The rebellion against imperialism reached Africa in the 1950s. Ethiopia was taken from its Italian conquerors after World War II and restored to Emperor Haile Selassie, who had been ousted in 1936.

In 1952 he annexed the former Italian colony of Eritrea. Selassie embarked on various programs of internal modernization though not liberalization, and he worked hard to assist in the development of the Organization of African Unity. However, he misjudged both the speed and the nature of his reforms.

An army mutiny, strikes in Ethiopia’s cities, and massive student demonstrations in the capital, Addis Ababa, led to his imprisonment in 1974. The military junta then turned to local Marxists and the Soviet Union for support. In 1978 Soviet advisers and twenty thousand Cuban troops helped rout a Somalian independence force; in the same year a famine took an estimated million lives.

Governed by a provisional military administrative council, Ethiopia was clearly far worse off in the 1980s than it had been under Selassie. Widespread famine and bloody civil war destroyed the nation’s fragile economy, and in May 1991 its communist dictator fled the country in the face of an impending rebel victory. In 1993 Eritrea declared itself independent once again.

Particularly unpredictable was the unstable nature of Somalia, a nation on the Horn of East Africa formed from Italian and British colonial holdings in 1960. A bloodless coup in 1969, led by a Supreme Revolutionary Council, began a chaotic series of changes.

Somalia claimed the Ogaden from Ethiopia on the ground that it was populated largely by ethnic Somalis, and Ethiopia turned to Soviet arms and Cuban troops to drive out the Somalian troops in a war that lasted until 1988 and brought 1,500,000 refugees into the already impoverished Somalian republic. One-man rule ended in 1991, but civil war, drought, and growing lawlessness took 40,000 lives in the next two years and the refugees faced starvation.

In July 1992 the UN took the unusual action of declaring Somalia to be a nation without a government; the United States offered to send troops to safeguard food deliveries to the starving. In the face of casualties and further chaos, the United States withdrew its troops in March 1994, though some UN forces stayed to protect the distribution of relief aid. Violence continued, and Somalia remained without a viable government.

Among the Muslim and Arabic-speaking states bordering the Mediterranean, the former Italian colony of Libya achieved independence in 1951, and the French-dominated areas of Morocco and Tunisia in 1956. Morocco became an autocratic monarchy and Tunisia a republic under the moderate presidency of Habib Bourguiba (1903– ). Algeria followed, but only after a severe and debilitating war of independence against the French.

Its first ruler after independence, Ahmed Ben Bella (1918– ), was allied with the Chinese communists. Colonel Houari Boumedienne (1925-1981), who ousted Ben Bella in 1965, in large part because of the slumping economy, favored the Soviets. Algeria and Libya strongly supported the Arab cause against Israel; Morocco and Tunisia did so hardly at all, though Tunis did become the headquarters for the Arab League in 1979.

In 1987 Bourguiba was deposed, and his successors systematically repressed Islamic fundamentalism. Algeria was less successful in doing so, and an ambitious intention to establish a multiparty system was abandoned when, in 1992, the government canceled national elections in the face of a likely Islamic fundamentalist victory.

The president was assassinated, and over the following years security forces, foreigners, high-ranking officials, and intellectuals were killed by the fundamentalists while, in turn, the state took thousands of lives in its drive to end the insurgency. By 1995 the assassinations were being carried into France, which supported the government’s hard line, while other Western powers urged conciliation, leading to a rift that the fundamentalists clearly hoped to capitalize upon.

In Libya a coup d’etat in 1969 brought to power a group of army officers. In 1970 they confiscated Italian and Jewish-owned property. American evacuation of a huge air base in Libya and Libyan purchases of French and Soviet arms added to the general apprehension in North Africa. A temporary “union” of Egypt, Libya, and the Sudan in 1970 had little political importance, but it marked the emergence of Colonel Muammar el-Qaddafi (1942– ), the Libyan political boss and prime minister, as the most fanatic Muslim fundamentalist and most dictatorial ruler in the Arab world.

