After 1850 Britain began to lose its advantage. Politically its leaders had positioned it well to the forefront. The Reform Act of 1832 had put Parliament into the hands of the propertied classes, which proceeded to pass legislation favorable to industry.

In 1846 Parliament had repealed the Corn Laws, which had limited the import of grain, and the nation began eighty-five years of nearly tariff-free trade. But the food supply was no longer keeping up, and while the growing empire—the sheep stations of Australia and New Zealand, the vast stretches of prairie in Canada— might meet the need, supplies from nearby Denmark or Holland were obviously cheaper.

With the abolition of the Corn Laws, Britain accepted the principle of heavy specialization, of full commitment to private initiative, private property, and the mechanism of the marketplace. But this also made Britain increasingly dependent on others for certain necessities, so that it had to be able to assure itself of a supply of those necessities by colonial or foreign policy.

As the middle class became more comfortable and the working class more demanding, the possibilities for peaceful innovation free of clashes between management and labor decreased. A period of prolonged inflation, from 1848 to 1873, and another of depression, from 1873 to 1896, intensified the perception of inequalities of wealth between classes and genders and between cities and the countryside. After 1873 British agriculture could no longer compete with that of the Continent or the United States; agriculture began to stagnate, and the overall rate of British growth decreased.

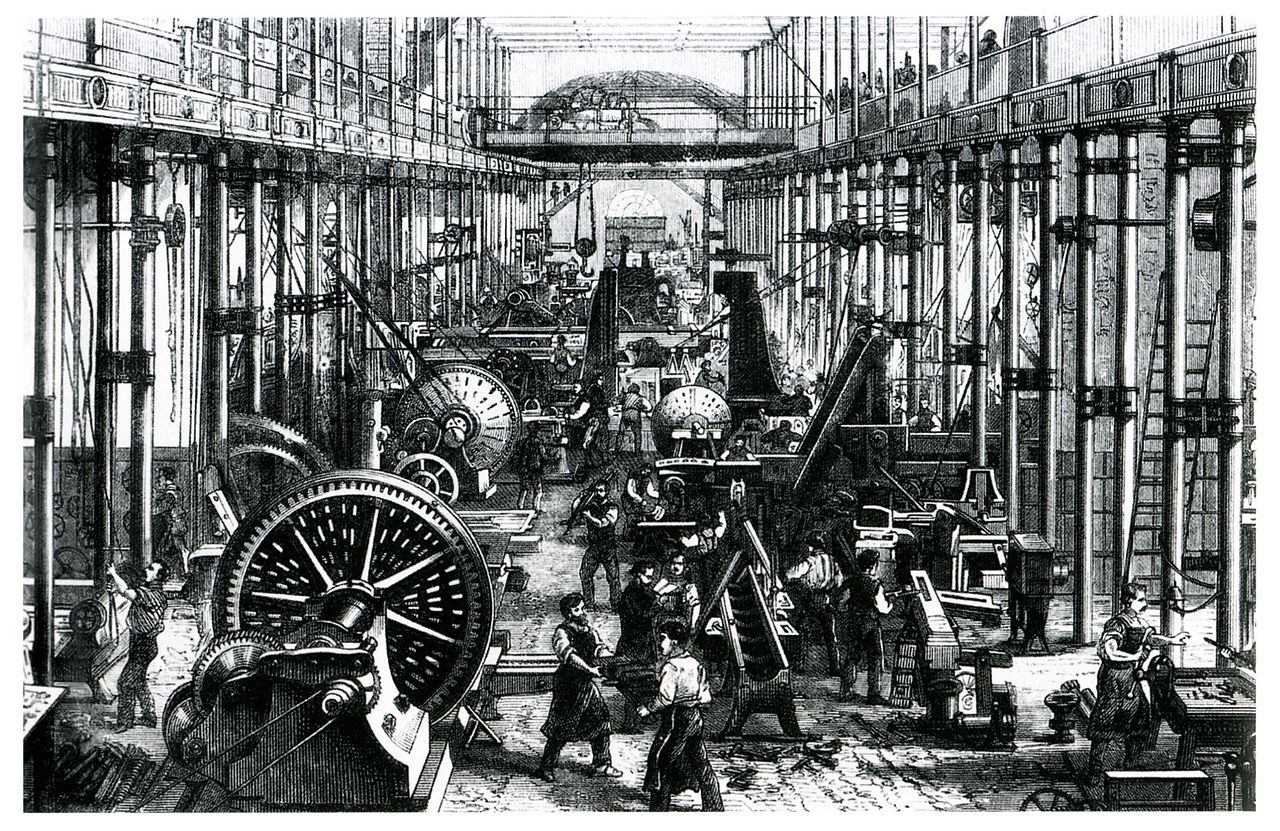

In the new phase of the industrial revolution in Britain, the initial advantage was slowly lost—to Germany, to Belgium, and to the United States. The lead in developing new techniques passed in agricultural machinery to the Americans, in chemical and steel production to the Germans, in electricity to both. England, and particularly London, remained the undoubted financial center of the world, but by 1890 industrial leadership had passed elsewhere.

Industrial and agricultural changes are often mutually dependent. For sustained growth, industry relies on an efficient agriculture for its raw materials and for additions to its labor force, recruited from surplus workers no longer needed on mechanized farms. Agriculture depends on industry for the tools and fertilizers that enable fewer workers to produce more and transform farms into agrarian factories.

In the nineteenth century factory-made implements like the steel plow and the reaper improved the cultivation of old farmlands. The mechanical cream separator raised the dairy industry to a big business, and railroads and steamers sped the transport of produce from farm to market. The processes of canning, refrigeration, and freezing—all industrial in origin and all first applied on a wide scale during the last third of the century—permitted the preservation of many perishable commodities and their shipment halfway around the world.

