The United States Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1877 | The Modernization of Nations

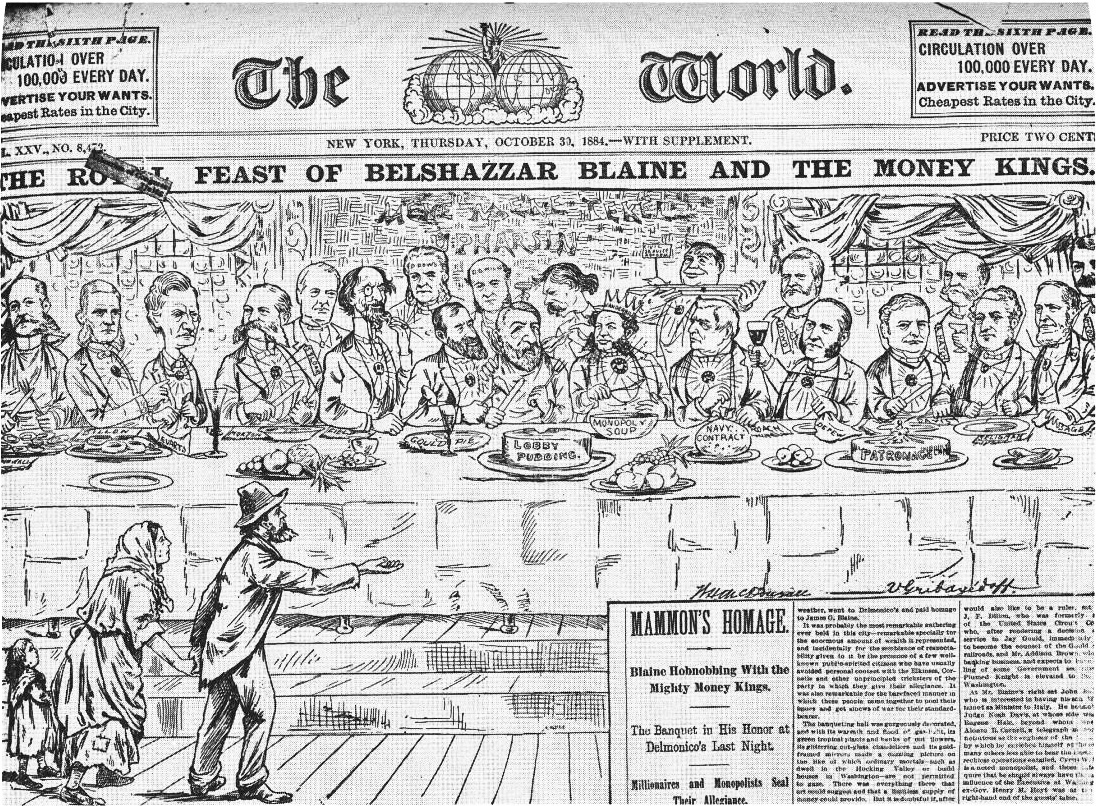

The greatest test of the Federal Union was the war that broke out in 1861 after long years of sectional strife within the union between North and South. The Civil War was really an abortive nationalist revolution, the attempt of the Confederate (Southern) states to set up a separate sovereignty, as the southern Democrats lost political control at the national level.