Twentieth-century writers surprised the prophets of doom. Poetry remained, for the most part, what it had become in the late nineteenth century: difficult, cerebral, and addressed to a small audience.

An occasional poet broke from the privacy of limited editions to wide popularity; representative was the attention given to T. S. Eliot (1888-1965). His difficult yet moving symbolic poem, “The Waste Land,” or his invocation to “The Hollow Men,” which closed with the lines

This is the way the world ends Not with a bang but a whimper

captured for a whole generation its sense of quiet despair, its anguish hidden in boredom, and its expectation of a cleansing flame to purge society.

However, the novel remained the most important form of contemporary imaginative writing. Although no one could predict which novelists of our century would be read in the twenty-first century, the American William Faulkner (1897-1962), the German Thomas Mann (1875– 1955), and the Frenchman Albert Camus (1913-1960) were already enshrined as classics.

Mann, who began with a traditionally realistic novel of life in his birthplace, the old Hanseatic town of Laibeck, never really belonged to the avant-garde. He was typical of the sensitive, worried, class-conscious artist of the age of psychology. Camus, too, was sensitive and worried, but with an existentialist concern in his novels and plays over human isolation and the need to engage oneself in life.

The most innovative novelist of the twentieth century surely was the Irishman James Joyce (1882-1941). Joyce began with a subtle, outspoken, but conventional series of sketches of life in the Dublin of his youth, Dubliners (1914), and an undisguised autobiography, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916).

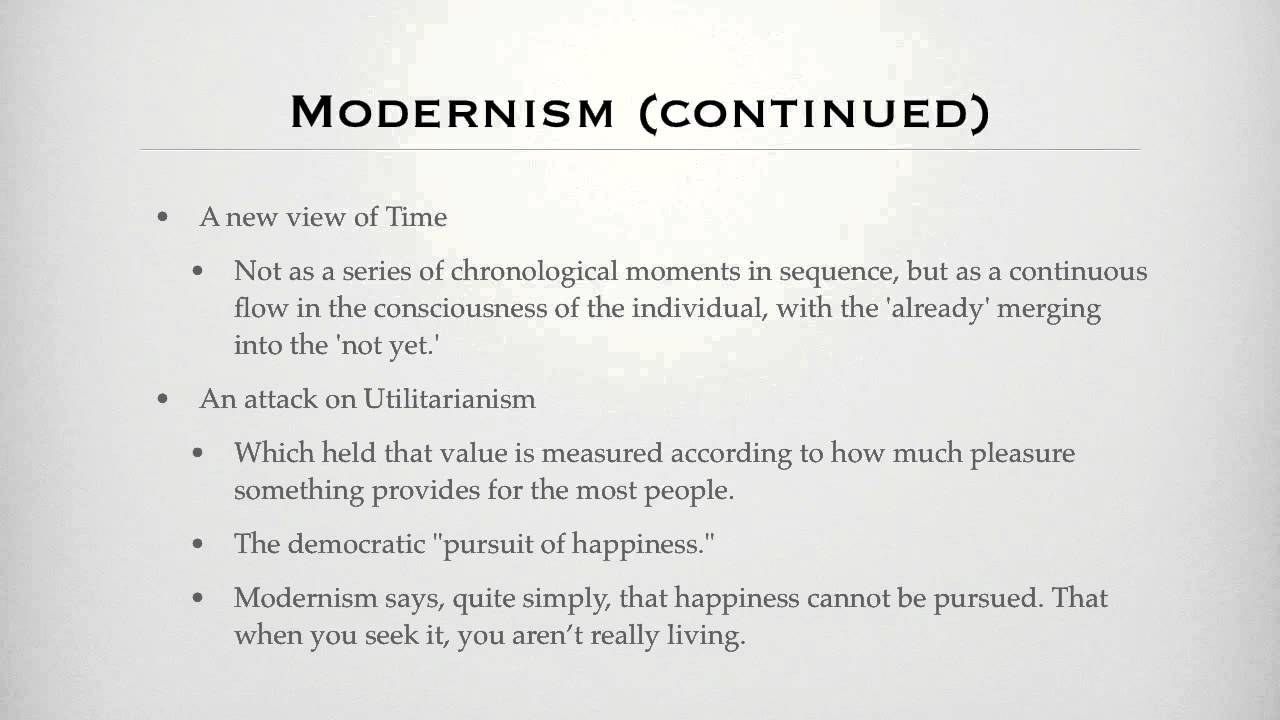

Then, in exile on the Continent, he wrote a classic experimental novel, Ulysses (1922), an account of twenty-four hours in the life of Leopold Bloom, a Dublin Jew. Ulysses is full of difficult allusions, parallels with Homer, puns, rapidly shifting scenes and episodes, and it is written without regard for the conventional notions of plot and orderly development. Above all, it makes full use of the recently developed psychology of the unconscious, as displayed in the stream of consciousness.

The last chapter, printed entirely without punctuation marks, is the record of what went on in the mind of Bloom’s wife, Molly, as she lay in bed waiting for him to come home. What went on in her mind was too shocking for most contemporaries, and Ulysses, published in Paris, had to be smuggled into English-speaking countries. The later widespread popularity of Joyce indicated the extent to which sexual mores and attitudes toward explicit language changed after World War II.

Postwar literature was explosive, diverse, and ever-growing. World War II released non-Western writers to publish widely in Europe and the Americas, so that figures previously known only in their own countries gained world renown. A growing permissiveness led to more and more realistic, as well as increasingly vulgar, forms of expression.

The novel, and in particular novels consciously written to be best sellers, came to dominate the marketplace. Vastly increased literacy led to vastly increased sales, to the point that a popular writer like the English mystery novelist Agatha Christie (1890-1976) came to outsell all but the Bible and to be translated into eighty languages. Fictional heroes such as Sherlock Holmes, the creation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), came to be treated by millions as though they were real figures.

The rise of a vast reading public that found writers like Eliot and Joyce too difficult, or simply not sufficiently entertaining, would have profound effects on education, literature, and society as a whole. Further, by the 1980s English had clearly replaced French as the language of diplomacy, German as the language of science, and all others as the major world language of commerce.