Most of the precedents by which the British Empire evolved into a commonwealth of self-governing nations were first developed in Canada. Between 1783 and 1931 Canada became the first dominion, fully independent from at least 1931 and probably earlier, and essentially self-governing from 1867.

The defeat of the British in the American Revolution propelled thousands of loyal Tories northward to start life anew in Canada as United Empire Loyalists. These Loyalists wished protection from the French; they wished to secure their rights as Englishmen; and they wished to set themselves clearly apart from the new republic to the south. The result was a history of constitutional changes that provided the pattern for other colonies.

Some of these changes arose from Loyalist demands, some from the need to achieve a balance between French-language and English-language interests, and some from the need for protection against an expanding United States.

First was the Constitutional Act of 1791, establishing elective assemblies in both Upper and Lower Canada, the first almost exclusively British and the second largely French. A constitutional struggle between the elective assemblies and the governors followed, with the central issues being the collecting of revenue, the granting of land for settlement, and the powers of the judiciary. Deadlock resulted by 1837.

Rebellion followed. In Upper Canada William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861), “the Firebrand,” led a popular uprising. In Lower Canada Louis-Joseph Papineau (1786-1871) rallied the disgruntled in Montreal. When the mass of the population remained aloof, the two rebel leaders were easily defeated and fled to the United States. Relations with the U.S.—which had remained strained since the War of 1812, during which American militia had burned York (present-day Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada—deteriorated further. Recognizing the dangers of continued discontent within its North American provinces, Britain sought pacification.

The solution was proposed in the Durham Report. Lord Durham (1792-1840), a Whig, was sent to Canada by the British to be governor-general with sweeping investigative powers. Concluding that two cultures were “warring within the bosom of a single state,” Durham’s massive 1839 Report on the Affairs of British North America proposed a union of the two Canadas, the British and the French, and the grant of full responsible government to the united colony.

Britain would retain control over foreign relations, the regulation of trade, the disposal of public lands, and the nature of the constitution, surrendering all other aspects of administration to local authorities. The sense of the Durham Report was embodied in the Union Act of 1840 and in the governorship of Lord Elgin (1847-1854), who in 1849 refused to veto the Rebellion Losses Bill, intended to compensate those who had suffered losses in the uprisings of 1837.

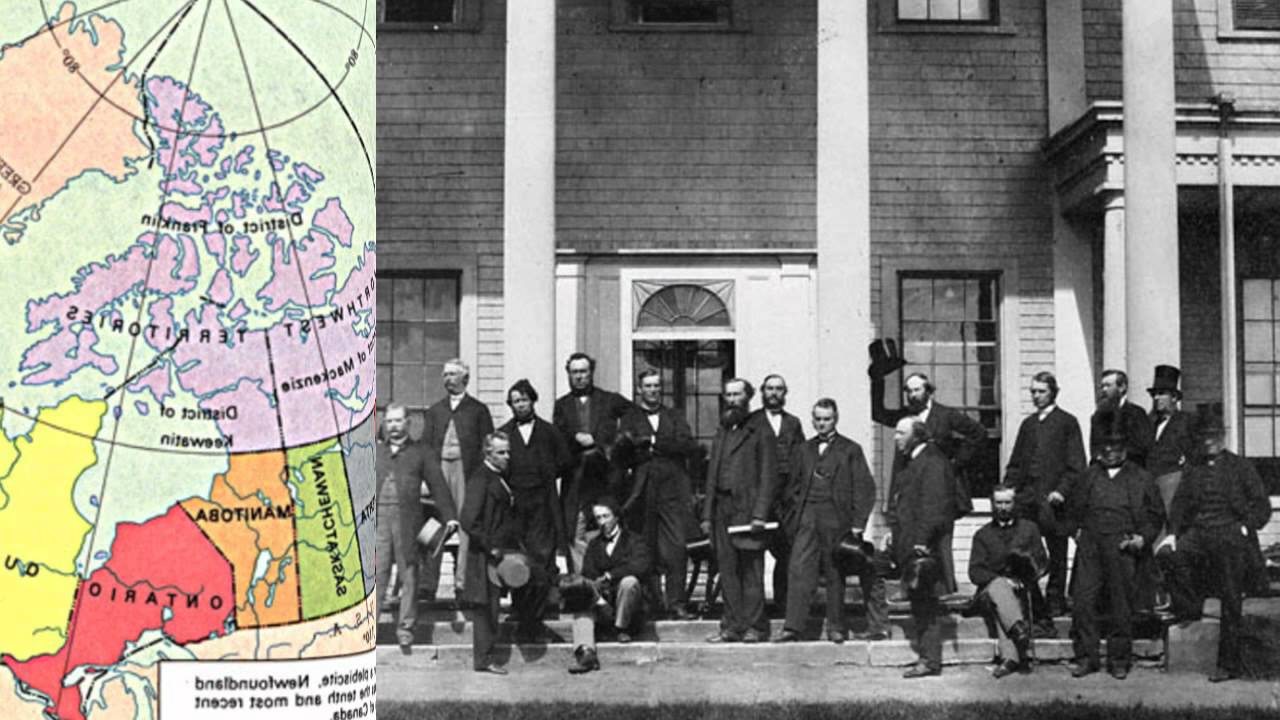

The American Civil War sped the next phase of constitutional growth for the British North American provinces. As the conflict continued, many European and Canadian observers predicted that the North would lose the war and then invade Canada to compensate for the loss of the Southern states. To this fear were added two clear problems: No Canadian administration had been able to govern for long because the parties were so evenly matched that each election produced a near-deadlock; and Britain, hoping to avoid embroilment in colonial wars, threatened to withdraw the imperial troops. Britain counseled some form of regional union for the North American colonies.

In 1867 the united Canadas (now to be called Ontario and Quebec), Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick formed the Confederation of Canada, to he known as a dominion. Canada was not yet fully independent, but a giant stride toward this goal had been made.

The Canadian confederation added new provinces under the British North America Act of 1867. When British Columbia, which had recently united with Vancouver Island, joined the confederation in 1871, dominion from sea to sea was truly achieved. Thereafter, the interior was progressively settled and new provinces were carved out of the rich agricultural lands. Newfoundland had held aloof from unification, but it voted to join with Canada in 1949.

Meanwhile, Canada had established other precedents by which complete independence from Britain was achieved: the negotiation of a treaty with the United States by which boundary disputes were settled (1871); the creation of its own Department for Foreign Affairs (1909); its assertion of an independent right to sign peace treaties at the end of World War I; its separate membership in the League of Nations (1919); and the removal of any remaining colonial subordination by the Statute of Westminster in 1931. Thus Canada contrasted with the United States, the other predominantly English- speaking North American frontier society, by achieving its independence through evolution rather than revolution.

Dominion status was applied to other colonies of white settlement. The six provinces of Australia had common British origins and relatively short lives as separate colonies, the oldest, New South Wales, dating from 1788. Nevertheless, they developed local differences. They gained the essentials of self-government in the Australian Colonies Government Act of 1850, but federal union and dominion status were not achieved until New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania were linked as the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

The influence of the American example was clear in the constitution of Australia, which provided for a senate with equal membership for each of the six states, a house of representatives apportioned on the basis of population, and a supreme court with certain powers of judicial review. But in Australia, as in the other British dominions, the parliamentary system of an executive (prime minister and cabinet) that could be dismissed by vote of the legislative body was retained.

Long before it became a dominion, Australia pioneered in the secret printed ballot; New Zealand (in 1893) and South Australia (in 1894) extended universal suffrage to women well in advance of Britain and Canada (1918) or the United States (1920).