Even more spectacular than the rise of Prussia was the emergence of Russia as a major power during the era of Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725). In 1682, at the death of Czar Fedor Romanov, Russia was still a backward country, with few diplomatic links with the West and very little knowledge of the outside world. Contemporaries, Russians as well as foreigners, noted the brutality, drunkenness, illiteracy, and filth prevalent among all classes of society. Even most of the clergy could not read.

Czar Fedor died childless in 1682, leaving a retarded brother, Ivan, and a capable sister, Sophia, both children of Czar Alexis (r. 1645-1676) by his first wife. The ten-year-old Peter was the half-brother of Ivan and Sophia, the son of Alexis by his second wife.

A major court feud developed between the partisans of the family of Alexis’s first wife and those of the family of the second. At first the old Russian representative assembly, the Zemski Sobor, elected Peter czar. But Sophia, as leader of the opposing faction, won the support of the streltsi, or “musketeers,” a special branch of the military.

Undisciplined and angry with their officers, the streltsi were a menace to orderly government. Sophia encouraged the streltsi to attack the Kremlin, and the youthful Peter saw the infuriated troops murder some of his mother’s family. For good measure, they killed many nobles living in Moscow and pillaged the archives where the records of serfdom were kept. Sophia now served as regent for both Ivan and Peter, who were hailed as joint czars. In the end, however, the streltsi deserted Sophia, who was shut up in a convent in 1689; from then until Ivan’s death in 1696 Peter and his half-brother technically ruled together.

The young Peter was almost seven feet tall and extremely energetic. Fascinated by war and military games, he had set up a play regiment as a child, staffed it with full-grown men, enlisted as a common soldier in its ranks (promoting himself from time to time), ordered equipment for it from the Moscow arsenals, and

drilled it with unflagging vigor. When he discovered a derelict boat in a barn, he unraveled the mysteries of rigging and sail with the help of Dutch sailors living in Moscow. Maneuvers, sailing, and relaxing with his cronies kept him from spending time with his wife, whom Peter had married at sixteen and eventually sent to a convent.

He smoked, drank, caroused, and seemed almost without focus; at various times he took up carpentry, shoemaking, cooking, clock making, ivory carving, etching, and dentistry. Peter was a shock to Muscovites, and not in keeping with their idea of a proper czar. Society was further scandalized when Peter took as his mistress a girl who had already been mistress to many others; after she gave birth to two of his children, he finally married her in 1712. This was the empress Catherine (c. 1684-1727), a hearty and affectionate woman who was able to control her difficult husband as no one else could.