He was also one of the richest, and he used his oil riches to instigate rebellion and political assassination throughout the Arab world. After 1975 he purchased billions of dollars worth of modern Soviet arms and became the supplier to terrorist groups in much of the world. Mercurial and unpredictable, Qaddafi waged border wars against Egypt in 1977 and in Chad from 1977. In 1980 he conscripted civil servants into his army, casting the economy into chaos and paralyzing administration.

Even so, he continued to command a widespread loyal following, perhaps in part because of American air and sea attacks on Libya in 1986. In 1992 the UN imposed sanctions on Libya for its failure to surrender men believed to be linked to the bombing in 1988 of an American commercial aircraft over Lockerbie, Scotland, but Qaddafi remained in power.

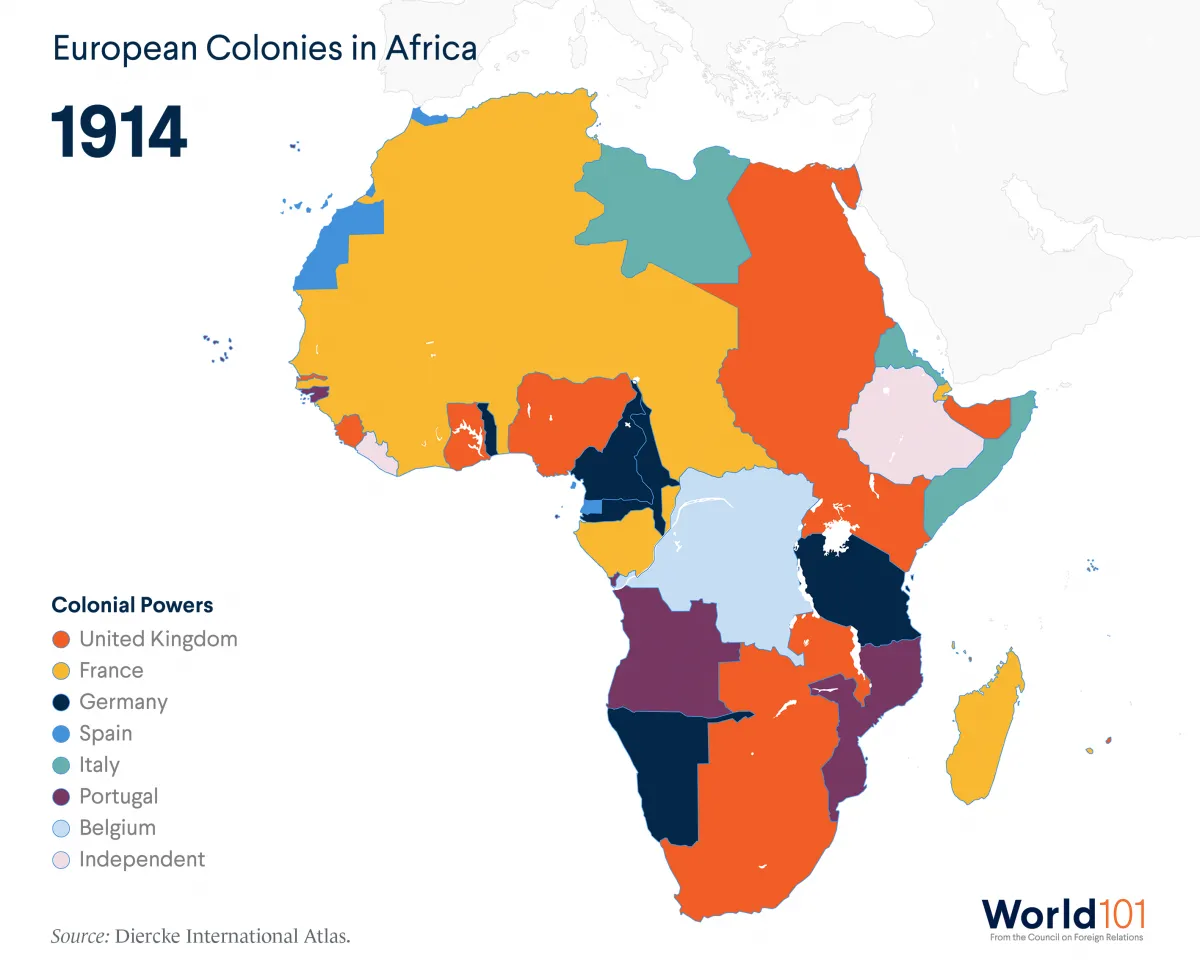

South of the Muslim tier of nations lay the former colonies of the French, British, and Belgians. The West African climate had discouraged large-scale white settlement, except in portions of the Belgian Congo; but in East Africa—in Kenya and Uganda especially—many Europeans had settled in the fertile highlands, farmed the land, and regarded the country as their own, as did the large white population of the Union of South Africa. Here, too, were substantial Indian populations, usually small merchants, who carried on trade across the Indian Ocean.

In the areas with little white settlement, independence came quickly. The Gold Coast, with a relatively well-educated population and valuable economic resources, became the nation of Ghana in 1957. Its leader, the American-educated Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972), made a hopeful start on economic planning within a political democracy. But he grew increasingly dictatorial, jailing his political enemies and sponsoring grandiose projects that personally enriched him and his followers.

A promising democracy became a dictatorship in the 1960s, while the economy was in serious disarray. Rising foreign debt and Nkrumah’s inability to persuade the rich and populous Asante people to submerge themselves in a greater Ghanaian nationalism, led to his overthrow by a military coup early in 1966. Many coups later, however, Ghana remained economically stagnant and overpopulated.

