In Britain a general election in July 1945—after the war had ended in Europe—ousted Churchill and the Conservative party and for the first time gave the Labour party an absolute majority in the House of Commons.

The Liberal party was practically extinguished. The new prime minister was Clement Attlee (1883-1967), a middle-class lawyer of quiet intellect who was committed to major social reform at home and the decolonization of much of the British Empire abroad.

The new government—with a mandate for social change—proceeded to take over, with compensation to the owners, the coal industry, railroads, and parts of commercial road transportation, and began to nationalize the steel industry. Britain already had a well-developed system of social insurance; this was now capped by a system of socialized medical care for all who wished it. The educational system was partly reformed to make it more democratic and to lengthen the period of compulsory education.

When the Conservatives, with Churchill still at their head, were returned to power in 1951 and remained there for twelve years, they halted the nationalization of steel but otherwise kept intact the socialism of their opponents, including the national health plan. Thus a social revolution was achieved without bitter divisiveness between the parties.

In the postwar years the British were not able to keep up with the extraordinary pace of technological innovation. The British automobile industry, for example, which immediately after the war gained a large share of the world market, yielded the lead in the 1950s to the Germans, with their inexpensive, standardized light car, the Volkswagen.

Furthermore, Britain was one of the last countries in Europe to develop a system of super highways, completing its first modern highway only in 1969. The British were falling behind because they had been the first to industrialize and now their plants were the first to become outdated and inefficient. While British management and labor remained bound to traditional ways, the West Germans, buoyed by vast sums of money provided for their economic recovery by their former enemies, and especially by the United States, embarked on new paths.

Even in apparent prosperity, Britain remained in economic trouble. Continued pressure on the pound in the 1960s repeatedly required help from Britain’s allies to maintain its value. This weakness of the pound signaled an unfavorable balance of trade in which the British were buying more from the rest of the world than they could sell. In the 1950s and 1960s, in what came to be called the “brain drain,” some of Britain’s most distinguished scientists and engineers left home to find higher pay and more modern laboratories in the United States, Canada, or Australia.

Under Harold Wilson (1916– ), a shrewd politician often criticized for opportunism, the Labour party came to power in 1964 and governed until 1970. In 1966 Wilson froze wages and prices in an effort to restore the balance between what the British spent and what they produced. In his own party, such measures were deeply unpopular and were regarded as exploiting the poor to support the rich.

Wilson had to devalue the pound after heavy foreign pressure against it. Despite the unpopularity of his policies, by 1969 the deficits had disappeared and general prosperity continued, along with high taxes and rapid inflation. Prices were rising so fast that the gains from rising wages were largely illusory. The national health plan and education for working-class mothers had freed more women for an increasingly technical work force.

But a spiral continued with only momentary breaks, regardless of the party in office, and except for a period of prosperity and relative confidence in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Britain’s decline in relation to its competitors continued. By the 1980s, when the Conservative Margaret Thatcher (1925— ) was prime minister, British inflation had been lessened but still remained dangerously high, unemployment stood at depression levels, and the British standard of living had been surpassed by most nations in western Europe.

Even so, conditions of life improved for most people. The Labour government had imposed heavy income taxes on the well-to-do and burdensome death duties on the rich, using the income thus obtained to redistribute goods and services to the poor. An increasing number of new universities offered young people of all classes educational opportunities that had previously been available only to the upper and upper-middle classes.

In the postwar years race became serious issue in Britain for the first time. Indians, Pakistanis, West Indians, and Africans—Commonwealth subjects with British passports—left poor conditions at home and migrated freely to Britain in large numbers to take jobs in factories, public transportation, and hospitals. Despite its liberal and antiracist protestations, the Wilson government was forced to curtail immigration sharply. Some Conservative politicians predicted bloody race riots (which, in fact, occurred in 1981) unless black immigration was halted, and some extremists proposed that nonwhites already in Britain be deported.

Closely related to the race issue at home was the question of official British relations with southern Africa, to which the Labour government refused to sell arms because of the apartheid policies of the South African regime from the late 1940s. Brought gradually into place from 1948 to the late 1960s, apartheid laws (the term means “apartness”) led to separate tracks of development for whites, blacks, coloureds, and Asians: a complex and highly expensive system of segregation by race.

Relations deteriorated quickly after South African police fired upon a mass demonstration at Sharpeville in 1960, killing many black Africans. In 1961, under pressure from the prime ministers of Canada and India and with Britain’s approval, the rigidly racist government of South Africa withdrew from the Commonwealth.

To this strain was added a major challenge to British authority when the white-dominated government in Southern Rhodesia, unwilling to accept a constitution that provided for full black participation in legislation, unilaterally declared Rhodesia independent of Great Britain, citing the American colonies in 1776 as a precedent. This move led to the imposition of sanctions by the United Nations and years of delicate negotiations punctuated by civil war, until a cease-fire, a constitution, and elections were ultimately accepted by all parties, and the Thatcher government declared Rhodesia independent, as Zimbabwe, in 1980.

Perhaps most persistently debilitating to British security, however, was the Irish problem, long quiescent, which arose again in the late 1960s. In Ulster (the northern counties that were still part of the United Kingdom), the Catholics generally formed a depressed class and were the first to lose their jobs in bad times.

