Octavian was too shrewd to alienate the people of Rome by formally breaking with the past and proclaiming an empire. He sought to preserve republican forms, but also to remake the government along the lines suggested by Caesar. After sixty years of internal strife, the population welcomed a ruler who promised order.

Moving gradually, and using his huge personal fortune—now enlarged by the enormous revenues of Egypt—Octavian paid for the pensions of his own troops and settled over one hundred thousand of them on their own lands in Italy and abroad. He was consul, inzperator (a military-style emperor), and soon governor in his own right of Spain, Gaul, and Syria. He was princeps (first) among the senators. In 27 B.C. the Senate gave him the new title of Augustus (revered one), by which he was thereafter known to history, although he always said his favorite title was the traditional one of princeps, and his regime is called the Principate.

Augustus had far more power than anybody else, but in 23 B.C. the Senate gave him the power of a tribune—the power to veto and the right to introduce the first measure at any meeting of the Senate. As censor he reduced the membership of the Senate in 29 B.C. from one thousand to eight hundred members, and in 18 B.C. from eight hundred to six hundred. As senators, he appointed men he thought able, regardless of their birth. He created a civil service where careers were open to talent. Having endowed a veterans’ pension department out of his own pocket, he created two new taxes—a sales tax of one-hundredth and an estate tax of one-twentieth to support it. He initiated the most careful censuses known to that time. His social laws made adultery a crime and encouraged larger families.

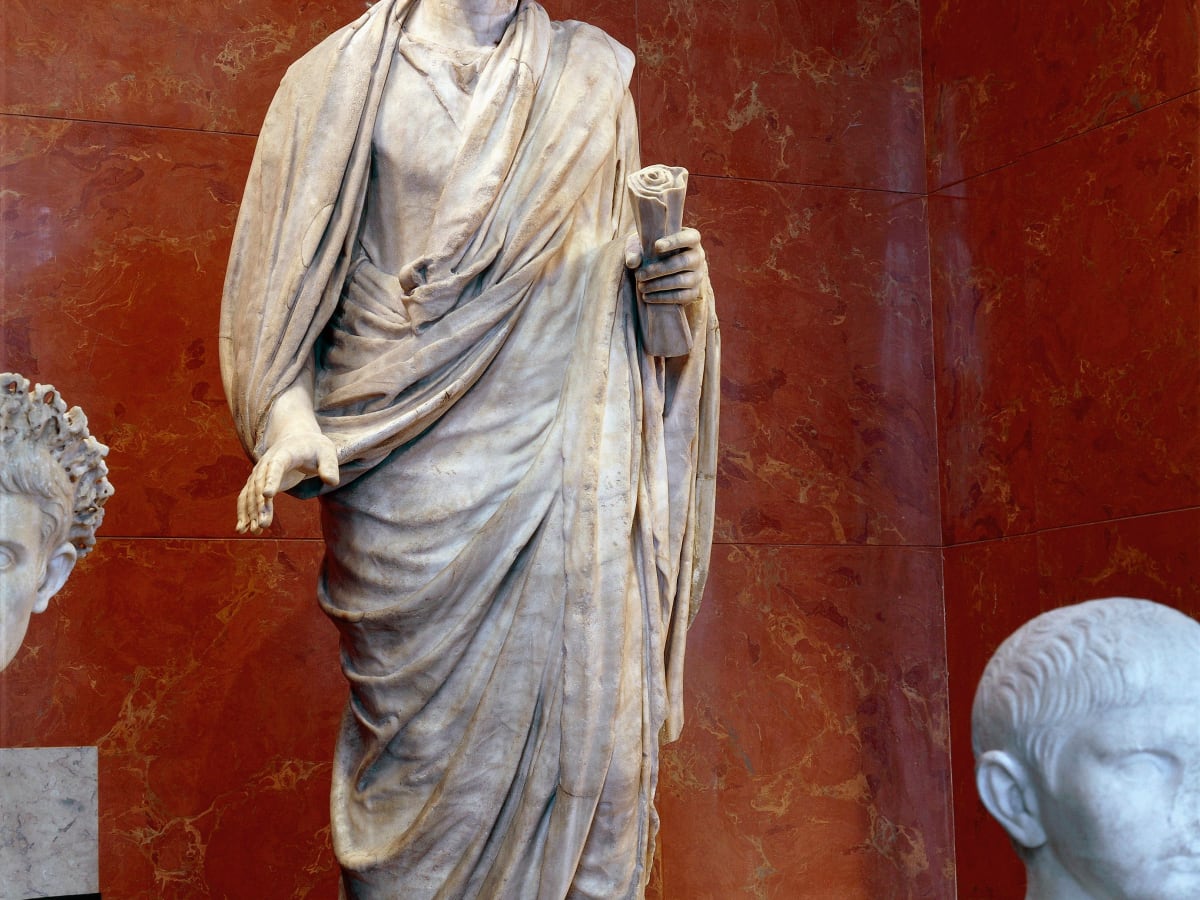

Augustus wished, as he said, to turn Rome from a city of brick to a city of marble. He built or restored eighty-two temples in a single year, and the populace was benefited by unprecedented growth in amphitheaters, baths, basilicas, temples and forums. Architects and engineers produced magnificent, innovative structures, improved roads throughout Italy, and developed the first extensive use of concrete. The popularity of marble led to the need for Greek craftsmen, however. Roman taste (and money), wedded to Greek skills and ideas, led to some of the most noted buildings of antiquity. Augustus also gave Rome its first police and fire departments.

