In the late nineteenth century French prospects in Egypt seemed particularly bright.

Between 1859 and 1869 the private French company headed by Ferdinand de Lesseps built the Suez Canal, which united the Mediterranean with the Red Sea and shortened the sea trip from Europe to India and the Far East by thousands of miles. The British had opposed the building of this canal under French patronage; but now that it was finished, the canal came to be considered an essential part of the lifeline of the British Empire.

The British secured a partial hold over this lifeline in 1875, when Disraeli arranged the purchase of 176,000 shares of stock in the canal company from the financially pressed khedive (prince) Ismail (r. 1863-1879). The shares gave Britain a 44 percent interest in the company. Despite the sale of the stock, Ismail’s fiscal difficulties increased. The Egyptian national debt, which was perhaps £3.3 million at his accession, rose to £91 million by 1876. That year, the European powers (from whose private banks Ismail had borrowed large sums at high interest) obliged Egypt to accept the financial guidance of a debt commission that they set up.

Two years later Ismail had to sacrifice still more sovereignty when he was obliged to appoint an Englishman as his minister of finance and a Frenchman as his minister of public works to ensure that his foreign creditors had first claim to his government’s revenues.

In 1879, Ismail himself was deposed. Egyptian nationalists, led by army officers whose pay was drastically cut by the new khedive as an economy move, revolted against foreign control and against the government that had made this control possible. Using the slogan “Egypt for the Egyptians!” the officers established a military regime that the powers feared would repudiate Egyptian debts or seize the Suez Canal. In 1882 the British and French sent a naval squadron to Alexandria, ostensibly to protect their nationals.

A riot there killed fifty Europeans. The Egyptian military commander began to strengthen the fortifications at Alexandria, but the British naval squadron destroyed the forts and landed British troops, declaring that they were present in the name of the khedive to put an end to the disorders. The khedive gave the British authority to occupy Port Said and points along the Suez Canal to ensure freedom of transit. Thus Britain acquired the upper hand in Egypt, taking the canal and occupying Cairo. Dual French-British control was over.

By the eve of World War I Britain exercised virtual sovereignty over Egypt. Legally, Egypt was still part of the Ottoman Empire, and the khedive’s government remained; but a British resident adviser was always at hand to exercise control, and each ministry was guided by a British adviser. For a quarter of a century this British protectorate was in the hands of an imperial proconsul, Evelyn Baring, Lord Cromer (1841-1917), Resident in Cairo from 1883 to 1907.

Under Cromer and his successors the enormous government debt was systematically paid off and a beginning made at Westernizing the economic base of Egypt. But nationalist critics complained that too little was being spent on education and public health, and that British policy was designed to keep Egypt in a perpetual colonial economic status, exporting long-staple cotton and procuring manufactured goods from Britain rather than establishing home industries.

Egyptian nationalists were also offended by British policy toward the Sudan. This vast region to the south of Egypt had been partially conquered by Muhammad Ali and Ismail, then lost in the 1880s as a result of a revolt by an Islamic leader, Muhammad Ahmad (c. 1844-1885), who called himself the mandi (messiah). Fears that France or some other power might gain control over the Nile headwarters prompted Britain to reconquer the Sudan. The reconquest at first went very badly for the British.

An Egyptian army under British leadership was annihilated. The British press trumpeted for revenge, and General Charles George Gordon (1833-1885) was dispatched to Khartoum, the Sudanese capital. But Gordon was surrounded in Khartoum. A relief expedition to rescue Gordon left too late, and after passing most of 1884 under siege, Khartoum fell to the Mandists on January 26, 1885, sixty hours before relieving steamers arrived. Gordon died in this final battle of the siege. Finding Khartoum occupied by the Mandists, the expedition retired.

National pride required the avenging of Gordon and the reconquest of the Sudan. This was achieved by Lord Kitchener (1850-1916) in an overwhelming victory against the Mandists at Omdurman in 1898. Between the defeat of Gordon and the battle of Omdurman the British had exploited their technological superiority. They had extended the rail line from Cairo into the heart of the Mandists’ land, and they had equipped their troops with new rifles, the Maxim machine gun, and field artillery. The Mandists were armed with spears and muzzle-loading muskets. At Omdurman the Mandists were destroyed and the superiority of European arms definitively established.

A week later news reached Kitchener that French troops were at Fashoda, within the Sudan and on the upper Nile, having crossed from the Atlantic coast. Fearing that the French intended to dam the Nile and block new irrigation for Egypt, Kitchener pressed on toward Fashoda. The French withdrew and renounced all claim to the Nile valley. The British made the Sudan an Anglo- Egyptian condominium (joint rule), of which they were the senior partner. This assured clear British dominance in Egypt, since they now controlled the source of the water supply, and it assuaged public opinion in Britain, which had clamored for war; but it aroused Egyptian nationalists, who feared Egypt had lost a province rightfully belonging to it alone.

