Meanwhile, Marx began his friendship and collaboration with Friedrich Engels (1820-1895). In many ways, the two men made a striking contrast.

Marx was poor and quarrelsome, a man of few friends; except for his devotion to his wife and children, he was utterly preoccupied with his economic studies. Engels, on the other hand, was the son of a well-to-do German manufacturer and represented the family textile business in Liverpool and Manchester. He loved sports and high living, but he also hated the evils of industrialism. When he met Marx, he had already written a bitter study, The Condition of the Working Class in England, based on his firsthand knowledge of the situation in Manchester.

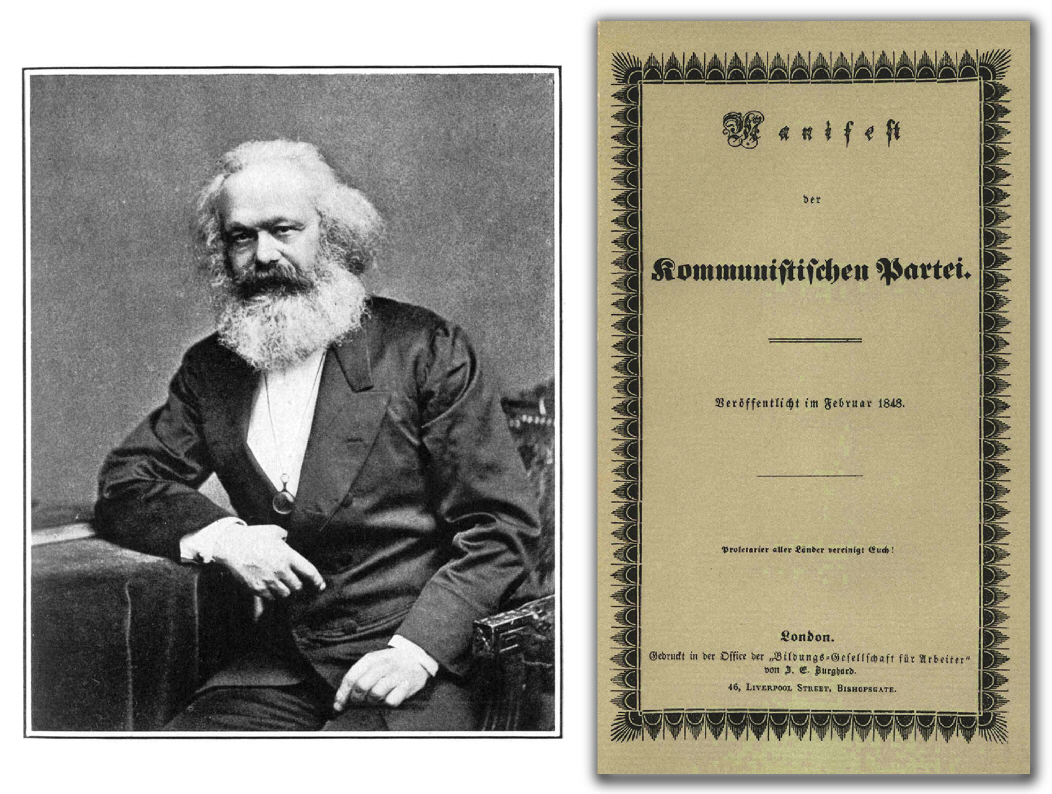

Both Engels and Marx took an interest in the Communist League, a small, secret international organization of radical workers. In 1847 the London office of the Communist League requested them to draw up a program. Engels wrote the first draft, which Marx revised; the result, The Communist Manifesto, remains the classic statement of Marxian socialism.

The Manifesto opened with the dramatic announcement that “A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of Communism.” It closed with a stirring and confident appeal:

Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.

Working men of all countries, unite!”

In between it traced a communist view of history: The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle.” Changing economic conditions determined that the struggle should develop successively between “freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guildmaster and journeyman.”

The guild system gave way first to manufacture by large numbers of small capitalists and then to “the giant, modern industry.” Modern industry would inevitably destroy bourgeois society. It creates mounting economic pressures by producing more goods than it can sell; it creates mounting social pressures by depriving more and more people of their property and forcing them down to the proletariat.

These pressures would increase to the point where a revolutionary explosion would occur. Landed property would be abolished outright; other forms of property would be liquidated more gradually through the imposition of crushing income taxes and the abolition of inherited wealth.

Eventually, social classes and tensions would vanish, and “we shall have an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.” The Manifesto provided only this vague description of the situation that would exist after the revolution. Since Marx defined political authority as “the organized power of one class for oppressing another,” he apparently expected that “the state would wither away” once it had created a classless regime. He also apparently assumed that the great dialectical process of history, having achieved its final synthesis, would then cease to operate in its traditional form.

Marx oversimplified human nature by trying to force it into the rigid mold of economic determinism and ignoring nonmaterial motives and interests. Neither proletarians nor bourgeois have proved to be the simple economic stereotypes Marx supposed them to be: Labor has often assumed a markedly bourgeois outlook and mentality; capital has eliminated the worst injustices of the factory system. No more than Malthus did Marx foresee the notable rise in the general standard of living that began in the mid-nineteenth century and continued well into the twentieth.

Since Marx also failed to take into account the growing strength of nationalism, the Manifesto confidently expected the class struggle to transcend national boundaries. In social and economic warfare, nation would not be pitted against nation; the proletariat everywhere would join to fight the bourgeoisie. In Marx’s own lifetime, however, national differences and antagonisms were, in fact, increasing rapidly from day to day.

The Communist Manifesto anticipated the strengths as well as the weaknesses of the communist movement. First, it foreshadowed the important role to be played by propaganda. Second, it anticipated the emphasis to be placed on the role of the party in forging the proletarian revolution. The communists, Marx declared, were “the most advanced section of the working-class parties of every country.”

In matters of theory, they had the advantage over the great mass of the proletariat of “clearly understanding the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement.” Third, the Manifesto assigned the state a great role in the revolution. Among the policies recommended by Marx were “centralization of credit in the hands of the state” and “extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the state.”

And, finally, the Manifesto clearly established the line dividing communism from the other forms of socialism. Marx’s dogmatism, his philosophy of history, and his belief in the necessity of a “total” revolution made his brand of socialism a doctrine apart.