Ultimately more significant was the Dardanelles campaign of 1915. With the entry of Turkey into the war on the side of the Central Powers in November 1914, and with the French able to hold the western front against the Germans, a group of British leaders decided that British strength should be put into amphibious operations in the Aegean area, where a strong drive could knock Turkey out of the war by the capture of Constantinople.

The great exponent of this eastern plan was Winston Churchill, first lord of the admiralty. The point of attack chosen was the Dardanelles, the more southwesterly of the two straits that separate the Black Sea from the Aegean. The action is known as the Gallipoli campaign for the long, narrow peninsula on the European side of the Dardanelles that was a key to the action.

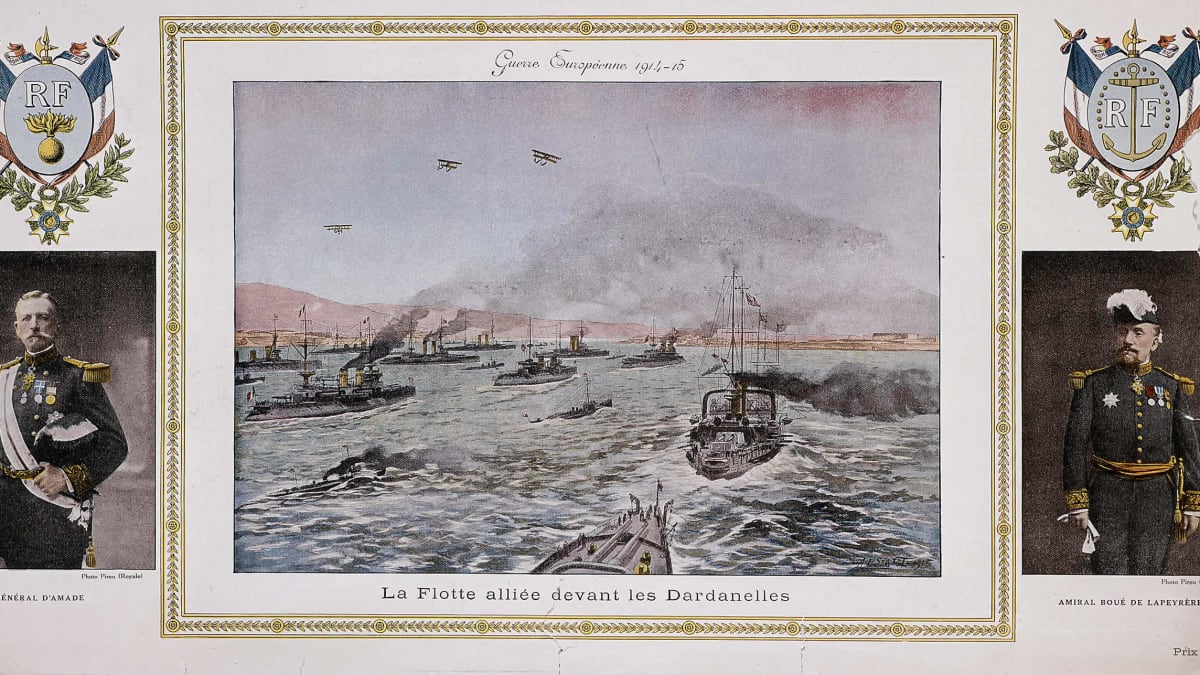

The British and French fleets tried to force the Straits in March 1915, but they abandoned the attempt when several ships struck mines. Later landings of British, Australian, New Zealand, and French troops at various points on both the Asian and European shores of the Dardanelles were poorly coordinated and badly backed up. They met fierce and effective resistance from the Turks, and in the end they had to withdraw without taking the Straits. The cost of this campaign was enormous: 500,000 casualties. The Anzac (Australian and New Zealand) troops felt they had been led into sense- less slaughter by British officers, and a sense of a separate Australian nationalism was clearly expressed for the first time.

Serbia’s part in the crisis that had produced the war meant that from the start there would be a Balkan front. In the end all Balkan states became involved. The Austrians failed here also, and although they managed to take the Serbian capital, Belgrade (December 1914), they were driven out again. Bulgaria, wooed by both sides, finally came in with the Central Powers in the autumn of 1915. The Germans sent troops and a general, August von Mackensen (1849-1938), under whom the Serbs were finally beaten.

To counter this blow in the Balkans, the British and French had already landed a few divisions in the Greek city of Salonika and had established a front in Macedonia. The Greeks themselves were divided into two groups. One was headed by King Constantine (1868-1923), who sympathized with the Central Powers but who for the moment was seeking only to maintain Greek neutrality.

The other was a pro-Ally group headed by the able prime minister Eleutherios Venizelos (1864-1936), who had secretly agreed to the Allied landing at Salonika. Venizelos did not get firmly into the saddle until June 1917, when Allied pressure compelled King Constantine to abdicate in favor of his second son, Alexander (1893-1920). Greece then declared war on the Central Powers.

Meanwhile Romania, which the Russians had been trying to lure into the war, yielded to promises of great territorial gains at the expense of Austria-Hungary; Romania came in on the Allied side in August 1916. The Central Powers swept through Romania and by January 1917 held most of the country. When the Russians made the separate Peace of Brest-Litovsk with the Germans in March 1918, the Romanians were obliged to yield some territory to Bulgaria and to grant a lease of oil lands to Germany.

The Macedonian front remained in a stalemate until the summer of 1918. Then, with American troops pouring rapidly into France, the Allied military leaders decided they could afford to build up their forces in Salonika. The investment paid well, for under the leadership of the French general Franchet d’Esperey (1856— 1942), the Allied armies on this front were the first to break the enemy completely.

The French, British, Serbs, and Greeks began a great advance in September all along a line from the Adriatic to the Bulgarian frontier. They forced the Bulgarians to conclude an armistice on September 30, and by early November they had crossed the Danube in several places. The armistice in the West on November 11 found the tricolor of France, with the flags of many allies, well on its way to Vienna.