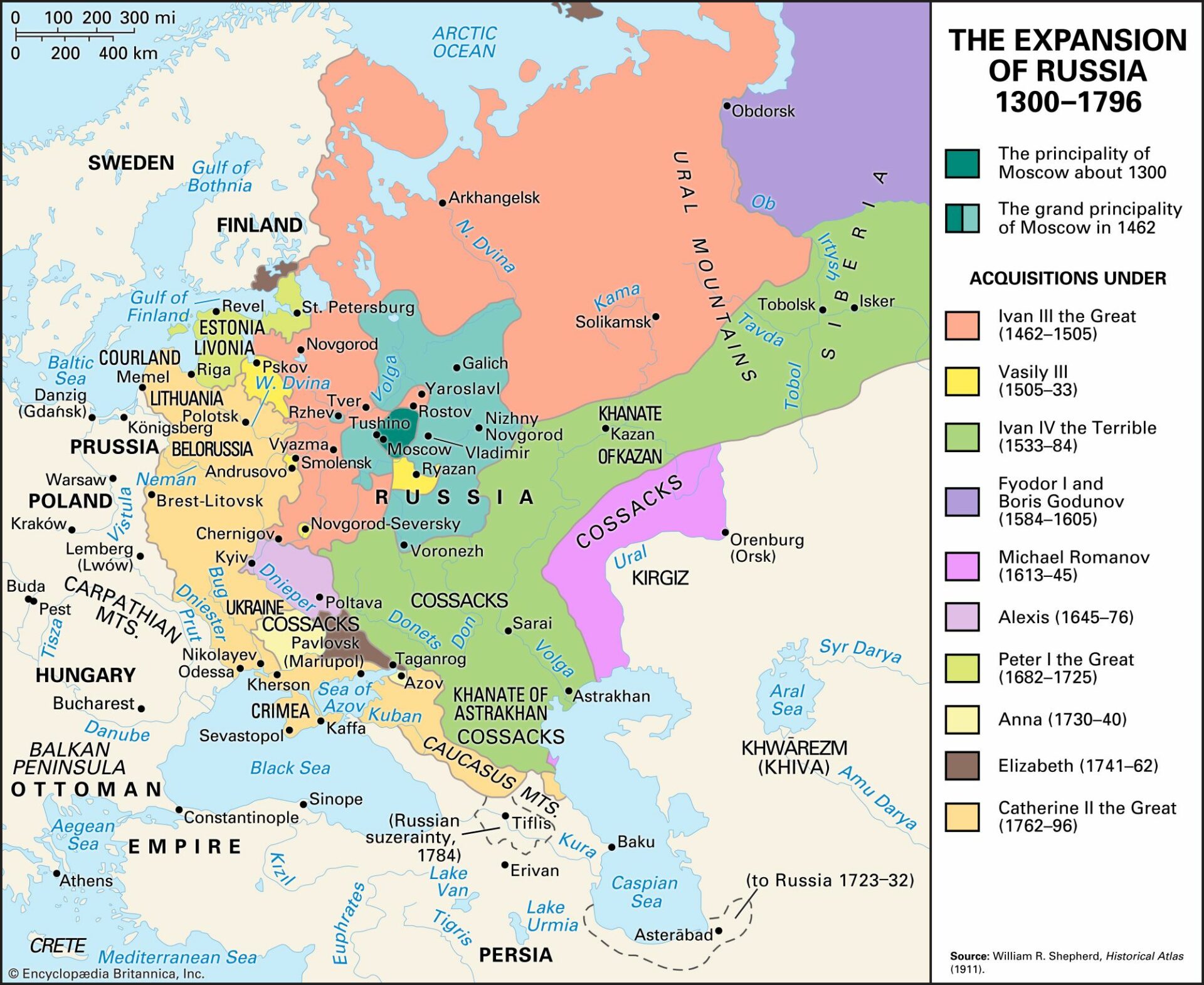

Meanwhile, Peter led a campaign against the Turks around the Black Sea. With the help of Dutch experts, he sailed a fleet of river boats down the Don and defeated the Turks at Azov in 1696. The project of forming an anti-Turkish league with the states of western Europe now gave Peter a pretext for the first trip outside Russia taken by a Russian sovereign since the Kievan period. What fascinated him was Western technology, especially in naval matters, and he planned to go to Holland, England, and Venice. He hired several hundred technicians to work in Russia, raised money by selling the monopoly of tobacco sales in Russia to an English peer, and on his journey visited every sort of factory, museum, or printing press he could find.

Before Peter reached Venice, his trip was interrupted by news that the streltsi had revolted again (1698); Peter rushed home and personally participated in their punishment. Though many innocent men suffered torture and death, Peter broke the streltsi as a power in Russian life. He was more determined than ever to modernize his country, and on the day of his return summoned the court jester to assist him as they went about clipping off courtiers’ beards.

This was an act full of symbolism, for the tradition of the Orthodox church held that God was bearded; if man was made in the image of God, man must also have a beard; and if he was deprived of it, he became a candidate for damnation. Peter now decreed that Russian nobles must shave or else pay a substantial tax for the privilege of wearing their beards. Peter also commanded that all boyars (members of the gentry class) and the city population in general must abandon long robes with flowing sleeves and tall bonnets, and adopt Western-style costume. The manufacture of traditional clothes was made illegal, and Peter took up his shears again and cut off the sleeves of people wearing them.