Aided by the growing network of new roads, the army—which at one point numbered about 400,000 men—occupied permanent garrison camps on the frontiers. In peacetime the troops worked on public projects such as aqueducts or canals. The legions were made up of Roman citizens who volunteered to serve and who retired after twenty-six years’ service with a bonus equal to about fourteen years’ salary. Non-citizens in somewhat lesser numbers served as auxiliaries, becoming citizens after thirty years of service. Augustus also created the Praetorian Guard: nine thousand specially privileged and highly paid troops, of whom about one third were regularly stationed in Rome.

In the East, Augustus reached a settlement with the Parthians and thus probably averted an expensive and dangerous war. In 4 B.C. Herod, the client king of Judea, died, and the Romans henceforth ruled the country through a Roman procurator, who resided outside Jerusalem as a concession to the Jews. Jews retained their freedom of worship, did not have to serve in the Roman armies, and did not have to use coins bearing “graven images”—the portrait of Augustus. Under Augustus most of Spain was pacified, and the Romans successfully administered Gaul. Roman power was extended in what is now Switzerland and Austria and eastward along the Danube into present- day Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Bulgaria, to the Black Sea.

But in A.D. 9* the Roman armies suffered a disaster in Germany. A German chief named Hermann—who had served in the Roman army, became a Roman citizen and had his name translated as Arminius—turned against Rome and ambushed the Roman armies, wiping out three full legions at the battle of the Teutoburger Forest. Now an old man and increasingly distrustful of foreign adventures, Augustus made little effort to avenge the defeat. The Rhine River frontier proved to be the final limit of Roman penetration into north-central Europe.

The Roman provinces were now probably better governed than under the Republic. Certainly, and despite occasional slave uprisings and violence in the countryside, the early Roman Empire was orderly and relatively stable economically. Regular census taking permitted a fair assessment of taxes. In Gaul the tribes served as the underlying basis for government; in the urbanized East the local cities performed that function. Except for occasional episodes, Augustus had done his work so well that the celebrated Pax Romana (the Roman Peace) lasted from 27 B.C. until A.D. 180—more than two hundred years.

When Augustus died in A.D. 14, the only possible surviving heir was his stepson, Tiberius, son of his wife Livia by her first husband. Gloomy and bitter, Tiberius reigned until A.D. 37, emulating Augustus during the first nine years but thereafter becoming preoccupied with the efforts of Sejanus, commander of the Praetorian Guard, to secure the succession to the throne. Absent from Rome for long periods and in seclusion on the isle of Capri, Tiberius became extremely unpopular, even though he reduced taxes and made interest-free loans available to debtors.

Ultimately, he recognized the threat to his authority posed by Sejanus, whom he executed in 31. About two years later his procurator in Judea, Pontius Pilate, allowed the execution by crucifixion of Jesus, who called himself “the Anointed” (in Greek, Christos), because this Messianic claim was considered seditious. Tiberius’s grandnephew and successor, Caligula (r. 37-41), was perhaps insane and certainly brutish. The number of irrational executions mounted, and the emperor enriched himself with the property of his victims. Caligula was assassinated in A.D. 41.

Caligula’s uncle Claudius (r. 41-54) was a learned student of history and languages who strove to imitate Augustus by restoring cooperation with the Senate. He added to the size and importance of the bureaucracy by dividing his own personal staff into regular departments or bureaus. As a result, the imperial civil service made great strides in his reign. Claudius was also generous in granting Roman citizenship to provincials. Abroad, he added to Roman territory in North Africa, the Balkans, and Asia Minor. And in A.D. 43 he invaded Britain, ninety-eight years after Julius Caesar’s first invasion. Southeast England became the province of Britain, whose frontiers were pushed outward toward Wales. But the conspiracies of his fourth wife, Agrippina, to obtain the succession for Nero, her son by an earlier marriage, culminated in her poisoning Claudius in 54. Agrippina herself was murdered by Nero in 59.

Although dissolute, Nero (r. 54-68) did not start the great fire that burned down much of Rome in 64. Indeed, he personally took part in the efforts to put the fire out and did what he could for those who had been left homeless. But the dispossessed did blame him for incompetence, and to find a scapegoat he accused the new sect of Christians. Their secret meetings had led to charges of immorality, and Nero persecuted them to distract attention from himself.

There were serious revolts in Britain in 61, led by Queen Boadicea. She was “huge of frame, terrifying of aspect, with a harsh voice. A great mass of bright red hair fell to her knees; she wore a great twisted golden torc [neck ring], and a tunic of many colors, over which was a thick mantle fastened by a brooch. “She grasped a spear, and terrified all who saw her,” a Roman historian reported.

But the chief threat in the provinces arose in Judea. Only a small upper class supported Roman rule, and the Romans had too few troops to keep order. In 66, after the Jewish high priest refused to sacrifice to Jehovah for the benefit of Nero and a group of Jewish zealots massacred a Roman garrison, there was open warfare. Faced with rebellion in Spain and in Gaul, and unable to control his armies, Nero was displaced by the Senate, and in 68 he committed suicide.