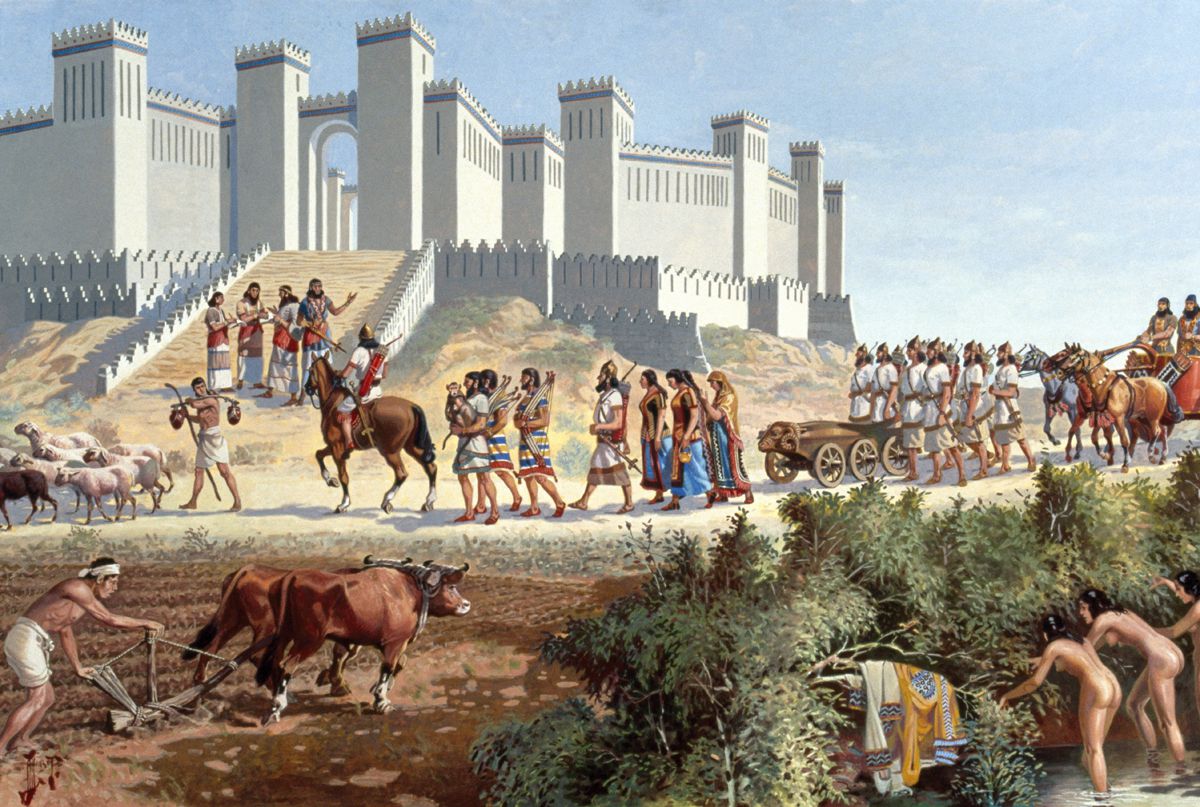

What the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers did for Mesopotamia, the Nile River did for Egypt. Over thousands of years the people along the Nile had slowly learned to take advantage of the annual summer flood by tilling their fields to receive the silt-laden river waters, and by regulating its flow. About 3000 B.C., at approximately the time that the Sumerian civilization emerged in Mesopotamia, the Egyptians had reached a comparable stage of development.

Egypt, though also a hydraulic society based on river-valley agriculture, was more dynamic, perhaps more willing to entertain new ideas than the Mesopotamian states had been. The Egyptians regarded life after death as a happy continuation of life on earth, not as a dismal eternal sojourn in the dust. The Mesopotamian rulers— both the early city lords and the later kings who aspired to universal monarchy—were agents of the gods on earth; the Egyptian rulers from the beginning were themselves regarded as gods.

Because Egyptian territory consisted of the long strip along the banks of the Nile, it was always hard to unify. It was, however, rich in agricultural resources and relatively easy to defend, and in time it became the world’s first centralized state. At the very beginning (3000 B.C.) there were two rival kingdoms: Lower and Upper Egypt. Lower Egypt was the Nile Delta, the triangle of land nearest the Mediterranean where the river splits into several streams and flows into the sea.

Upper Egypt was the land along the course of the river for eight hundred miles between the Delta and the First Cataract. Periodically the two regions were unified into one kingdom, but the ruler, who called himself king of Upper and Lower Egypt, by his very title recognized that his realms consisted of two disparate entities. The first unifier, perhaps mythical, was Menes, whose reign (about 2850 B.C.) is taken by scholars as the start of the first standard division of Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom (2700-2160).