The Reformation has often been interpreted, especially by Protestants, as peculiarly modern, forward-looking, and democratic—as distinguished from the stagnant and class-conscious Middle Ages.

This view seems to gain support from the fact that those parts of the West that in the last three centuries have been most prosperous, that have seemed to have worked out democratic government most successfully, and that have often made the most striking contributions to science, technology, and culture were predominantly Protestant.

Moreover, the states that since the decline of Spain after 1600 rose to power and prestige in the West—France, the British Empire, Germany, and the United States—were, with one exception, predominantly Protestant. And the exception, France, had since the eighteenth century a strong element that, though not in the main Protestant, was strongly anticlerical.

The contention that Protestantism is a cause or at least an accompaniment of political and cultural leadership in the modern West needs to be examined carefully.

Protestantism in the sixteenth century was in many ways quite different from Protestantism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. First, sixteenth-century Protestants were not rationalists. They were almost as “superstitious” as the Catholics; it is said that Luther threw his ink bottle at the devil, and Calvinists hanged witches.

The Protestants for the most part shared with their Catholic opponents fundamental Christian concepts of original sin, the direct divine governance of the universe, the reality of heaven and hell. Most important, they did not have, any more than the Catholics did, a general conception of life on this earth as capable of progressing toward a better life for future generations, since the point of life was not to improve the temporal world but to prepare for the spiritual one.

Second, the early Protestants were by no means tolerant and did not believe in the separation of church and state. When they could, they used governmental power to prevent public worship in any form other than their own. Many of them persecuted those who disagreed with them, both Protestants of other sects and Catholics.

Third, the early Protestants were not democratic. Logically, the Protestant change from the authority of the pope, backed by Catholic tradition, to the conscience of the individual believer and a reading of the Bible fits in with developing ideas about individualism, the rights of man, and liberty. But most early Protestant reformers did not hold that all men are created equal. Rather, they believed in an order of rank, a society of status. In this sense, Lutheranism and Anglicanism were clearly conservative in their political and social doctrines. Calvinism can be made to look very undemocratic indeed if a critic concentrates on its conception of an elect few chosen by God for salvation and a majority condemned to eternal damnation. In its early years in Geneva and in New England, Calvinism came close to being a theocracy.

In the long run, however, Calvinism favored domination by a fairly numerous and prosperous middle class, especially in the cities. The most persuasive argument for a causal relationship between Protestantism and modern Western democratic life proceeds less from the ideas of the early Protestants about society than from the way in which Protestant moral ideals strengthened a commercial and industrial middle class.

The Protestant and to a lesser extent the Catholic reformations led to significant changes in the role of women. Catholic males often echoed the church fathers, arguing that Protestantism was a form of hysteria, reflecting the poor intellect and weak will of women, who were said to be instrumental to Protestant thought. Protestants responded by saying that Catholic women were superstitious, immoral, and slothful. These accusations spoke of the rapid changes taking place in the growing cities. In the Renaissance, women took part in the economic life of the city, running shops, supplying venture capital, working as artisans in the textile, clothing, leather, and other trades. Despite this, women were not admitted to political participation, and they generally remained illiterate.

Wealthy women were, by the early sixteenth century, encouraged to read and to use the products of the new printing presses, including the Bible. They often found themselves in disagreement with priests who were unwilling to discuss theological points with them. Protestantism seemed to offer an opportunity, for it encouraged women to read and talk about Scripture in serious ways, often with their husbands, in part so that they might discuss more openly the sacrament of marriage.

Protestant women began to say that they ought to be allowed to preach publicly, while Catholic critics reminded them of Paul’s stern charge, from I Corinthians, that “women keep silence in the churches.” Calvin even permitted wives as well as husbands to initiate divorce proceedings, and Geneva became known as a center of women’s participation in religious matters.

Women remained second-class citizens, but with a difference. In Catholic society, women were honored but were clearly secondary in both church and civil hierarchies. In many Protestant communities, even though women were expected to accept male leadership, if they did so they might enjoy a degree of equality. Indeed, change proceeded rapidly enough to frighten established authorities, and between the late sixteenth and eighteenth centuries women lost a good bit of that which they had gained in the civic sphere.

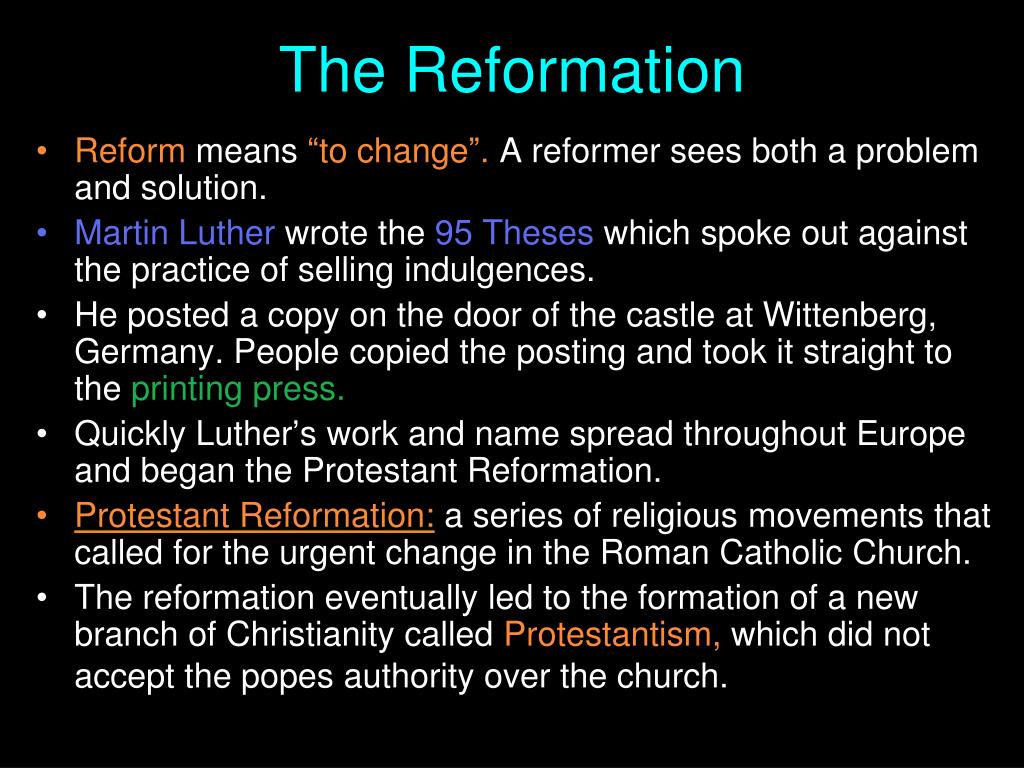

The Protestant Reformation did not create modern society. But it did challenge those in authority in many parts of Europe and did start people thinking about fundamental problems of life in the temporal world as well as in the spiritual one. Its educators and propagandists, using the printing press as a weapon, began a drive for widespread literacy. Thus, the ideas associated with the Reformation helped form the way of life of the middle classes, who were to lay the foundations of modern Western democracy.