In the Britain of the 1820s, the new industrialists had small opportunity to mold national policy. Booming industrial cities like Manchester and Birmingham sent not a single representative to the House of Commons.

A high proportion of business leaders belonged not to the Church of England but were nonconformists who still suffered discrimination when it came to holding public office or sending their sons (not to speak of their daughters) to Oxford or Cambridge. Even in France, despite the gains made since 1789, the bourgeoisie often enjoyed only second-class status.

In western Europe the middle classes very soon won the place they felt they deserved; in Britain a gradual process of reform gave them substantially all they wanted. The high spot was the Reform Bill of 1832, which extended the suffrage to the middle class. In 1830 the French bourgeoisie got their citizen-king. In Piedmont the middle class secured at least a narrowly liberal constitution in 1848. In southern and central Europe, by contrast, the waves of revolution that crested in 1848 left the bourgeoisie frustrated and angry.

The grievances of workers were more numerous than those of their masters, and they seemed harder to satisfy. The difficulties may be illustrated by the protracted struggle of laborers to secure the vote and to obtain the right to organize and to carry on union activities. In Britain substantial numbers of workers first won the vote in 1867, a generation after the middle class did. In France universal male suffrage began in 1848. The unified German Empire had a democratic suffrage from its inception in 1871, but without some other institutions of democracy. Elsewhere, universal manhood suffrage came slowly—not until 1893 in Belgium, and not until the twentieth century in Italy, Austria, Russia, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and (because of restrictions on black voters) the United States.

During most of the nineteenth century, labor unions and strikes were regarded by employers as improper restraints on the free operation of natural economic laws; accordingly, a specific ban on such combinations, as they were termed, had been imposed by the British Combination Acts at the close of the eighteenth century. Parliament moderated the effect of these acts in the 1820s but did not repeal them until 1876. Continental governments imposed similar restrictions. France’s Loi de Chapelier was relaxed only in the 1860s and repealed in 1884. Everywhere labor slowly achieved full legal recognition of the legitimacy of union activities: in 1867 in Austria, in 1872 in the Netherlands, and in 1890 in Germany.

Labor’s drive for political and legal rights, however, was only a side issue during the early industrial revolution. Many workers faced the more pressing problems of finding jobs and making ends meet on wages that ran behind prices. The Western world had long experienced the business cycle, with its alternation of full employment and drastic layoffs; the industrial revolution intensified the cycle, making boom periods more hectic and depressions more severe. At first factories made little attempt to provide a fairly steady level of employment. When a batch of orders came in, machines and workers were pushed to capacity until the orders were filled; then the factory simply shut down to await the next orders.

Excessively long hours, low pay, rigorous discipline, and dehumanizing working conditions were the most common grievances of early industrial workers. Many plants neglected hazardous conditions, and few had safety devices to guard dangerous machinery. Cotton mills maintained the heat and the humidity at an uncomfortable level because threads broke less often in a hot, damp atmosphere. Many workers could not afford decent housing, and if they could afford it, they could not find it. Some few of the new factory towns were well planned, with wide streets and space for lawns and parks. Some had an adequate supply of good water and arrangements for disposing of sewage, but many had none of these necessities.

The industrial nations also threatened to remain nations of semiliterates; until they made provision for free public schools during the last third of the nineteenth century, education facilities were grossly inadequate. In England, as often as not, only the Sunday school gave the mill hand’s child a chance to learn the ABCs. A worker with great ambition and fortitude might attend an adult school known as a “mechanics’ institute.” In the 1840s a third of the men and half of the women married in England could not sign their names on the marriage register and simply made their mark.

