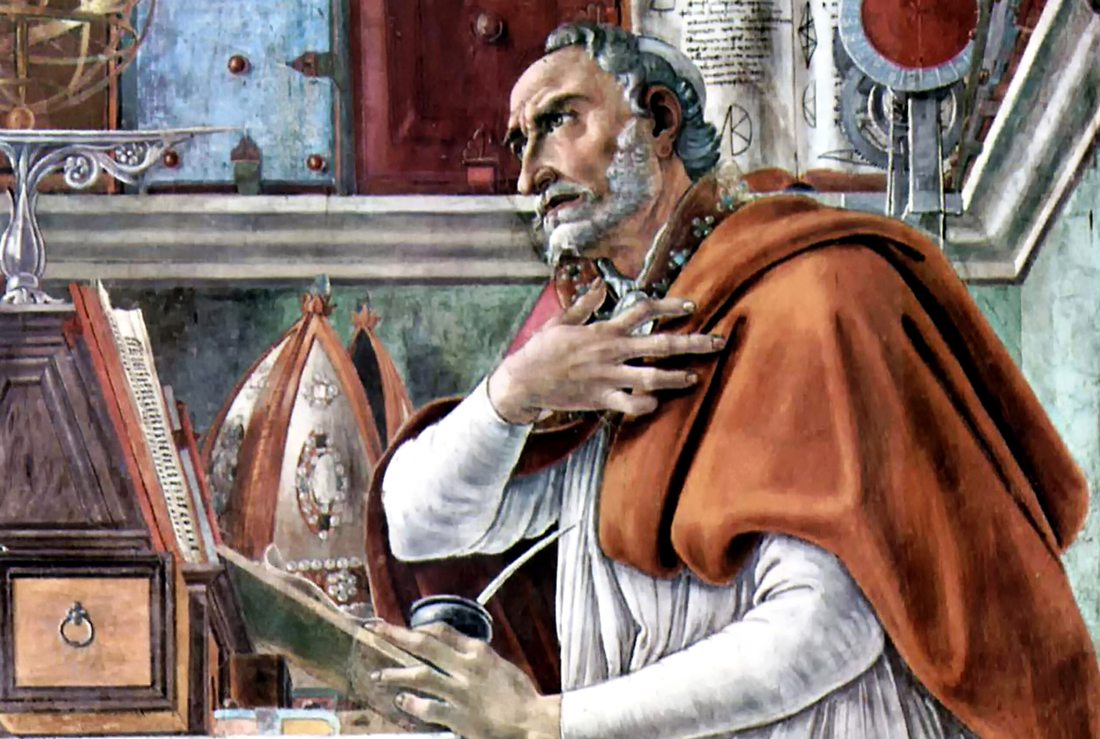

We know Augustine (354-430) intimately through his famous autobiography, The Confessions. He was born in a small market town in what is now Algeria, inland from Carthage, the administrative and cultural center of the African provinces. Here the population still spoke Punic (Phoenician), but the upper classes were Latin speaking, wholly Roman in their outlook, and deeply imbued with the classical traditions of Rome. Prosperous planters lived on their great estates, while peasants toiled in the fields and olive groves.

Of modest means and often at odds with one another, Augustine’s father and his devoutly Christian and possessive mother were determined that he should be given a good education, for this was the path to advancement. But all that his teachers did was force him to memorize classical Latin texts and to comment on them in detail. Augustine was so bored that he never did learn Greek, and so was cut off from the classical philosophers and forced to pick up their ideas at second hand. His parents’ ambitions for him prevented him from getting married at seventeen, like most of his contemporaries. While at school, Augustine took a concubine, with whom he lived happily for fifteen years and by whom he had a son.

Disappointed with his reading of the Bible, which he found insufficiently polished and too confining, Augustine at nineteen joined the Manichaeans. The sect was regarded by pagans and Christians alike as subversive and had been declared illegal. Gone were Augustine’s plans to become a lawyer, as his mother had wished; he determined to learn and teach the Manichaean “wisdom.”

When he went back to his birthplace, his mother was so angry with him for having become a Manichaean that she would not let him into the house. But the static quality of Manichaean belief, the naive(82 of its rituals, and the disappointing intellectual level of its leaders began to disillusion Augustine, and he returned to Carthage to teach rhetoric. Highly placed friends invited him to move to Italy. At twenty-eight he was appointed professor of rhetoric at Milan, the seat of the imperial court. The job required him to compose and deliver the official speeches of praise for the emperor and for the consuls—propaganda for the official programs.