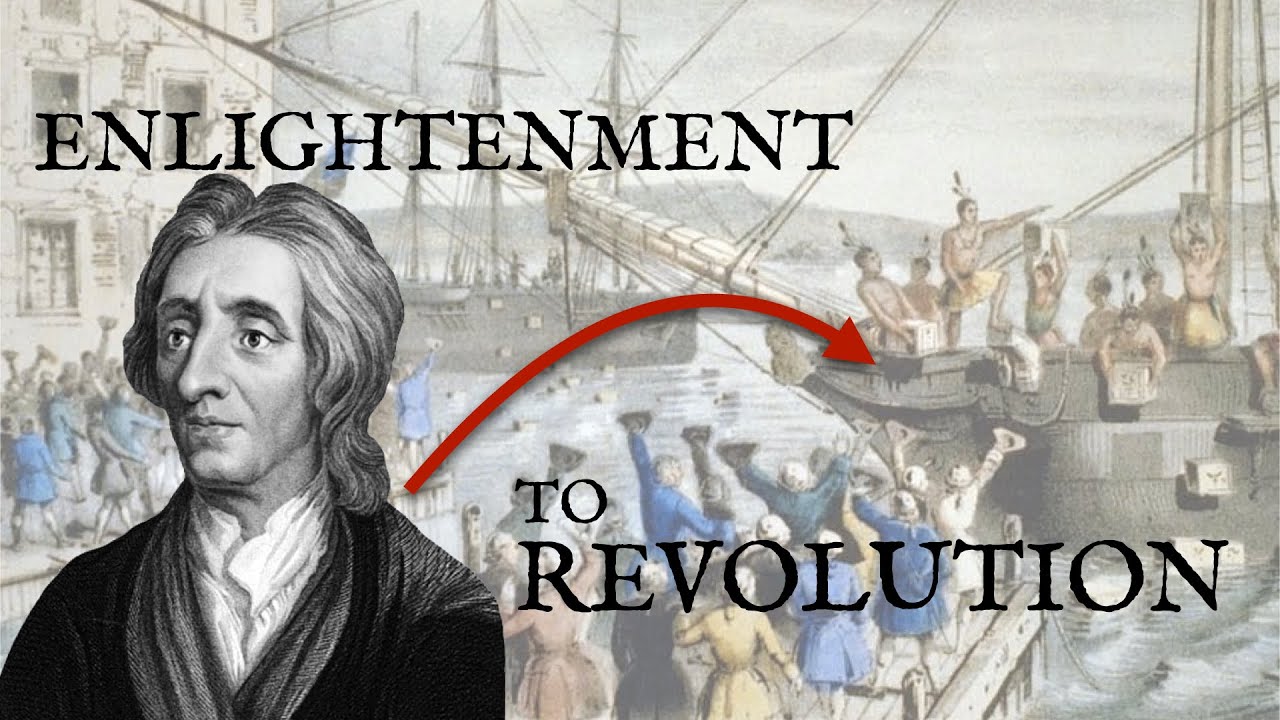

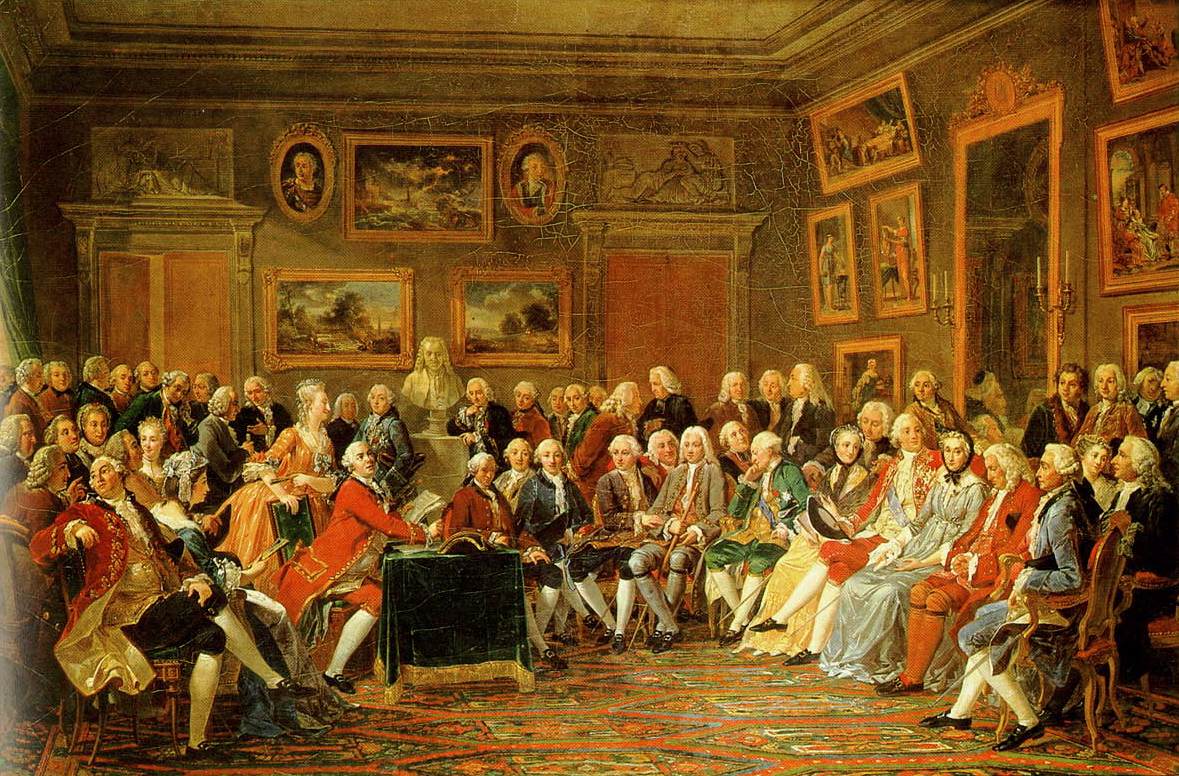

Background of the American Revolt, 1760-1776 | The Enlightenment

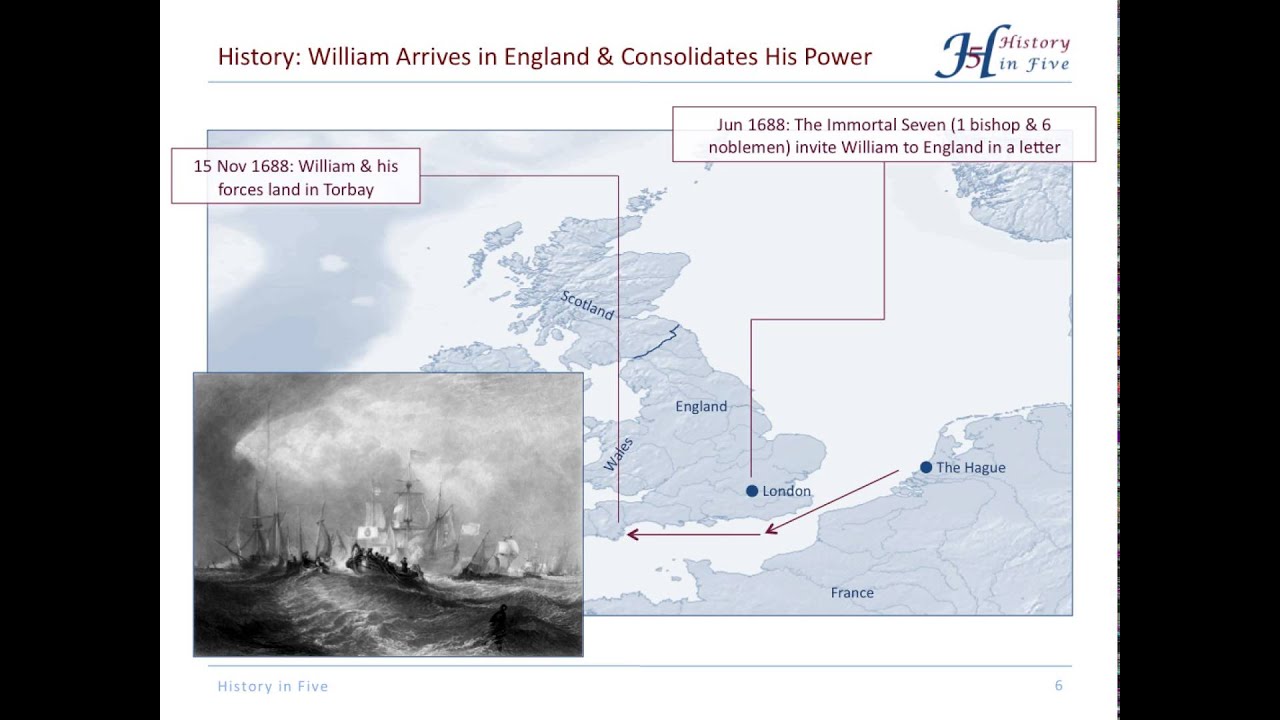

The breach between the colonies and Britain first became serious after the Seven Years’ War, when Britain began to interfere more directly and frequently in colonial matters.

