Khrushchev now probed in another way, announcing in August 1961 that the Soviets would resume atomic testing in the atmosphere, a practice stopped by both powers in 1958.

In the two months that followed, the Soviets exploded thirty bombs. President Kennedy decided that, unless Khrushchev would agree to a treaty banning all tests, the United States would have to conduct its own new tests. Khrushchev refused, and American testing began again in April 1962.

In the summer of 1962 Khrushchev moved to place Soviet missiles with nuclear warheads in Cuba. This former American dependency and economic satellite, which was of great strategic importance and which lay only ninety miles off the Florida coast, was now in the hands of a domestic Communist party led by Fidel Castro (1926– ).

Castro had overthrown Cuba’s dictator, General Fulgencio Batista (1901-1973), in 1959. Castro’s revolution, which had taken nearly six years, had at first seemed romantic and had been supported by many Americans. Once in power, Castro quickly entered into an alliance with the Soviets. Hoping to bring Castro down, anticommunist Cuban exiles in the United States had attempted a disastrous landing at the Bay of Pigs in 1961.

Castro quickly learned what it meant to be a Soviet satellite during the Cuban missile crisis. He may not have asked for the missiles, but he had accepted them, even though Soviet officers were to retain control over their use. Although their installation would effectively have doubled the Soviet capacity to strike directly at the United States, the chief threat was political.

When known, the mere presence of these weapons ninety miles from Florida would shake the confidence of other nations in America’s capacity to protect even its own shores, and would enable Khrushchev to blackmail America over Berlin. American military intelligence discovered the sites and photographed them from the air. Khrushchev announced that the Soviet purpose was simply to help the Cubans resist a new invasion from the United States.

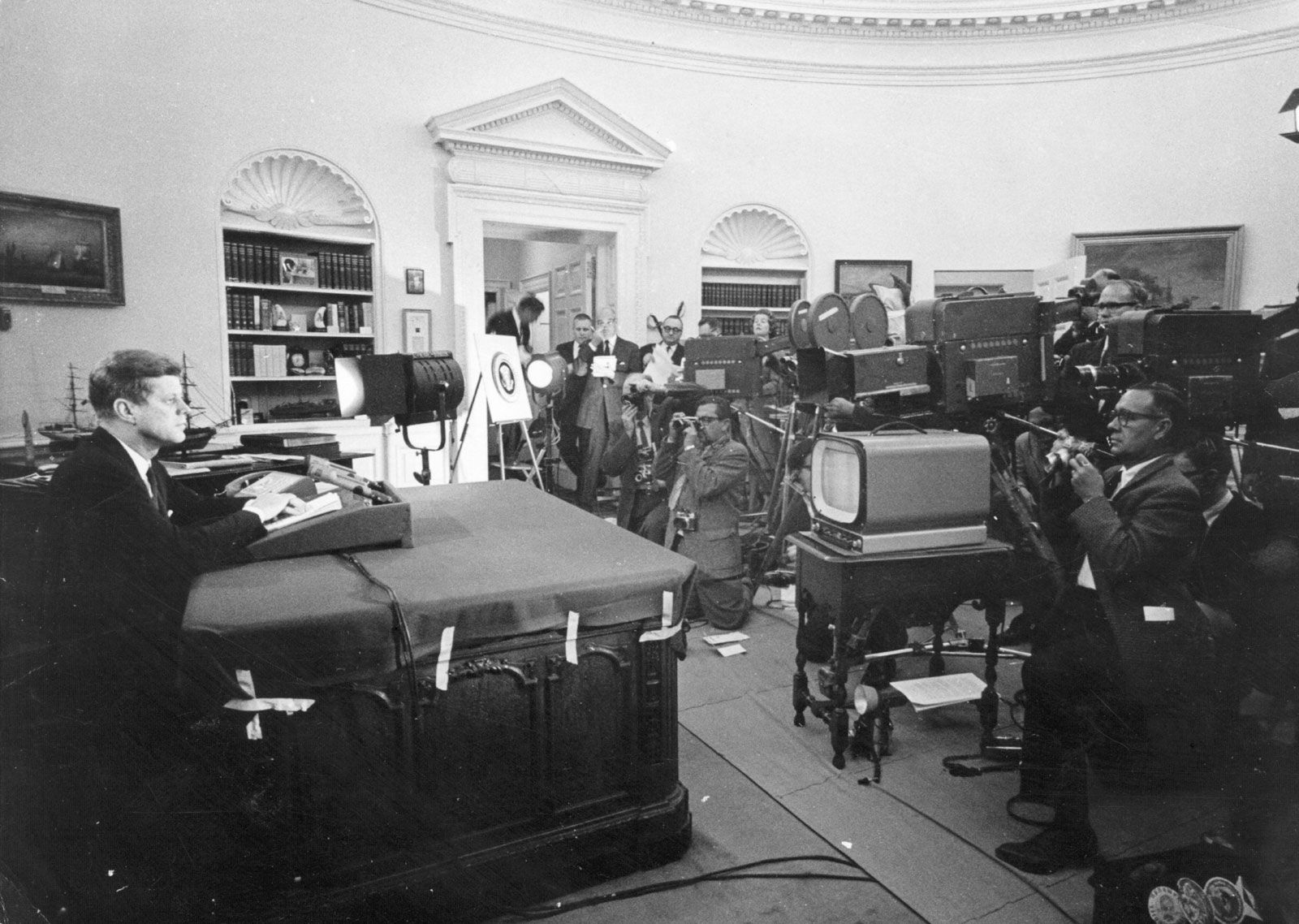

But Kennedy could not allow the missiles to remain in Cuba. At first the only course of action seemed an air strike, which might well have touched off a new world war. Instead, Kennedy found a measure that would prevent the further delivery of missiles—a sea blockade (“quarantine”) of the island—and he combined it with the demand that the missiles already in Cuba be removed. After several days of great tension, Khrushchev backed down and agreed to halt work on the missile sites in Cuba and to remove the offensive weapons there.

Kennedy now exploited the American victory to push for a further relaxation in tensions. In July 1963 the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain signed a treaty banning nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere, in outer space, or underwater. The treaty subsequently received the support of more than seventy nations, though France and the PRC—prospective nuclear powers—would not sign it.

The installation of a “hot line” communications system between the White House and the Kremlin that enabled the leaders of the two superpowers to talk to each other directly, and the sale of surplus American wheat to the Soviets marked the final steps Kennedy was able to take to decrease tensions before he was assassinated on November 22, 1963.