Peter’s policies at home can be understood only in light of his ever-mounting need to support virtually incessant warfare, together with his intense desire to modernize Russia. His plan for an international crusade against the Turks collapsed when the Austrians and the Ottoman Empire agreed to the Treaty of Karlovitz in 1699. Feeling that Austria had betrayed Russia, Peter made a separate peace with the Turks in 1700. By then he was already planning to attack Sweden. Peter’s allies in the enterprise were Denmark and Poland.

Led by Charles XII (r. 1697-1718), Sweden won the opening campaigns of the Great Northern War (17001721). Charles knocked Denmark out of the fighting, frustrated Poland’s attempt to take the Baltic port of Riga, and completely defeated a larger but ill-prepared Russian force at Narva (1700). Instead of marching into Russia, however, Charles detoured into Poland, where he spent seven years pursuing the king, who finally had to abandon both the Russian alliance and the Polish crown. Charles thereupon secured the election of one of his proteges as king of Poland.

In the interim, Peter rebuilt his armies and took from the Swedes the Baltic provinces nearest to RussiaIngria and Livonia. In the former, he founded in 1703 the city of St. Petersburg, to which he eventually moved the court from Moscow. In 1708 Charles swept far to the south and east into the Ukraine in an effort to join forces with the Cossacks. Exhausted by the severe winter, the Swedish forces were defeated by the Russians in the decisive battle of Poltava (1709). Peter now reinstated his king of Poland, but he was not able to force the Turks to surrender Charles, who had taken refuge with them.

To avenge his defeat Charles engineered a war between Turkey and Russia (1710-1711), during which the Russians made their first appeal to the Balkan Christian subjects of the Turks on the basis of their common faith. Bearing banners modeled on those of Constantine, first emperor of Byzantium, Russian forces crossed into the Ottoman province of Moldavia. Here the Ottoman armies trapped Peter in 1711 and forced him to surrender; the Turks proved unexpectedly lenient, requiring only the surrender of the port of Azov and the creation of an unfortified no man’s land between Russian and Ottoman territory.

On the diplomatic front Russia made a series of alliances with petty German courts. The death of Charles XII in 1718 cleared the way for peace negotiations, though it took a Russian landing in Sweden proper to force a decision. At Nystadt (1721) Russia handed back Finland and agreed to pay a substantial sum for the former Swedish possessions along the eastern shore of the Baltic. The opening of this “window on the West” meant that seaborne traffic no longer had to sail around the northern edge of Europe to reach Russia.

Constant warfare requires constant supplies of men and money. Peter’s government developed a form of conscription according to which a given number of households had to supply a given number of recruits. Although more of these men died of disease, hunger, and cold than at the hands of the enemy, the very length of the Great Northern War meant that survivors served as a tough nucleus for a regular army. Peter also built a Baltic fleet at the first opportunity, but a Russian naval tradition never took hold. From eight hundred ships (mostly very small) in 1725, the fleet declined to fewer than twenty a decade later; there was no merchant marine at all.

To staff the military forces and the administration, Peter rigorously enforced the rule by which all landowners owed service to the state. For those who failed to register he eventually decreed “civil death,” which removed them from the protection of the law and made them subject to attack with impunity. State service became compulsory for life; at the age of fifteen every male child of the service nobility was assigned to his future post in the army, in the civil service, or at court.

When a member of this class died, he was required to leave his estate intact to one of his sons, not necessarily the eldest, so that it would not be divided anew in every generation. Thus the service nobility was brought into complete dependence upon the czar. The system opened the possibility of a splendid career to men with talent, for a person without property or rank who reached a certain level in any branch of the service was automatically ennobled and received lands.

To raise cash, Peter debased the currency, taxed virtually everything—sales, rents, real estate, tanneries, baths, and beehives—and appointed special revenue finders to think of new levies. The government held a monopoly over a variety of products, including salt, oil, coffins, and caviar. However, the basic tax on each household was not producing enough revenue, partly because the number of households had declined as a result of war and misery, and partly because households were combining to evade payment.