The French colonies all achieved independence in 1960, except for Guinea, which broke away in 1958 under the leadership of a pro-Soviet, Ahmed Sekou Toure (1922-1984). After independence, most of the colonies retained close economic ties with France as members of the French Community. Guinea did not; the French left in 1958, and the country developed a socialist economy with some success. The neighboring states of Mali (formerly French Sudan) and Mauritania also pursued a generally pro-Soviet line.

Of the newly independent former French colonies, two proved especially important. Senegal grew under the twenty-year leadership of Leopold Senghor (1906– ), a noted poet who spoke of the beauties of negritude, helping give rise to the slogan “black is beautiful” around the world. The Ivory Coast, whose leader Felix Houphouet Boigny (1905-1993) had long parliamentary experience as a deputy in Paris, also proved to be stable and prosperous. The Ivory Coast led a pro-Western bloc within the Organization of African Unity, while Senegal often played the role of intermediary between factions, developing a multiparty system and full democratic elections at home.

In 1960 Nigeria, most important of the British colonies, achieved independence. With 60 million people and varied economic resources, it represented a great hope for the future. The British had trained many thousands of Nigerians in England and in schools and universities in Nigeria itself. The country was divided into four regions, each semi autonomous, to ease tribal tensions, of which perhaps the most severe was that between the Muslim Hausa of the northern region and the Christian Ibo of the eastern region. In the Hausa areas, the well educated, aggressive, and efficient Ibos ran the railroads,

power stations, and other modern facilities, and formed an important element in the cities. When army plotters led by an Ibo officer murdered the Muslim prime minister of Nigeria and seized power in 1966, the Hausas rose and massacred the Ibos living in the north, killing many thousands.

By 1967 the Ibo east had seceded and called itself the Republic of Biafra, and the Nigerian central government embarked on full-scale war to force the Ibos and other eastern groups to return to Nigerian rule. Misery and famine accompanied the operations, and the war dragged on until 1970, with both Britain and the Soviet Union helping the Nigerian government. The Biafrans got much sympathy but no real help.

When the war finally ended, the mass slaughter that had been feared did not materialize and the nation devoted its energies to reconciliation and recovery. Nigeria was able to use its growing oil revenues for economic development. In 1979 it returned to civilian government after thirteen years of military rule, but in 1983 a coup ended democratic government.

