One more empire was being formed during the decades before World War I, the only modern empire to be created by a non-European people. Even during their long, self-imposed isolation the Japanese had maintained an interest in Western developments.

When Japan opened its ports in 1854, its basic political and economic structure had long been in need of overhauling. The ruling feudal oligarchy was ineffective and unpopular. Discontent was growing, especially among two important social classes. One was the urban middle class of merchants and artisans. Although the industrial revolution had not yet reached Japan, the country already had populous cities, notably Tokyo (then called Yedo or Edo).

The urban middle class wanted political rights to match their increasing economic power. The other discontented class may be compared roughly with the poorer gentry and lesser nobility of Europe under the Old Regime. These were the samurai, or feudal retainers, a military caste threatened with impoverishment and political eclipse. The samurai dreaded the growth of cities and the subsequent threat to the traditional preponderance of agriculture and landlords. These social pressures, more than outside Western influences, forced the modernization of Japan.

Economically, the transformation proceeded rapidly. By 1914 much of Japan resembled a Western country, for it, too, had railroads, fleets of merchant vessels, a large textile industry, large cities, and big business firms. The industrialization of Japan was the more remarkable in view of its meager supplies of many essential raw materials. But it had many important assets.

Japan’s geographical position with respect to Asia was much like that of the British Isles with respect to Europe. Japan, too, found markets for exports on the continent nearby and used the income to pay for imports. The ambitious Japanese middle class, supplemented by recruits from the samurai, furnished aggressive and efficient business leadership. A great reservoir of cheap labor existed in the peasantry, who needed to find jobs away from the overcrowded farms and who were ready to work long and hard in factories for what seemed very low wages by Western standards.

Politically, Japan appeared to undergo a major revolution in the late nineteenth century and to remodel its government along Western lines. Actually, however, the change was by no means as great as it seemed. A revolution did indeed occur, beginning in 1868 when the old feudal oligarchy crumbled. In 1889 the mikado (emperor) bestowed a constitution on his subjects, with a bicameral Diet composed of a noble House of Peers and an elected House of Representatives.

The architects of these changes were aristocrats and ambitious young samurai, supported by allies from the business world. The result was to substitute a new authoritarian oligarchy for the old. A small group of aristocrats dominated the emperor and the state. The constitution of 1889 provided only the outward appearance of full parliamentary government; the ministry was responsible not to the Diet but to the emperor, and hence to the dominant ruling class. The Diet itself was scarcely representative; the right to vote for members of its lower house was limited to a narrow male electorate, including the middle class but excluding the peasants and industrial workers.

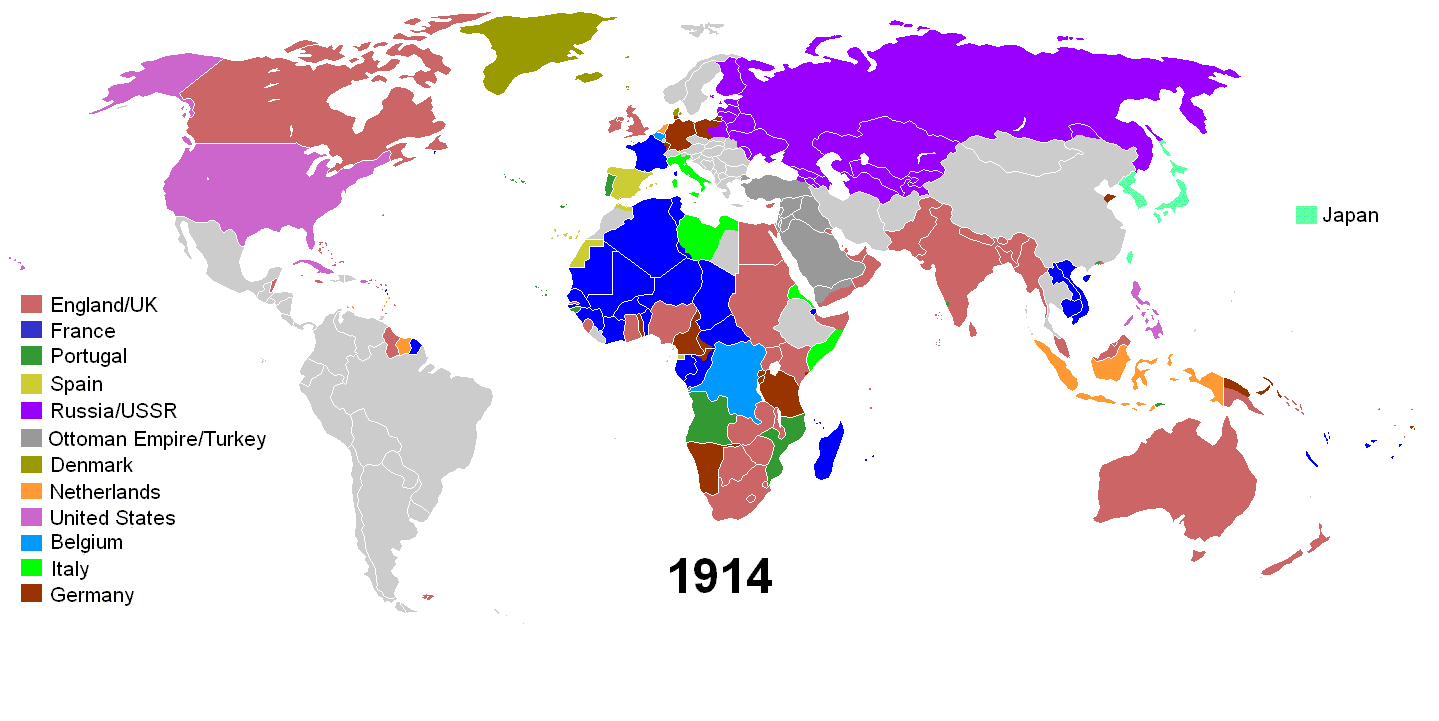

Japan began its overseas expansion by annexing the island of Formosa from China after a short war in 1894-1895. China was also forced to recognize the independence of Korea, which Japan coveted. But Russia, too, had designs on Korea; the result of this rivalry was the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.

Japan secured unchallenged control in Korea (which was annexed in 1910), special concessions in the Chinese province of Manchuria, and the cession by Russia of the southern half of the island of Sakhalin, to the north of the main Japanese islands. Thus Japan had the beginnings of an empire.