Peter’s government therefore substituted a head tax on every male. This innovation required a new census, which produced a most important, and unintended, social result. The census-takers classified as serfs many who were between freedom and serfdom; these people thus found themselves and their children labeled as unfree, to be transferred from owner to owner.

In administration, new ministries (prikazy) were first set up to centralize the handling of funds received from various sources. A system of army districts adopted for reasons of military efficiency led to the creation of provinces. Each province had its own governor, and many of the functions previously carried on inefficiently by the central government were thus decentralized.

Ultimately, Peter copied the Swedish system of central ministries to supersede the old prikazy and created nine “colleges”—for foreign affairs, the army, justice, expenditure, and the like—each administered by an eleven-man collegium. This arrangement discouraged corruption by making any member of a collegium subject to checking by his colleagues; but it caused delays in final decisions, which could only be reached after lengthy deliberations.

To educate future officers and also many civil servants, Peter established naval, military, and artillery academies. Because of the inadequacy of Russian primary education, which was still controlled by the church, foreigners had to be summoned to provide Russia with scholars. At a lower level, Peter continued the practice of importing technicians and artisans to teach their skills to Russians.

The czar offered the inducements of protective tariffs and freedom from taxation to encourage manufacturing. Though sometimes employing many laborers, industrial enterprises remained inefficient. Factory owners could buy and sell serfs if the serfs were bought or sold as a body together with the factory itself. This “possessional” industrial serfdom did not provide much incentive for good work.

Peter also brought the church under the collegiate system. Knowing how the clergy loathed his new regime, he began by failing to appoint a successor when the patriarch of Moscow died in 1700. In 1721 he placed the church under an agency called at first the spiritual college and then the Holy Directing Synod, headed by a layman. Churchmen of the conservative school were more and more convinced that Peter was the Antichrist himself.

The records of Peter’s secret police are full of the complaints his agents heard as they moved about listening for subversive remarks. Peasant husbands and fathers were snatched away to fight on distant battlefields or to labor in the swamps building a city that only Peter appeared to want. The number of serfs increased. Service men found themselves condemned to work for the czar during the whole of their lives and were seldom able to visit their estates.

Among the lower orders of society resistance took the form of peasant uprisings, which were punished with extreme brutality’. The usual allies of the peasant rebels, the Cossacks, suffered mass executions, and sharp curtailment of their traditional independence. The leaders of the noble and clerical opposition focused their hopes on Peter’s son Alexis. Alexis fanned their hopes by indicating that he shared their views. Eventually, he fled abroad and sought asylum with his brother-in-law, the Austrian emperor Charles VI. Promising him forgiveness, Peter lured Alexis back to Russia and had him tortured to death in his presence.

In many respects Peter simply fortified already existing Russian institutions and characteristics. He made a strong autocracy even stronger, a universal service law for service men even more stringent, a serf more of a serf. His trips abroad, his fondness for foreign ways, his regard for advanced technology, his mercantilism, his wars, all had their precedents in Russian history before his reign. Before he attacked it, the church had already been weakened by the schism of the Old Believers.

Perhaps Peter’s true radicalism was in the field of everyday manners and behaviors. His attacks on beards, dress, the calendar (he adopted the Western method of dating from the birth of Christ), his hatred of ceremony and fondness for manual labor—these were indeed new; so, too, were the exceptional vigor and passion with which he acted. They were decisive in winning Peter his reputation as a revolutionary—Peter the Great.

In foreign affairs Russia found itself persistently blocked, even by its allies; whenever Russia tried to move into central or western Europe, Prussia or Austria would desert any alliance with the Russians. As a result, Russian rulers distrusted European diplomacy and followed an essentially defensive policy. The Russians had become a formidable military power capable of doubling their artillery in a single year, with perhaps the best infantry and most able gunnery in Europe by the mid-eighteenth century.

A lack of heavy horses held back the cavalry, as did the undisciplined nature of Cossack warfare. But by the time the Russians occupied East Prussia (from 1758-1761), the Cossacks, too, were noted for their discipline, and European monarchs, fearful of Russian influence, increasingly used propaganda against the czars, even when allied to them.