In 359 B.C., a prince of the ruling house, Philip, became regent for his infant nephew. Having lived for three years as a hostage in Thebes, Philip understood Greek affairs. He applied Theban military principles to his army and led it in person. After defeating the Illyrians and other rivals for power within Macedon, Philip was made king in his own right.

Some Athenian politicians favored Philip’s advance. Others opposed him. It was not until he had won still more territory and begun to use a fleet successfully that the Athenian orator Demosthenes began to warn against the threat from Macedon. But Philip had broken Athenian influence in Thessaly and Thrace and had annexed the peninsula of Chalcidice. He also detached the large island of Euboea, close to Attica itself, from its Athenian loyalties.

At that point he suggested peace and an alliance with Athens. In 346 B.C. this was accomplished with the approval even of Demosthenes. Philip meanwhile had secured control over the Delphic oracle. He was moving south and consolidating his power. He made a temporary alliance with Thebes to defeat Phocis. By 342 the Athenians had acquired new allies in the Peloponnesus. In retaliation Philip moved into Thrace to cut off the Athenian grain supplies coming from the Black Sea and to avert a new Persian-Athenian alliance. Once again Demosthenes pressed for war, and Athens took military action in Euboea. By late 339 Philip was only two days’ march from Attica. Demosthenes now arranged an eleventh-hour alliance with Thebes. Philip, however, totally defeated the Athenian-Theban alliance at Chaeronea in 338 with the decisive aid of a precisely timed cavalry charge led by his eighteen-year-old son, Alexander. Though Philip occupied Thebes, he spared Athens on condition that the city ally with Macedon.

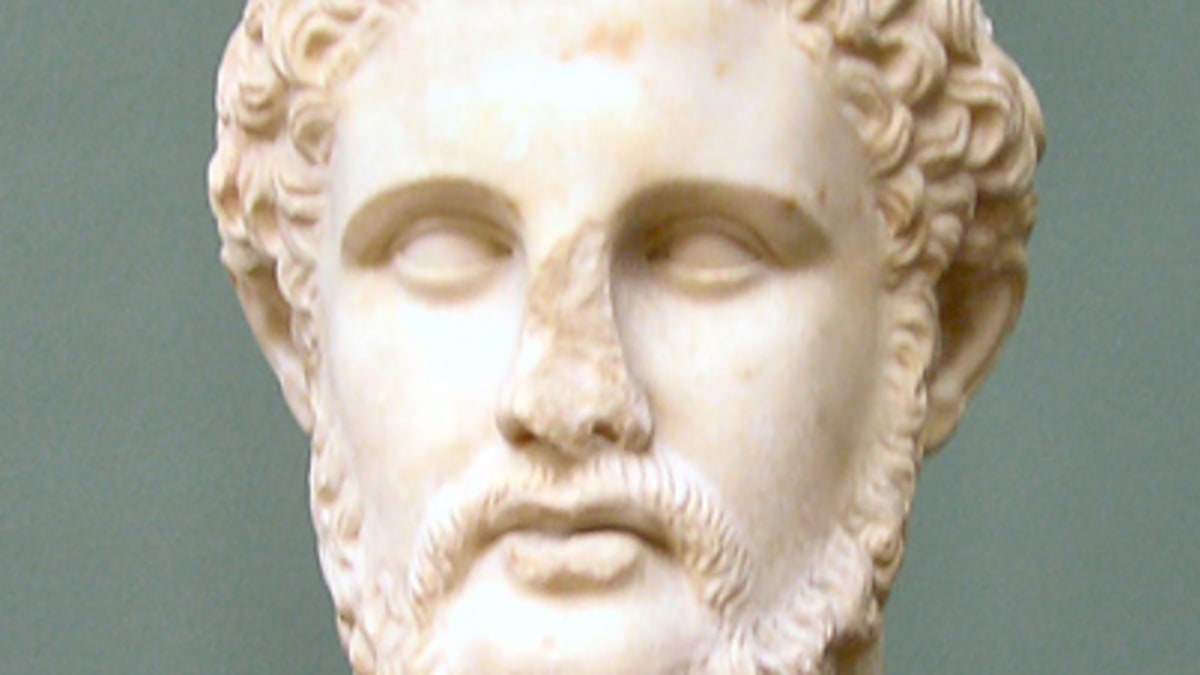

Philip’s victories aroused in many the old hope of a unified Greece. At Corinth in 338 B.C., all the poleis except Sparta met to organize a league that called itself “The Greeks.” Its members bound themselves to stop fighting and intervening in each other’s affairs. This body immediately allied itself with Macedon and then joined with Philip in declaring war on Persia to revenge Xerxes’ invasion of 143 years earlier. Philip was to command the expedition. By 336 B.C. the advance forces of this army were already liberating Ionian cities from Persia. But Philip, aged only forty-six, was now mysteriously assassinated.

Philip’s accomplishments greatly impressed his contemporaries. Instead of allowing the resources of Macedon to be dissipated in flashy conquests, he organized the people he conquered, both in the Balkan area from the Adriatic to the Black Sea and in Greece. He kept morale high in the army and had the contingents from the various regions competing to see who would do the best job. He divided his troops into specialized units for diverse tasks in war, and he personally commanded whichever unit had the most difficult assignment. He could appreciate the strengths of his Greek opponents, and when he had defeated them, he utilized their skills and made sure of their loyalty by decent treatment. In his final effort to unify them against their traditional Persian enemy, he associated himself with the ancient patriotic cause that, despite frequent disappointment, still had great appeal for them.