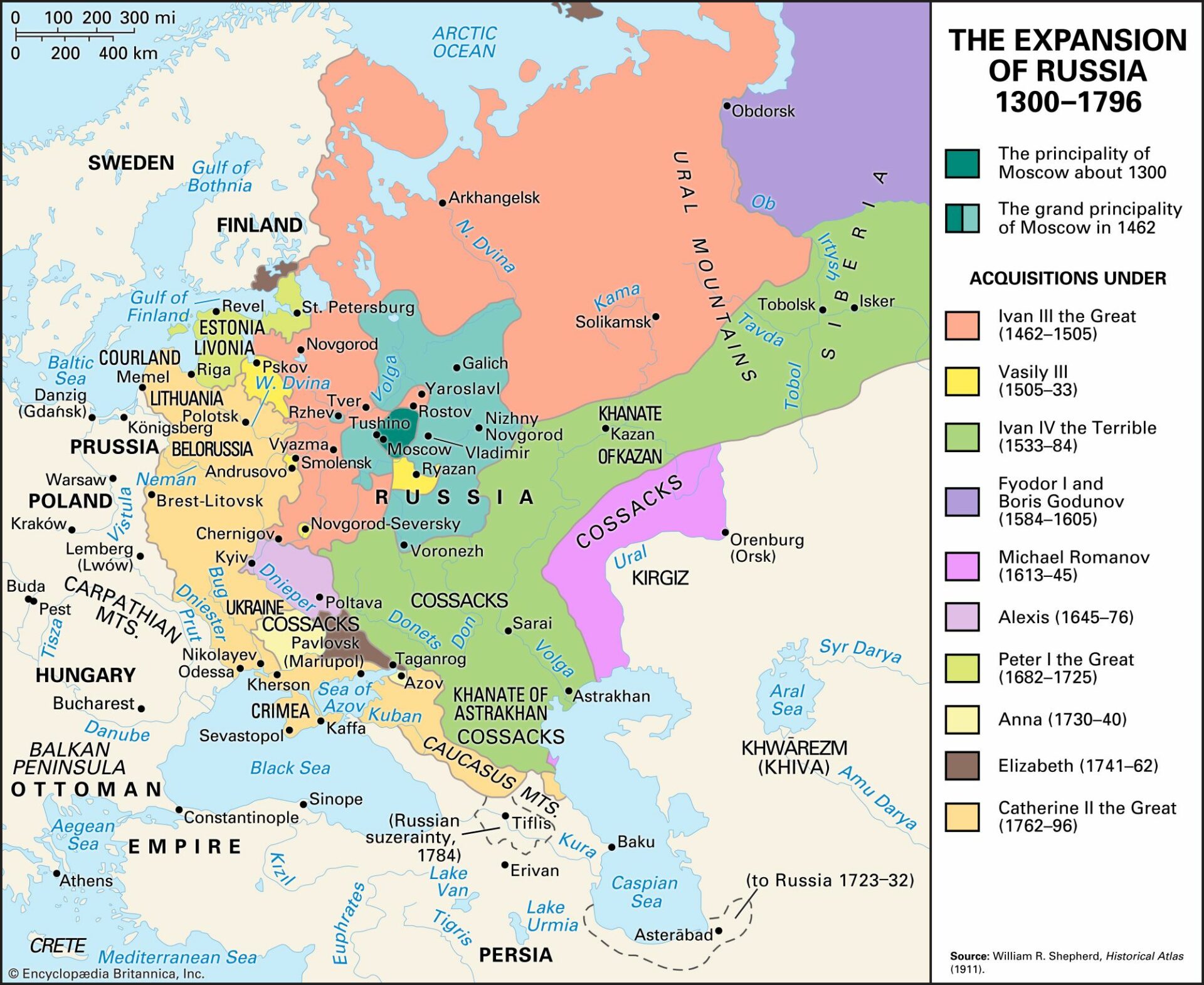

By 1763 the colonies had become accustomed to regulating their own affairs, though the acts of their assemblies remained subject to the veto of royally appointed governors or of the king himself. The vast territories acquired in 1763 in Canada and west of the Allegheny Mountains brought Britain added opportunities for profitable exploitation and added responsibilities for government and defense.