and all worship the same God, using different language. Muslims worship together but do not require an organized church to attend: individual prayer is at the heart of expressing faith. Jews, too, worship together but require no formal church. Muslims and Christians both believe in the Last Judgment. To Muslims, Jews and Christians were “people of the Book,” that is, people who worshiped through a holy scripture.

Allah’s message also appeared in a text, the Koran or, in Arabic, Qur’an, but it did not represent a series of commandments so much as a guide to living in such a way as to achieve salvation. The Qur’an describes the tortures of the damned at the Last Judgment, as did Christian texts and illustrations, but the vision of the rewards of the saved differed: to the Muslim, heaven was a place of running water and green parks and gardens, and the saved would retain their riches, dressing handsomely and eating well in the company of physical beauty.

At first Muhammad preached this faith only to members of his family; then he preached to the people of Mecca, who repudiated him scornfully. In 622 some pilgrims from a city called Yathrib, two hundred miles north of Mecca, invited Muhammad to come to their city to settle a local war. He accepted the invitation. This move from Mecca is the Hegira (flight), from which the Islamic calendar has ever since been dated. Thus the Christian year 622 is the Muslim year 1. Yathrib had its name changed to al-Medina, the city. Medina became the center of the new faith, which grew and prospered.

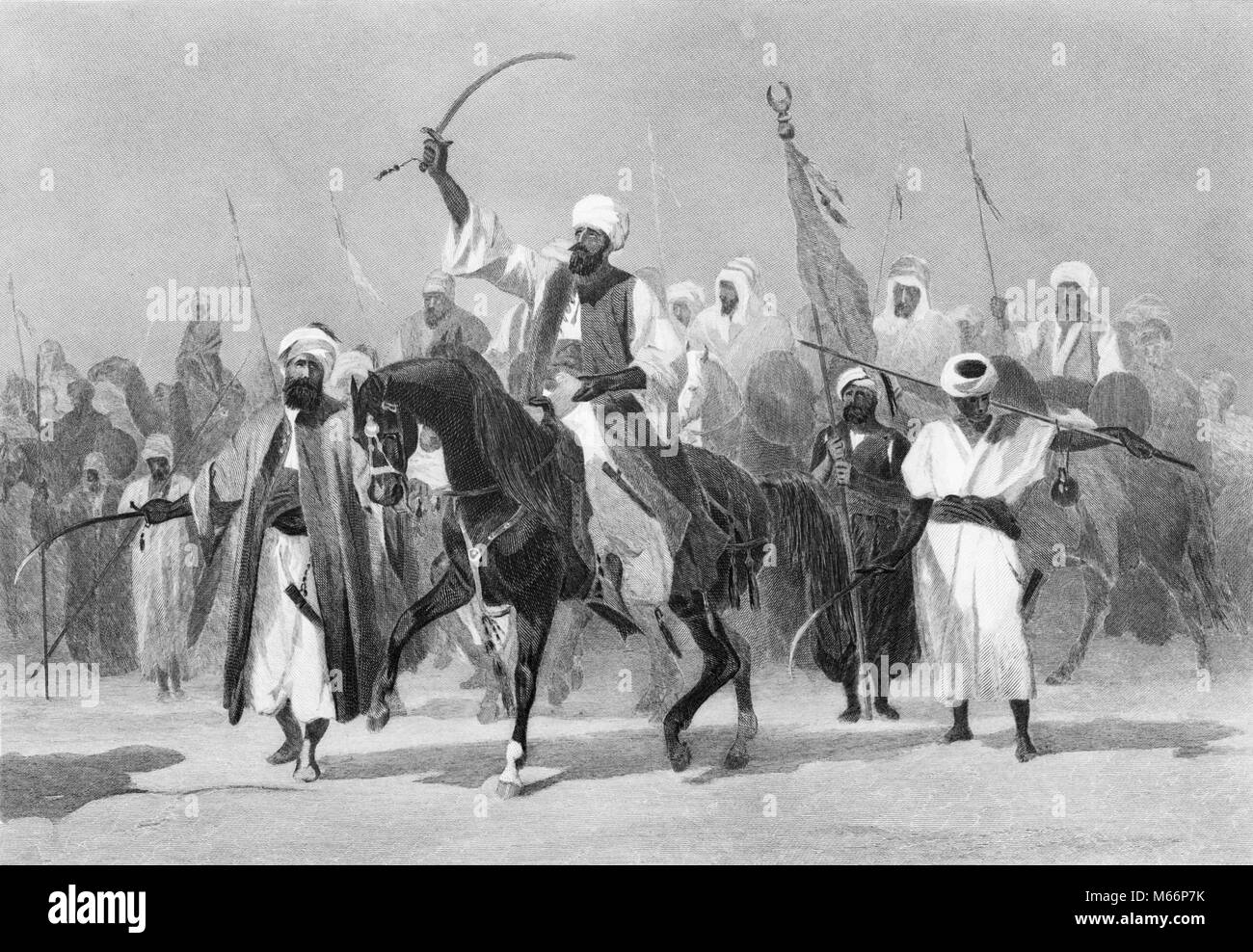

When the Jews of Medina did not convert, Muhammad came to depend more upon the Arabs of the desert and became less universal in his appeal. Allah told him to fight against those who had not been converted. The holy war (jihad) is a concept very like the Christian Crusade; those who die in battle against the infidel die in a holy cause. After Heraclius defeated the Persians, Muhammad returned in triumph to Mecca in 630. He cleansed the Kaaba of all idols, retaining only the black stone, and he made it a shrine of his new religion. Two years later, in 632, Muhammad died.