India was the richest of Britain’s overseas possessions, the center and symbol of empire, as the imaginative Disraeli realized when in 1876 he had Queen Victoria proclaimed empress of India.

It was over India that the British most often debated the merits of direct intervention versus indirect control, massive social reform imposed from without versus creation of a collaborating elite that would carry out the reforms from within, and whether nature (that is, race) or nurture (that is, environment) most determined a people’s future.

In 1763 India was not a single nation but a vast collection of identities and religions. As the nineteenth century began, the two main methods of British control had already become clear. The richest and most densely populated regions, centering on the cities of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay and on the Punjab, were maintained under direct British rule. The British government did not originally annex these lands; they were first administered by the English East India Company.

The company in its heyday had taken on enormous territories and made treaties like a sovereign power. In 1857 the company’s native army of Sepoys rebelled; the soldiers had come to fear that British ways were being imposed on them, to the destruction of their own ways. The Sepoy Rebellion was put down, but not before several massacres of Europeans had occurred and not without a serious military effort by the British, which ended in brutally harsh punishment and executions of some of the mutineers. The mutiny ended the English East India Company. In 1858 the British Crown took over the company’s lands and obligations.

The rest of India came to be known as the “feudal” or “native” states. These were left nominally under the rule of their own princes, who might be fabulously rich sultans, as in Hyderabad, or merely local chieftains. The “native” states were governed through a system of British resident advisers, somewhat like the system later adapted to Nigeria. The India Office in London never hesitated to interfere when it was thought necessary. While it may not have been Britain’s intention, the effect was to allow Britain to “divide and rule” the diverse continent.

Material growth under British rule in India is readily measurable. In 1864 the population of India was about 136 million; in 1904 it was close to 300 million. Although the latter figure includes additional territories in Burma and elsewhere, it is clear that nineteenth- century India experienced a significant increase in total population. In 1901 one male in ten could read and write—a high rate of literacy for the time in Asia; only one in 150 women could read and write.

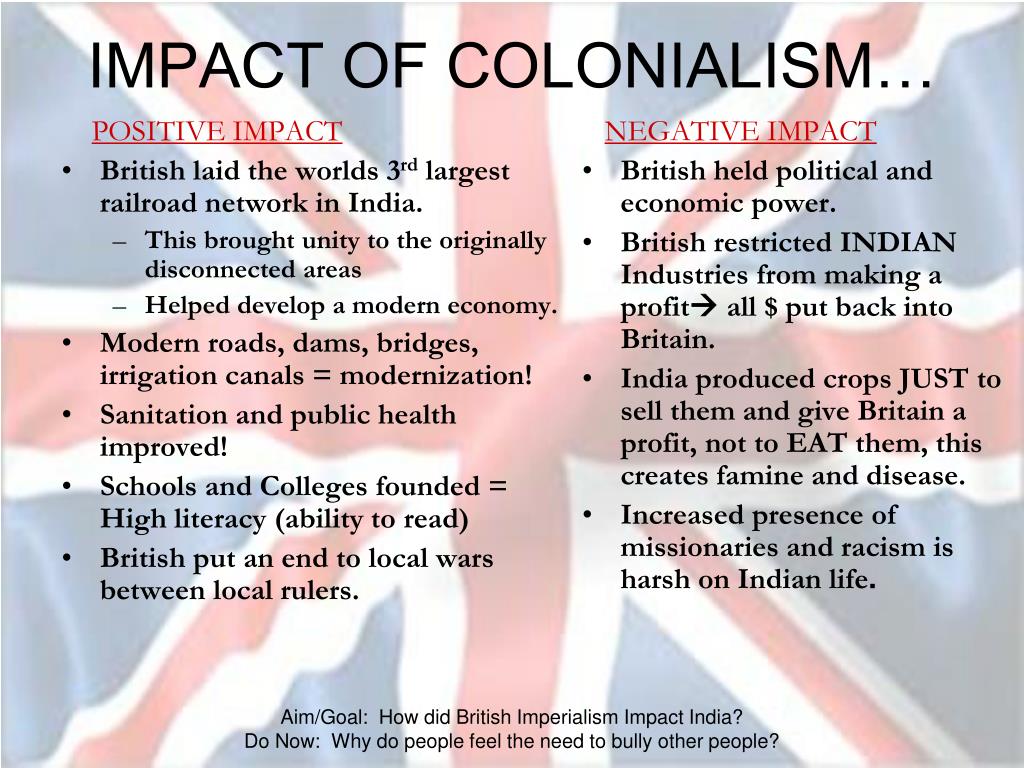

On the eve of World War I India had thousands of miles of railroads, telegraph lines, universities (where classes were conducted in English), hospitals, factories, and busy seaports. Statistics show a native ruling class sometimes fantastically rich, and an immense peasant class for the most part living as their ancestors had lived, at subsistence level. A middle class was just beginning to form, and it had proportionately far more aspirants to white-collar posts in law, medicine, and other liberal professions than to posts in international trade, engineering, and industry—fields badly needed by modernizing societies.

The total wealth of India increased under British rule and was spread more widely among the Indian populations in 1914 than it had been in 1763. Proportionately less and less wealth went directly from an “exploited” India to an “exploiting” Britain. Anglo- Indian economic relations typically took the form of trade between a developed industrial and financial society (Britain) and a society geared to the production of raw materials (India). Indians took an increasing part in this trade, and toward the end of the century local industries, notably textile manufacturing, began to arise in India.

Historians debate whether British rule in India brought social revolution or social stagnation. In some areas society seemed little touched by the transfer of power into British hands, yet in others the rate of colonial impact was startling. Historians do agree, however, that the union between British and Indian ideas and energies was unique:

The humanitarians and evangelicals from Britain were matched by Indian leaders who added their own ethical standards to the desire for change; those British who saw themselves as trustees or guardians were met by Indians who considered themselves a chosen people and who espoused a caste system; and those who stressed duty and the close study of human institutions before attempting to alter them found many Indian thinkers already intent upon dharma (duty) and self- knowledge.

While India had many leaders who drew upon both the British and the Indian ethical arguments, perhaps none blended the several points of view so well as did Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869-1948), who had been admitted to the British bar and had learned of racism firsthand while working for the rights of Indians in South Africa. In 1915 Gandhi returned to India to begin working for the independence of his people.

Throughout the nineteenth century many British “lived off India.” Some of them were in private business, but most were military and civilian workers. Yet Indians were gradually working their way into positions of greater responsibility, into both private and public posts at the policy-making level. Both groups opposed the evolution toward independence for India, because their jobs and sometimes their fortunes depended upon continued colonial status. While the British acknowledged that one day India, and perhaps the great island off its southern tip, Ceylon, would be independent, they did not expect that day to come soon.