American revulsion against war also took the form of isolationism, the wish to withdraw from international politics outside the Western Hemisphere. The country was swept by a wave of desire to get back to “normalcy,” as President Warren Harding phrased it.

Many Americans felt that they had done all they needed to do in defeating the Germans, and that further participation in the complexities of European politics would simply involve American innocence and virtue even more disastrously in European sophistication and vice. As the months of negotiation went on in Europe with no final decisions, many Americans began to feel that withdrawal was the only effective action they could take. The Treaty of Versailles, containing the establishment of the League of Nations, was finally rejected in the Senate on March 19, 1920.

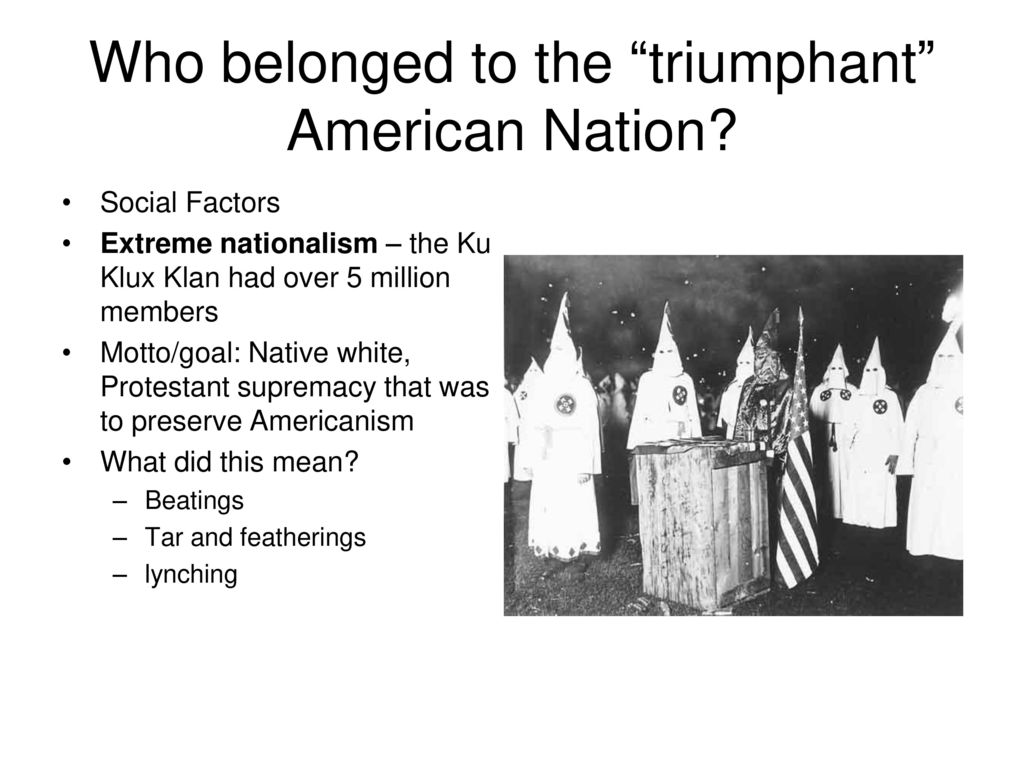

American isolationism was also expressed in concrete measures. Tariffs in 1922 and 1930 set successively higher duties on foreign goods and emphasized America’s belief that its high wage scales needed to be protected from cheap foreign labor. The spirit of isolationism, as well as growing racist movements, also lay behind the immigration restrictions of the 1920s, which reversed the former policy of almost unlimited immigration.

The reversal was hastened by widespread prejudice against the recent and largely Catholic and Jewish immigrations from southern and eastern Europe. The act of 1924 set an annual quota limit for each country of 2 percent of the number of nationals from that country resident in the United States in 1890. Since the heavy immigration from eastern and southern Europe had come after 1890, the choice of that date reduced the flow from these areas to a trickle. Northern countries like Britain, Germany, and the Scandinavian states, on the other hand, did not use up their quotas.

Isolationism did not apply to all matters, however. The United States continued all through the 1920s to insist that the debts owed to it by the Allied powers be repaid. Congress paid little heed to the argument. so convincing to most economists, that the European nations could not repay except with dollars gained by selling their goods in the American market, and that American tariffs continued to make such repayment impossible.

Yet the United States did not withdraw entirely from international politics. Rather, as an independent without formal alliances, it continued to pursue policies that seemed to most Americans traditional, but that in their totality gradually aligned them against the rising dictatorships. In 1928 the Republican secretary of state, Frank B. Kellogg (1856-1937), proposed that the major powers renounce war as an instrument of national policy.

Incorporated with similar proposals by the French foreign minister, Aristide Briand (1862-1932), it was formally adopted that year as the Pact of Paris, commonly known as the Kellogg-Briand Pact, and was eventually signed by twenty-three nations. Although the pact proved ineffective, the fact that it arose in part from American initiative and that the United States was a signatory to it, was clear indication that even if Americans did not wish to enter into any formal alliances, they were still concerned with the problems of worldwide stability and peace.

During the 1920s the United States was hard at work laying the foundations for the position of world leadership it reached after World War II. American businesses were everywhere; American loans were making possible the revival of German industry; American motors, refrigerators, typewriters, telephones, and other products were being sold the world over.

In the Far East the United States led in negotiating the Nine-Power Treaty of 1922 that committed it and the other great powers, including Japan, to respect the sovereignty and integrity of China. When Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt resisted the Japanese attempt to absorb China and other Far Eastern territory, he was following a line laid down under his Republican predecessors.