From 1849 until his death in 1883, Marx lived in London, where, partly because of his own financial mismanagement, his family experienced the misery of a proletarian existence in the slums of Soho.

After poverty and near-starvation had caused the death of three of his children, he eventually obtained a modest income through the generosity of Engels and from his own writings. Throughout this time he revised his writings, setting out his main principles in the Grundrisse and then departing from the outline thus completed in 1858 to write the first volume of Das Kapital in 1867. Two further volumes of Das Kapital, pieced together from his notes, were published after his death.

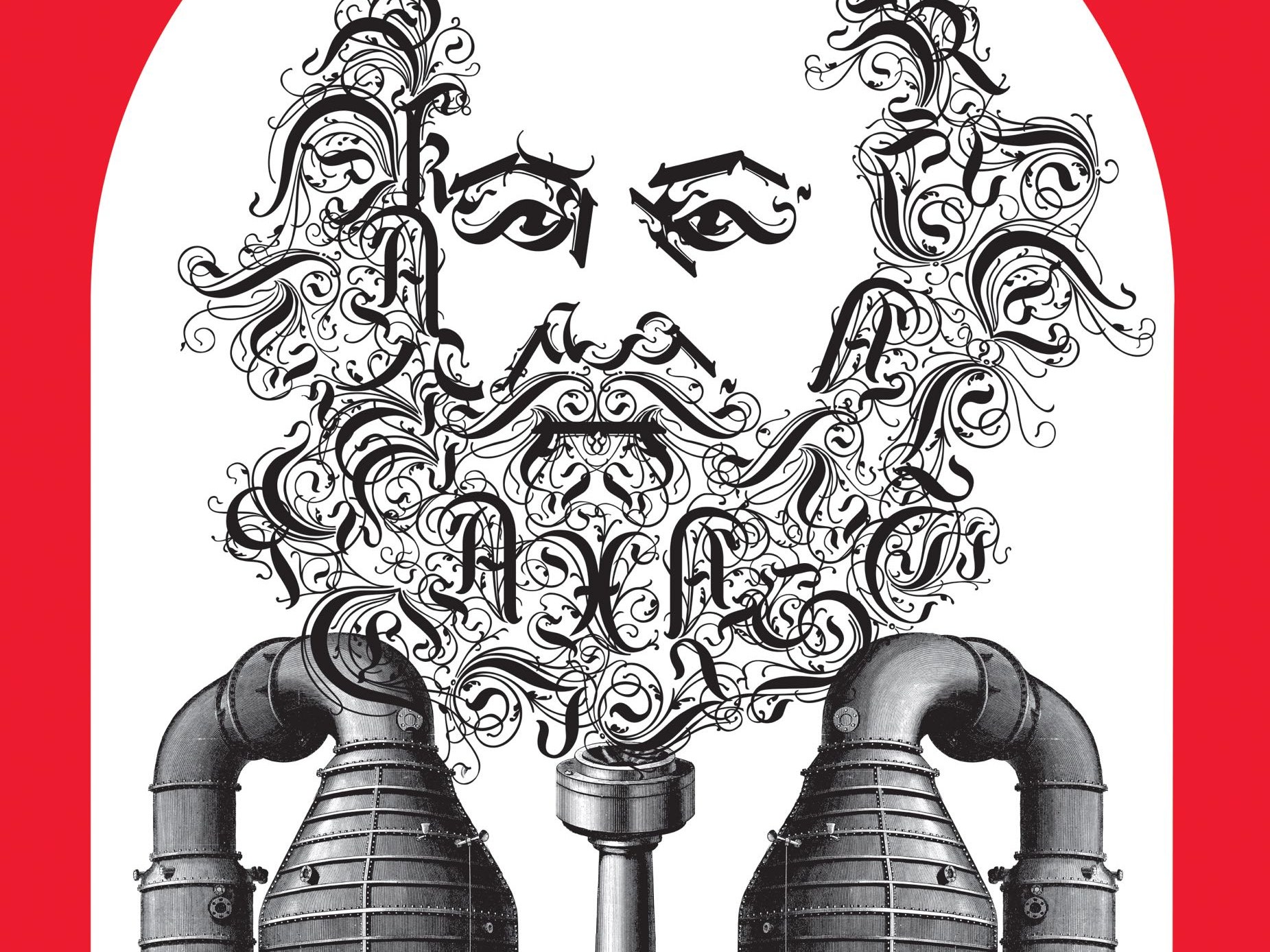

In Das Kapital Marx spelled out the labor theory of value according to which the workers created the total value of the commodity that they produced, yet received in the form of wages only a small part of the price for the item. The difference between the sale price and the workers’ wages constituted surplus value, something actually created by labor but appropriated by capital as profit. It was the nature of capitalism, Marx argued, to diminish its own profits by replacing human labor with machines and thus gradually choke off the source of surplus value. Thus would arise a mounting crisis of overproduction and underconsumption.

In 1864, three years before the first volume of Das Kapital was published, Marx joined in the formation of the First International Workingmen’s Association. This was an ambitious attempt to organize workers of every country and variety of radical belief. A loose federation rather than a coherent political party, the First International soon began to disintegrate; it expired in 1876. Increasing persecution by hostile governments helped to bring on its end, but so, too, did the factional quarrels that repeatedly engaged its members.

In 1889 a Second International was organized; it lasted until World War I and the Bolshevik revolution in Russia. The Second International represented the Marxian Socialist or Social Democratic parties, which were becoming important forces in the major countries of Continental Europe.

Among its leaders were men and women more politically adept than Marx. Yet factionalism continued to weaken the International. Some of its leaders tenaciously defended the precepts of the master and forbade any cooperation between socialists and the bourgeois political parties; these were the orthodox Marxists. Other leaders of the Second International revised his doctrines in the direction of moderation and of harmonization with the views of the Utopians.

These “revisionists” believed in cooperation between classes rather than in a struggle to the death, and they hoped that human decency and intelligence, working through the machinery of democratic government, could avert outright class war.

Both orthodox and heretical Marxists have persisted to the present day, with the orthodox view itself fragmenting, and the heretical views proliferating, as theoreticians and political leaders in Asia, Africa, and Latin America attempted, especially after World War II, to adapt Marxian analysis to the perceived realities of their situations.

Marx’s views would be significantly added to by V. I. Lenin, so that scholars prefer to speak of Marxism-Leninism when referring to the practices of the principal modern advocate of orthodoxy, the former Soviet Union.