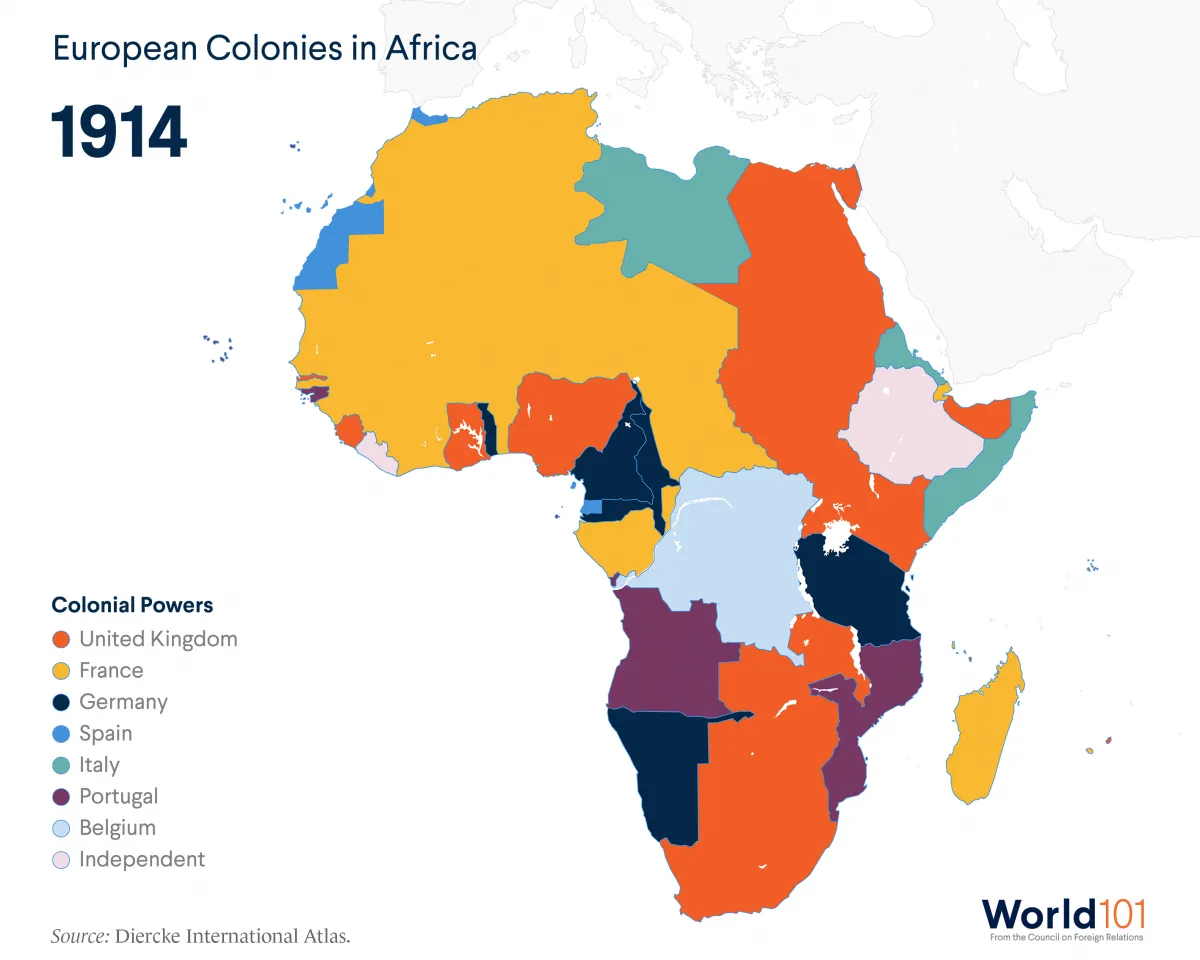

The British steadily added to their African possessions throughout the century. At its end they had the lion’s share of the continent. They had only 4 million square miles out of more than 11 million, but they controlled 61 million people out of some 100 million. The most significant areas were in West Africa. Sierra Leone had been founded after a British judge, Lord Mansfield (1772), had decided that slaves could not be held in England.

Seeking some place for free blacks, the British established the “province of freedom” in 1787, adding to its population by bringing in slaves who had fled to freedom behind British lines during the American Revolution. More important in terms of resources and strategic location was the Gold Coast, acquired by the defeat of the Ashanti in 1874 and, more completely, in 1896 and 1900. The whole of Ashantiland was formally annexed in 1901.

The most important, however, was the colony and protectorate of Nigeria, to which one of Britain’s ablest administrators, Sir Frederick (later Lord) Lugard (18581945), applied a method of colonial governance known as indirect rule. Centering on the great River Niger, Nigeria was formally put together from earlier West African colonies in 1914. Northern Nigeria was ruled by Muslim emirs of the Fulani people; southern Nigeria was inhabited by divided groups that had long been harassed by slave raids. The region over which the British asserted control comprised the lands of the Hausa, Yoruba, and Ibo peoples—the first Muslim, the others increasingly converted by Christian missionaries, and all three in conflict with each other.

In the Americas, Britain maintained its colonial dependencies in the Caribbean, in Bermuda and the Bahamas, and on the mainland in British Honduras (now Belize) and British Guiana (now Guyana). Tiny dependencies were held as well in the Atlantic, in particular the Falkland Islands, to which the independent nation of Argentina periodically asserted a claim.

These were all tropical or semitropical lands, with a relatively small planter class, large black or “brown” lower classes, and often a substantial commercial class from South Asia. The West Indies suffered gradual impoverishment as a result of the competition offered to the local cane sugar crop by the growth in other countries of the beet sugar industry, together with an increase in population beyond the limited food resources of the region. By 1914 the once proud “cockpit of the British Empire” had become an impoverished “problem area.”

As racism grew in most of the West toward the end of the century, the African and West Indian colonies tended to be lumped together in the official mind of British imperialists. Racial disharmony became more common, but it did not reach its peak in the British Empire until the 1920s and early 1930s, when white settlers moved in substantial numbers into Kenya and the Rhodesian highlands. Nor would racist arguments be applied so stringently to the Asian areas of the empire, even though a sense of European superiority became ever more apparent.