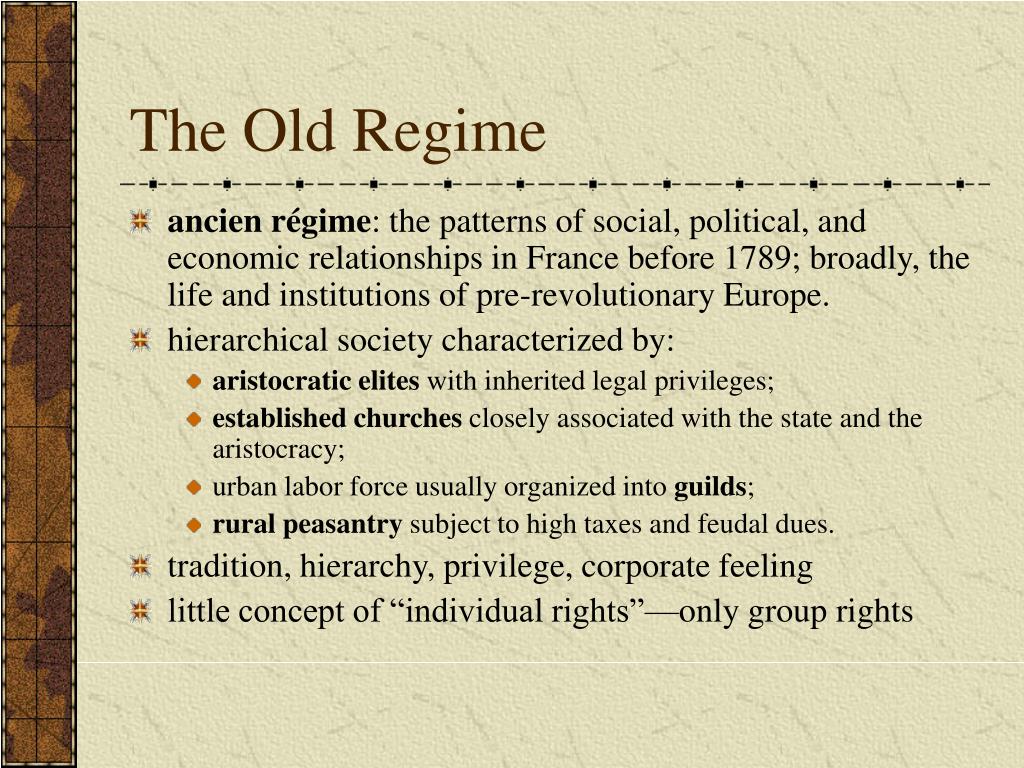

The Old Regime, the institutions that existed in France and Europe before 1789, exhibited features of both the medieval and early modern worlds. The economy was largely agrarian, but in western Europe serfdom had disappeared. The social foundations of the Old Regime were based on three estates. Increasingly, the economic, social, and political order of the Old Regime came under attack in the eighteenth century.

The economic foundations of the Old Regime were challenged in part by the quickening pace of commerce. European states were hard pressed to service debts accumulated in the wars of the seventeenth century. In France, John Law attempted to restore monetary stability by issuing paper money backed by the nation’s wealth. Both in France and England, attempts to manage the national debt caused chaos when these experiments resulted in huge speculative bubbles that burst. The failure of the South Sea Company rocked England, but forced the government to establish a more secure banking system.

Another economic revolution occurred in agriculture. Improvements in farming techniques and the use of new crops such as turnips enabled farmers to produce more food. Increased production ended widespread famines in Europe. In England, enclosures caused widespread social dislocations but created a new labor pool.

A third economic revolution was the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, notably in the textile industry. New machines enabled rapid production and led to the organization of simple factories. New techniques in metallurgy helped make coal mining into a big business.

Britain took the lead in these economic revolutions, becoming the wealthiest nation in the world. Under the first two Hanoverian kings, Parliament was supreme, and the cabinet system took shape under Walpole. Yet Britain was not democratic because only “gentlemen” had the right to vote. For the masses, especially in the growing urban slums of London, life was extremely harsh, but the ruling class was responsive to the need for change.

In the eighteenth century France suffered from mediocre leadership. Cardinal Fleury was the exception. He pursued economic policies designed to stabilize coinage and encourage industry. Despite the failure of Louis XV to institute needed reform, France remained a great power, and French culture dominated Europe.

By the eighteenth century Spain was no longer dominant in the European balance of power. Spanish rulers were preoccupied with Italy, where their claims clashed with those of the Austrian Habsburgs.

Since the mid-seventeenth century, the Hohenzollern rulers of Prussia had worked hard to increase their territories and gain international recognition. Their efforts centered on the economy, absolutism, and the army. The miserly Frederick William I built the Prussian army into the finest force in Europe.

Under Peter the Great, Russia emerged as a great power. Fascinated by Western technology, Peter brought foreign experts to teach Russians modern skills. In foreign policy, Peter expanded Russia by engaging in constant warfare. As a result of the Great Northern War against Sweden (1700-1721), Peter gained his “window on the West.” His economic and social policies fortified the autocracy.

The expansion of Russia and Prussia, rivalry between Britain and France, and competition between Austria and France frequently threatened the balance of power in the eighteenth century. In the early 1700s Britain and France cooperated diplomatically to maintain the balance. By 1740, however, colonial and commercial rivalry set the two powers at odds. Thus, in the War of the Austrian Succession (1739-1748), Britain and Austria were allied against France, Prussia, Spain, and Bavaria.

A diplomatic revolution occurred on the eve of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), when Britain and Prussia paired off against France and Austria, traditional enemies. In the power struggles of the eighteenth century, Britain, Prussia, and Russia were the winners. France, Spain, Austria, and Turkey suffered losses.