In east Africa, the British settlers in Kenya struggled for eight years (1952-1960) against a secret terrorist society formed within the Kikuyu tribe, the Mau Mau, whose aim was to drive all whites out of the country. Though the British imprisoned one of its founders, Jomo Kenyatta (1893-1978), and eventually suppressed the Mau Mau, Kenya became independent in 1963. Kenyatta became its first chief of state and steered Kenya into prosperity and a generally pro-Western stance. However, Kenya moved increasingly toward authoritarian government under Kenyatta’s successor, Daniel Arap Moi (1924— ). In 1961, under the leadership of Julius Nyerere (1922— ), Tanganyika became independent.

A violent pro-Chinese communist coup d’etat on the island of Zanzibar was followed in 1964 by its merger with Tanganyika as the new country of Tanzania. Nyerere solicited assistance from Communist China to build the Tanzam railroad from Dar es Salaam, the Tanzanian capital, to Zambia, to help that new nation achieve greater economic independence from South Africa. Nyerere also nationalized the banks, established vast new cooperative villages to stimulate more productive agriculture, and sought to play a major role in holding African nations to a neutralist course. Still, all efforts to create an East African federation failed, as Kenyatta pursued a generally capitalist path, Nyerere a socialist one, and Uganda an intensely nationalist and isolationist policy.

In contrast to the British, who had tried to prepare the way for African independence by providing education and administrative experience for Africans, the Belgians, who had since the late nineteenth century governed the huge central African area known as the Congo, had made no such effort. When the Belgian rulers suddenly pulled out in 1960, it was not long before regional rivalries among local leaders broke out. A popular leftist leader, Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961), was assassinated; the province of Katanga, site of rich copper mines and with many European residents, seceded under its local leader, who was strongly pro-Belgian; other areas revolted.

The United Nations sent troops to restore order and force the end of the Katangese secession, while the Chinese supported certain rebel factions and the South Africans and Belgians others. By 1968 the military regime of General Joseph Mobutu (1930— ) was firmly in control. Soon after, Mobutu renamed the cities and people of his country to erase all traces of the colonial past: the Congo became Zaire, and he changed his own name to its African form, Mobutu Sese Seko.

Two small Belgian enclaves, originally under German control from 1899 and administered by the Belgians as a League of Nations mandate from 1916 and a UN trusteeship after World War II, also experienced civil war. Originally Ruanda-Urundi, the two areas became Rwanda and Burundi in 1962. The Hutu people were in a substantial majority in both states, though they were ruled by the Tutsi, who took the best positions in government and the military.

An unsuccessful Hutu rebellion in Burundi in 1972-1973 left 150,000 Hutu dead and propelled 100,000 refugees into Zaire and Tanzania. The first democratic election in Burundi, in 1993, was followed by the assassination of the elected Hutu leader, resulting in waves of ethnic violence. In April 1994 the presidents of both Burundi and Rwanda were killed in an unexplained plane crash, and systematic massacres followed, especially in Rwanda.

Hutu militias killed over 200,000 Tutsi, and 2 million refugees fled to miserable camps in Zaire and elsewhere, where cholera decimated the starving populations. French troops, acting for the UN, moved in to establish a “safe zone,” but the inter-ethnic strife, and the fact that many Roman Catholic clergy had been killed in the predominantly Christian country, left deep wounds and simmering suspicion even as the French gave way to an African peacekeeping force later in the year.

In Portuguese Angola a local rebellion forced Portuguese military intervention. Angola, which provided Portugal with much of its oil, together with Mozambique on the east coast and the tiny enclave of Portuguese Guinea on the west, remained under Lisbon’s control despite guerrilla uprisings. The Portuguese regarded these countries as overseas extensions of metropolitan Portugal. But the guerrilla war proved expensive and unpopular at home, and in the mid-1970s Portugal abandoned Africa. Thereafter Angola became a center for African liberation groups aimed at South Africa. The Angolan government invited in many thousands of Cuban troops, to the dismay of the United States, and the remained until 1991.

Most stubborn of all African problems was the continuation and extension of the policy of apartheid in South Africa, where whites were a minority of about one in five of the population. The nonwhites included blacks, coloureds (as those of mixed European and African ancestry were called), and Asians, mostly Indians.

