In summoning the Estates General Louis XVI revived a half-forgotten institution that he thought was unlikely to initiate drastic social and economic reforms. The three estates, despite their immense variation in size, had customarily received equal representation and equal voting power, so that the two privileged orders could be expected to outvote the commoners.

The Estates General of 1789, however, met under unique circumstances. Its election and subsequent meetings took place during an economic crisis marked by a continued influx of unemployed peasants into the cities, especially Paris, and by continued inflation, with prices rising at twice the rate of wages. There was also severe unemployment in some textile centers as a result of the treaty of 1786 with England, which increased British imports of French wines and brandies in return for eliminating French barriers to importing cheaper English textiles and hats.

A final difficulty was the weather. Hail and drought had reduced the wheat harvest in 1788, and the winter of 1788-1789 was so bitter that the Seine froze over at Paris, blocking arrivals of grain and flour by barge, the usual way of shipping bulky goods. Half-starved and half- frozen, Parisians huddled around bonfires provided by the municipal government. By the spring of 1789 the price of bread had almost doubled—a very serious matter, for bread was the mainstay of the diet, and workers normally spent almost half their wages on bread for their families. Now they faced the prospect of having to lay out almost all their wages for bread alone.

France had survived bad weather and poor harvests many times in the past without experiencing revolution; this time, however, the economic hardships were the last straw. Starving peasants begged, borrowed, and stole, poaching on the hunting preserves of the great lords and attacking their game wardens. The concern over meat and bread in Paris erupted in a riot in April 1789 at the establishment of Reveillon, a wealthy wallpaper manufacturer.

The method of electing the deputies aided the champions of reform. In each district of France the third estate made its choice directly, at the public meeting, by choosing electors who later selected a deputy. Since this procedure greatly favored the articulate, middle-class lawyers and government administrators won control of the commoners’ deputation.

The reforming deputies of the third estate found some sympathizers in the second estate and many more in the first, where the discontented poorer priests had a large delegation. Moreover, in a departure from precedent, the king agreed with his advisers’ plan to “double the third,” giving it as many deputies as the other two estates combined to forestall dominance by the aristocracy. Altogether, a majority of the deputies stood prepared to demand drastic changes in the practices of the Old Regime.

In all past meetings of the Estates General, each estate (or order) had deliberated separately, with the consent of two estates and of the Crown required to pass a measure. In 1789 the king and privileged orders favored retaining this “vote by order,” but the third estate demanded “vote by head,” with the deputies from all the orders deliberating together, each deputy having a single vote, at least on tax questions.

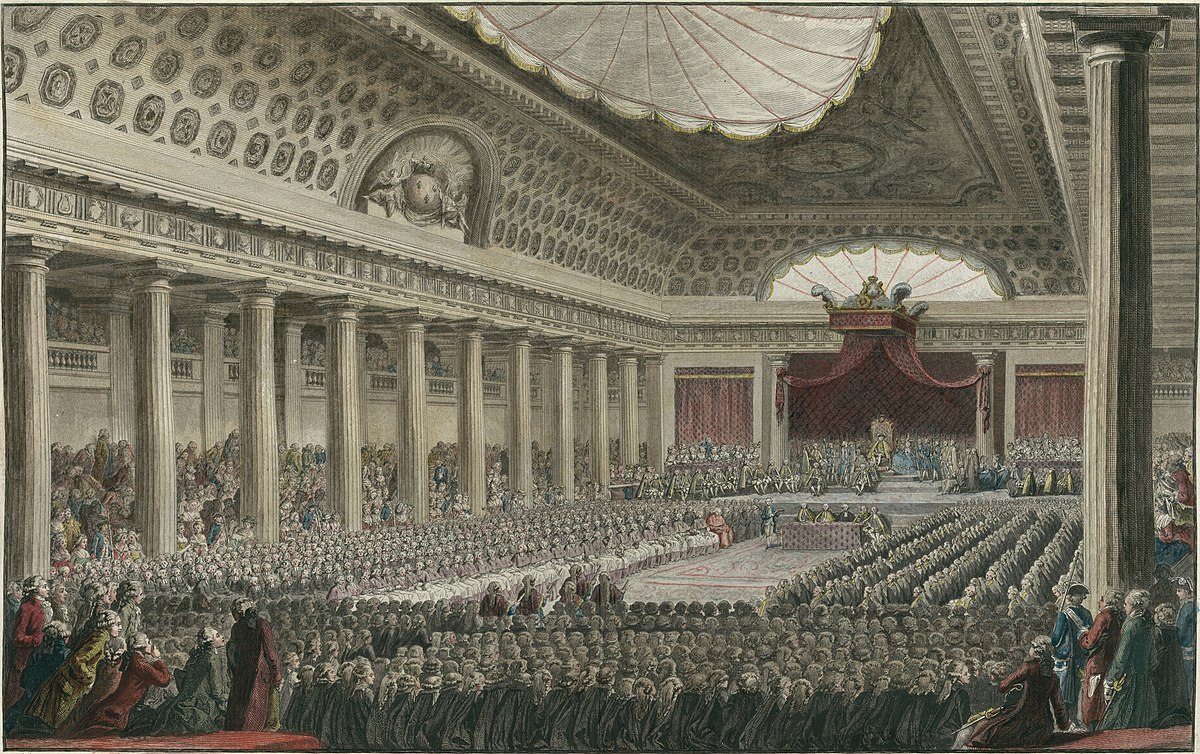

The question of procedure became crucial after the Estates General convened on May 5, 1789, at Versailles. Emmanuel Sieyes, (1748-1836), a priest, and Count Honore Mirabeau (1749-1791), a renegade nobleman, both deputies of the third estate, led the campaign for counting votes by head. On June 17 the assemblage cut through the procedural impasse by accepting Sieyes’s invitation to proclaim itself a National Assembly.

The third estate invited the deputies of the other two estates to join its sessions; a majority of the clerical deputies, mainly parish priests, accepted, but the nobility, leaders of the early phases of the reform movement, refused. When the king barred the commoners from their usual meeting place, the deputies of the third estate and their clerical sympathizers assembled at an indoor tennis court nearby.

There, on June 20, they swore never to disband until they had given France a constitution. Louis replied to the Tennis Court Oath by commanding each estate to resume its separate deliberations. The third estate and some deputies of the first disobeyed. Louis, vacillating as ever, gave in to the reformers, especially when he realized that the royal troops were unreliable.

On June 27 he directed the noble and clerical deputies to join the new National Assembly. The nation, through its representatives, had successfully challenged the king and the vested interests. The Estates General was dead, and in its place sat the National Assembly, pledged to reform French society and give the nation a constitution. The Revolution had begun.