The constitution of the Year VIII was the fourth attempt by revolutionary France to provide a written instrument of government, its predecessors being the constitutions of 1791, 1793, and 1795. The new document erected a very strong executive, the Consulate.

Although three consuls shared the executive, Napoleon as first consul left the other two only nominal power. Four separate bodies had a hand in legislation: The Council of State proposed laws; the Tribunate debated them but did not vote; the Legislative Corps voted them but did not debate; the Senate had the right to veto legislation.

The members of all four bodies were either appointed by the first consul or elected indirectly by a process so complex that Bonaparte had ample opportunity to manipulate candidates. The core of this system was the Council of State, staffed by Bonaparte’s hand-picked choices, which served both as a cabinet and as the highest administrative court.

The three remaining bodies were intended merely to go through the motions of enacting whatever the first consul decreed. Even so, they were sometimes unruly, and the Tribunate so annoyed Napoleon that he finally abolished it in 1807.

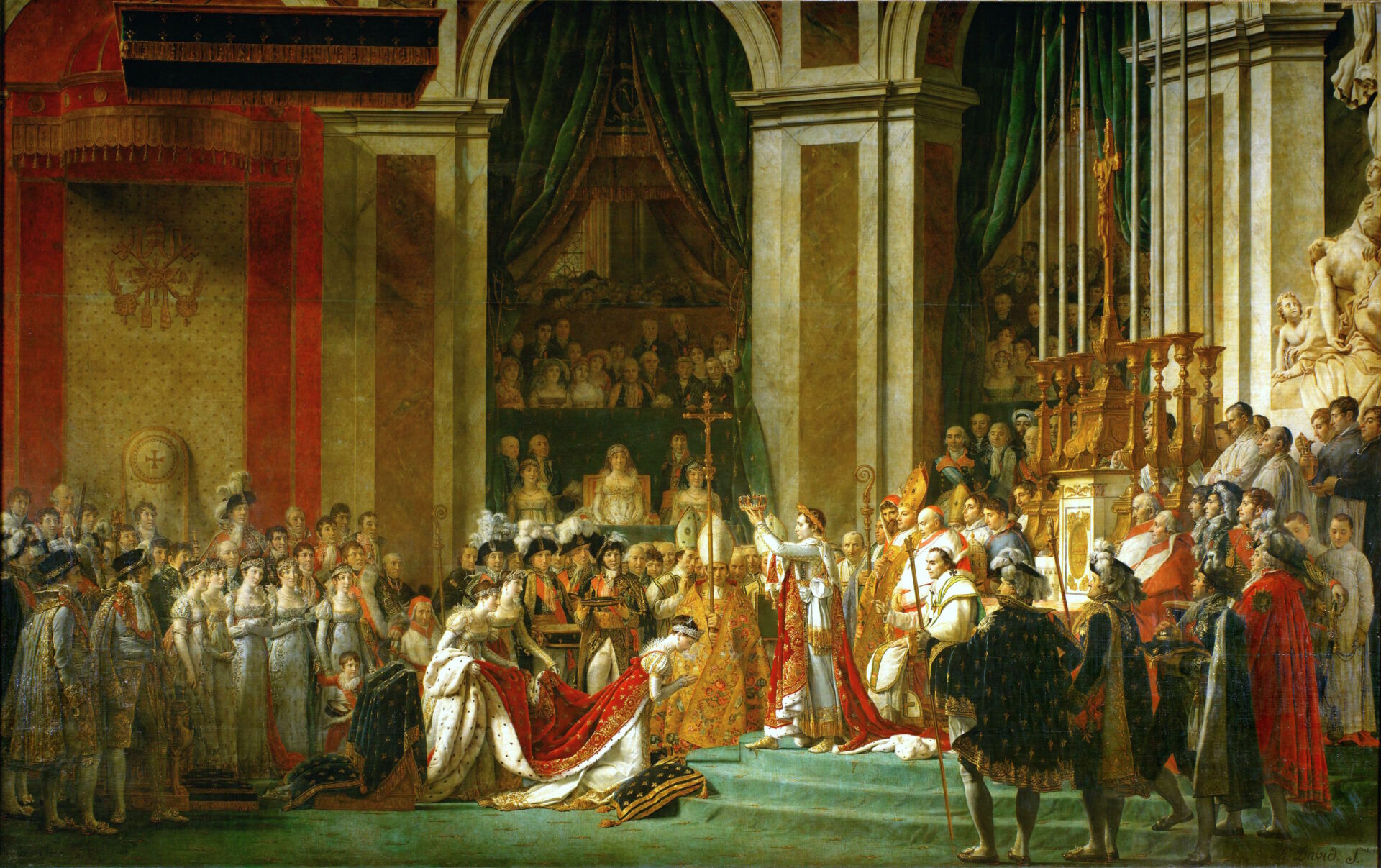

Meantime, step by step, Napoleon increased his own authority. In 1802 he persuaded the legislators to make him first consul for life, with the power to designate his successor and to amend the constitution at will. France was now a monarchy again in all but name. In 1804 Napoleon prompted the Senate to declare that “the government of the republic is entrusted to an emperor.” A magnificent coronation took place at Notre Dame in Paris on December 2. The pope consecrated the emperor, but, following Charlemagne’s example, Napoleon placed the crown on his own head.

Each time Napoleon revised the constitution in a nonrepublican direction, he made the republican gesture of submitting the change to the electorate. Each time the results were overwhelmingly favorable: In 1799-1800 the vote was 3,011,107 for Napoleon and the constitution of the Year VIII, and 1,562 against; in 1803 it was 3,568,885 for Napoleon and the life consulate, and 8,374 against; in 1804 it was 3,572,329 for Napoleon and the empire, and 2,579 against.

Although the voters were exposed to considerable official pressure and the announced results were perhaps rigged a little, the majority in France undoubtedly supported Napoleon. His military triumphs appealed to their growing nationalism, and his policy of stability at home ensured them against further revolutionary crises and changes.

Men of every political background now staffed the highly centralized imperial administration. Napoleon cared little whether his subordinates were returned emigres or ex-Jacobins, so long as they had ability. Besides, their varied antecedents reinforced the impression that narrow factionalism was dead and that the empire rested on a broad political base.

Napoleon paid officials well and offered the additional inducement of high titles. With the establishment of the empire he created dukes by the dozen and counts and barons by the hundred. He rewarded outstanding generals with the rank of marshal and other officers with admission to the Legion of Honor, which also paid its members an annual pension. “Aristocracy always exists,” Napoleon remarked. “Destroy it in the nobility, it removes itself to the rich and powerful houses of the middle class.”