The Afrikaners, who had tried unsuccessfully to keep South Africa from fighting on Britain’s side in World War II, had emerged after the war as a political majority. Imbued with an extremely narrow form of Calvinist religion that taught that God had ordained the inferiority of blacks, the ruling group moved steadily to impose policies of rigid segregation: separate townships to live in, separate facilities, no political equality or inter-marriage, little opportunity for higher education or advancement into the professions, and frequent banning of black leaders.

The Afrikaners also introduced emergency laws making it possible to arrest people on suspicion, hold them incommunicado, and punish them without trial. Severe censorship prevailed, and dissent was curbed. In 1949, in defiance of the United Nations, South Africa annexed the former German colony and League mandate of Southwest Africa, where the policy of apartheid also prevailed. The International Court of Justice in 1971 ruled that South Africa was holding the area illegally.

One possible solution to the Afrikaner problem— how to maintain segregation, prevent rebellion by the black majority, assure South Africa of a continuing labor force, and satisfy world opinion—seemed to be a combination of modest liberalization of the apartheid laws and the establishment of partially self-governing territories, known as Homelands, to which black Africans would be sent.

Begun in 1959 as Bantustans, or “Bantu nations,” the plan called for pressing most blacks onto 13 percent of the country’s land area. Virtually no African nation would support such a plan, and much of the West was also opposed. The United States equivocated.

It saw South Africa as a strategically important potential ally in case of war with the Soviet Union and appreciated its staunch anticommunist position on world affairs, but it also realized that any unqualified support to the South African regime would cost the United States nearly the whole of black Africa and would also be opposed by many at home. Thus when South Africa finally created its first allegedly independent Homelands—the Transkei in 1976, Bophuthatswana and Ciskei in 1977, and Venda in 1979—not one nation, including the United States, gave them diplomatic recognition.

Despite South Africa’s most efficient and well equipped military force, and the very competent Bureau for State Security (mockingly called BOSS), the apparently secure, white-dominated government was repeatedly challenged by black youth, a rising labor movement, and the African National Congress which, in 1983, turned to terrorism. International condemnation of South Africa did not appear to shake the determination of the government of P. W Botha (1916– ) to maintain white supremacy.

In 1989 Botha stepped down and was succeeded by F. W de Klerk (1936– ), who had committed himself to phasing out white domination, though without permitting black majority rule. De Klerk surprised the world by doing as he had promised, and at the cost of the withdrawal of several members of his Nationalist party, he ended many of the segregated practices and, early in 1991, declared before parliament that full racial equality was his goal. The many nations that had applied economic sanctions against South Africa to force change now felt vindicated, as apartheid appeared to be near an end.

Two black African leaders who had opposed each other also appeared to have made their peace early in 1991. Nelson Mandela (1918– ), in particular, became a worldwide symbol of hope for racial harmony in southern Africa. Until the Sharpeville massacre of 1960 he had been an advocate of nonviolence and a vice-president of the African National Congress (ANC), but when he turned to sabotage he was imprisoned for life in 1964.

From prison he became the rallying point for the South African freedom movement. Botha offered Mandela his freedom subject to a promise not to use violence to achieve change, and Mandela refused; in February 1990, de Klerk released him unconditionally. After a triumphant trip to the United States and elsewhere, Mandela returned to South Africa to attempt to create a unity movement.

The leader of the most prominent tribe, the Zulu, was Gatsha Buthelezi (1928– ), who favored negotiation with the white government and was believed to be angling for Zulu dominance in any multiracial administration that might result. At times Buthelezi had openly opposed the ANC, and the Inkatha Movement, which he led, fomented street fighting in black communities throughout the 1980s. However, with Mandela’s release and de Klerk’s denunciation of apartheid, Buthelezi agreed to work with Mandela and the ANC.

Despite repeated outbreaks of local violence, the transition to full democracy was far smoother than virtually any observers had predicted. In 1993 the ANC and the National Party agreed on the outline of a new constitution, and in April 1994 South Africa held its first election in which people of all races could vote. Mandela became president, the ANC taking over 62 percent of the vote. The last legal vestiges of racial separation were cast down.