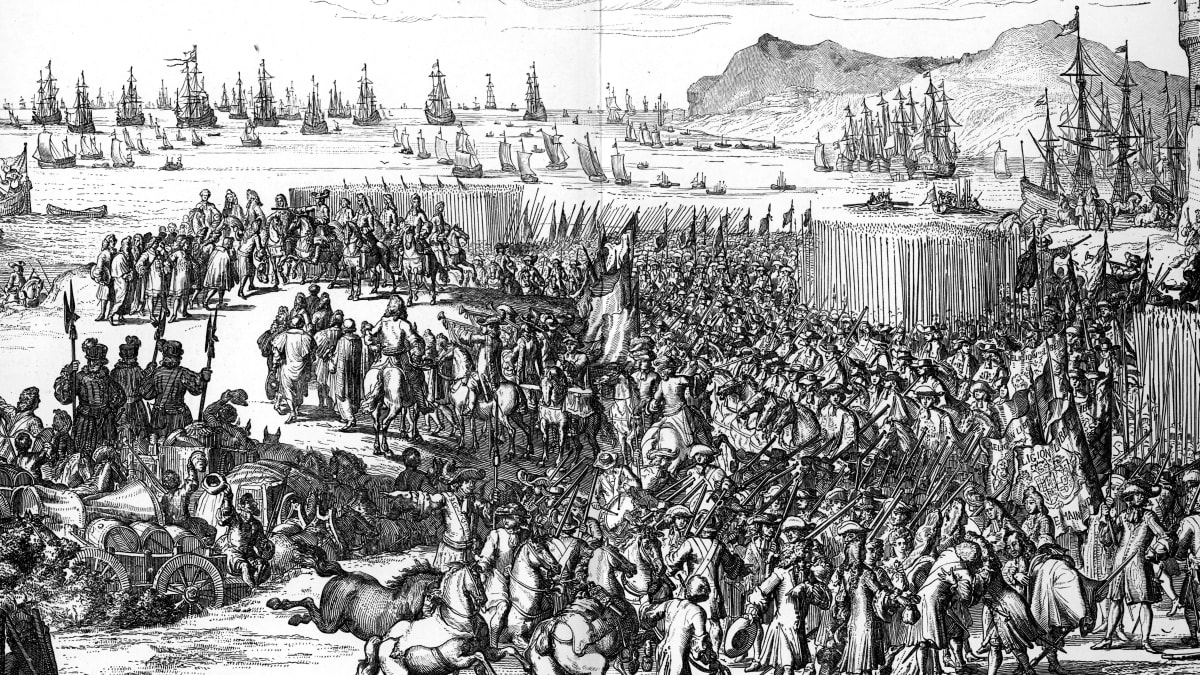

They were inflamed by the insistence of Protestant extremists (the Orangemen) on publicly celebrating the anniversaries of victories of William III in the 1690s that had ensured English domination over the region. Marching provocatively through Catholic districts, the Orangemen in the summer of 1969 precipitated disorders that began in Londonderry and spread to Belfast and other areas. The regular police were accused by Catholics of being mere tools of the Protestant oppressor and had to be disarmed. The British army then intervened to keep order.

The government of Eire suggested that the United Nations be given responsibility for the problem, a suggestion unacceptable to both the Northern Irish and British governments. Extremists of the south, the Irish Republican Army (IRA), who had always claimed the northern counties as part of a united Ireland, now revived their terroristic activities. But the IRA itself was split between a relatively moderate wing and the Provisionals (Provos), anarchists dedicated to nearly indiscriminate bombing.

The level of fighting steadily escalated in Northern Ireland. In 1972 the British suspended the Northern Irish parliament and governed the province directly. In 1981 a group of prisoners, insisting that they not be treated as common criminals but as political prisoners, resorted to hunger strikes; although ten prisoners died, the British government continued to refuse political status to people they viewed as terrorists. In early 1995 there at last appeared the prospect of an enduring cease-fire.

Yet Britain was by no means wholly gloomy or depressed. Many British products continued to set the world’s standards, especially for the upper classes. Beginning with the enormous popularity and stylistic innovations of the Beatles in the early 1960s, England for a time set the style for young people in other countries. Long hair for men, the unisex phenomenon in dress, the popularity of theatrical and eccentric clothes, the whole “mod” fashion syndrome that spread across the Atlantic and across the Channel started in England.

Carnaby Street, Mick Jagger (1943– ), and the Rolling Stones all had their imitators elsewhere, but the originals were English. Thus Britain continued to play a major role in fashion, music, social attitudes, and in tourism, through a tourist boom that brought millions of visitors to Britain, making it the front-ranking tourist nation in the world.

Most evident was the gradual erosion of rigid class distinctions in England, traditional bastion of political freedom and social inequality. The Beatles were all working-class in origin; lower class, too, were most leading English pacesetters of the new styles in song, dress, and behavior. These styles spread not only abroad, but among the middle and upper classes of the young in Britain as well, who were increasingly impatient to have done with the class sentiment that had so long pervaded English thought. By the 1990s even the monarchy, once revered, came under increasing criticism.

This impatience reflected the growing fragmentation of British social and economic life. The Labour party suffered from chronic disunity. In 1980 some of its members founded the Social Democratic party, hoping to take up the middle ground politically through an alliance with the remnant of the Liberals, but by the end of the decade this effort was dead.

In 1982 a successful war with Argentina, occasioned by that country’s attempt to occupy the Falkland Islands, buoyed national spirits, but Prime Minister Thatcher’s popularity fell as unemployment continued to rise, even though she won her third election victory in 1987.

On October 19, Black Friday, the stock market came down with a bump, and thereafter her popularity waned. An unpopular poll tax imposed in 1990 led to street riots. In November she resigned, having been in office for eleven and a half years.