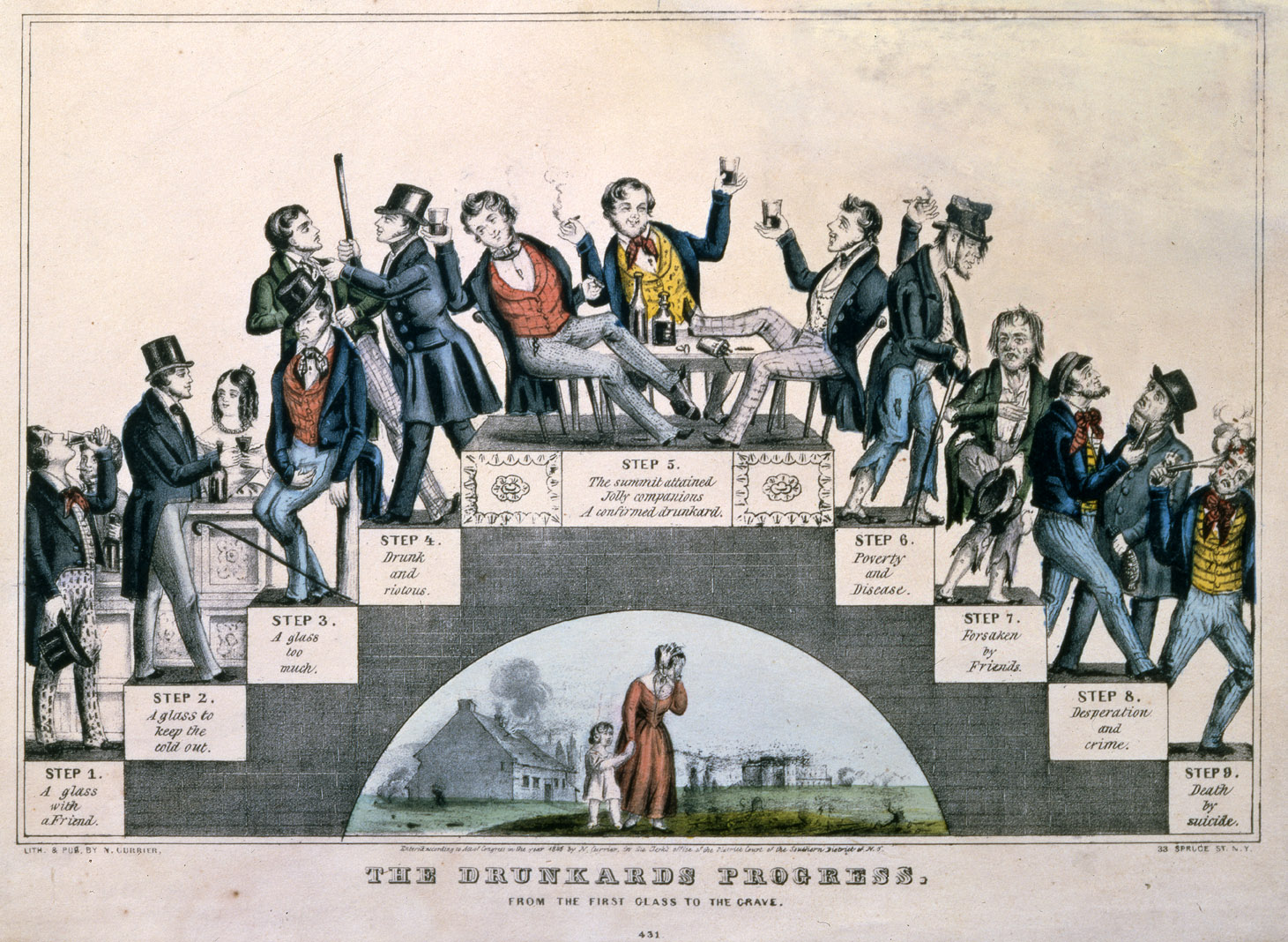

Laborers did attempt to join the ranks of the middle class by adhering to the precepts of thrift, hard work, and self-help. Samuel Smiles (1812-1904) pointed the way in a number of books with didactic titles such as Character, Thrift, and Duty, which preached a doctrine of self- salvation. Through joining a temperance society and by regular attendance at a worker’s institute, a laborer might rise to become a master cotton spinner, a head mechanic, even a clergyman, shopkeeper, or schoolmaster. For some, the demands of hard work, self-reliance, and adherence to duty paid off in upward social mobility; for others, life was a round of exploitation, poverty, and demoralization. For many, alcohol was a way of forgetting the demands of the day, prostitution a means of income, religion a path to peace of mind.

Preceding the revolutions of 1848, Europeans discussed at length the “social question,” or, as it was called in Britain, “the condition-of-England question”; these terms were code language for pauperism and the evident decline of the lower classes. Pauperism was most visible in the cities, though conditions of poverty may in fact have been harsher in the countryside. Many social observers, while welcoming the clear benefits arising from industrialization, predicted that social calamity lay ahead.

Some thought overpopulation was the main problem and suggested that “redundant populations” be sent overseas to colonies; others thought the problem lay in the decline of agriculture, forcing mechanically unskilled workers to migrate to the cities; yet others thought the oppressive conditions were limited to specific trades and locations. None could agree whether the overall standard of living was increasing for the majority, if at the cost of the minority—nor can historians agree today.

Historians generally do agree on some conclusions, however. There was an aggregate rise in real wages, which went largely, however, to the skilled worker, so that the working class was really two or more classes. Prices for the most basic foodstuffs declined, so that starvation was less likely. Conditions of housing worsened, however, and the urgency of work increased. Workers in traditional handicrafts requiring specialized skills might now have meat on their table three times a week, but workers displaced by a new machine might not have meat at all. Fear of unemployment was commonplace.

A mill hand could barely earn enough to feed a family of three children if fully employed; economic necessity compelled him to limit the size of his family, and he had to remain docile at work to assure that he would remain employed. Dependence on public charity, with its eroding effects on self- confidence, was necessary during periods of layoffs in the factory. Women and children were drawn increasingly into the labor force, since they would work at half a man’s wage or less, and this led to tension between the sexes, since men saw their jobs being taken by women. In Britain, France, Belgium, and Germany half the mill employees were boys and girls under eighteen.

Work began at dawn and ended at dusk; there was no time for leisure, and often the only solace was in sex, increasing the size of the family and adding to the economic burdens of the parents. Food was dreary and often unhealthy: bread, potatoes, some dubious milk, turnips, cabbage, on occasion bacon. Meat was a luxury; in the sixteenth century the average German was estimated to consume two hundred pounds of meat in a year: in the nineteenth century, forty pounds.

The workingman and workingwoman, as well as the working child, lived at the margin of existence. Yet they did live, as their predecessors might not have done. There was a “hierarchy of wretchedness” that was relative rather than absolute, but now was felt all the more acutely.