Farmers found steadily expanding markets both in the industrial demand for raw materials and in the food required by mining and factory towns. International trade in farm products increased rapidly during the second half of the nineteenth century. The annual export of wheat from the United States and Canada rose from 2.2 million bushels in the 1850s to 15 million in 1880. Imported flour accounted for a quarter of the bread consumed in Britain during the 1850s and for half by the 1870s. Denmark and the Netherlands increasingly furnished the British table with bacon, butter, eggs, and cheese; Australia supplied its mutton, and Argentina its beef.

Germany now partly assumed Britain’s old role as the pioneer of scientific agriculture. Shortly after 1800 German experimenters had extracted sugar from beets in commercially important quantities, thus ending Europe’s dependence on the cane sugar of the West Indies. In the 1840s the German chemist Justus Liebig (1803-1873) published a series of influential works on the agricultural applications of organic chemistry. These promoted even wider use of fertilizers: guano from the nesting islands of sea birds off the west coast of South America, nitrate from Chile, and potash from European mines.

The agricultural revolution exacted a price. Faced with the competition of beet sugar, the sugar cane islands of the West Indies went into a depression from which they did not recover. In the highly industrialized countries the social and political importance of agriculture began to decline. The urban merchants and manufacturers demonstrated their dominance in British politics when they won their campaign to abolish the tariffs on grain, which, they said, kept the price of food high. Decisive in the abolition of the Corn Laws in 1846 was an attack of black rot that devastated the Irish potato crop for two years and made it essential to bring in cheap substitute foods.

Meanwhile, across the Channel, France was industrializing far more slowly. Public finance continued to be unstable, capital formation was far more difficult, and France remained wed to tariff protection, which retarded change. Railways were built hesitantly, and the revolution of 1848, caused by an economic crisis, made French financiers even more hesitant.

Agriculture remained especially important, and both farm and city workers in France were reluctant to innovate. An “aristocracy of labor” set crafts workers apart from manual laborers, and some of the working class successfully resisted mechanization. To the inhibitions of small farms and inadequate capital was added the effect of equal inheritance laws, which led to the division of land into tiny parcels so that the peasant could not accumulate capital to take risks on new crops.

Businesses were owned by single families, who could not be protected by limited liability laws or easily recruit new managers. Since bankruptcy had to be avoided above all else, owners could not afford to take risks with new products or new methods. Economic and social conservatism thus limited efforts to create large- scale production or a high degree of specialization.