Baroque composers, especially in Italy, moved further along the paths laid out by their Renaissance predecessors. In Venice, Claudio Monteverdi (1567- 1643) wrote the first important operas. The opera, a characteristically baroque mix of music and drama, proved so popular that Venice soon had sixteen opera houses, which focused on the fame of their chief singers rather than on the overall quality of the supporting cast

and the orchestra.

The star system reached its height at Naples, where conservatories (originally institutions for “conserving” talented orphans) specialized in voice training. Many Neapolitan operas were loose collections of songs designed to show off the talents of the individual stars. The effect of unreality was heightened by the custom of having male roles sung by women and some female roles sung by castrati, male sopranos who had been castrated as young boys to prevent the onset of puberty and the deepening of their voices.

In England, Henry Purcell (c. 1659-1695), the organist of Westminster Abbey, produced a masterpiece for the graduation exercises of a girls’ school, the beautiful and moving Dido and Aeneas. Louis XIV, appreciating the obvious value of opera in enhancing the resplendence of his court, imported from Italy the talented Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687).

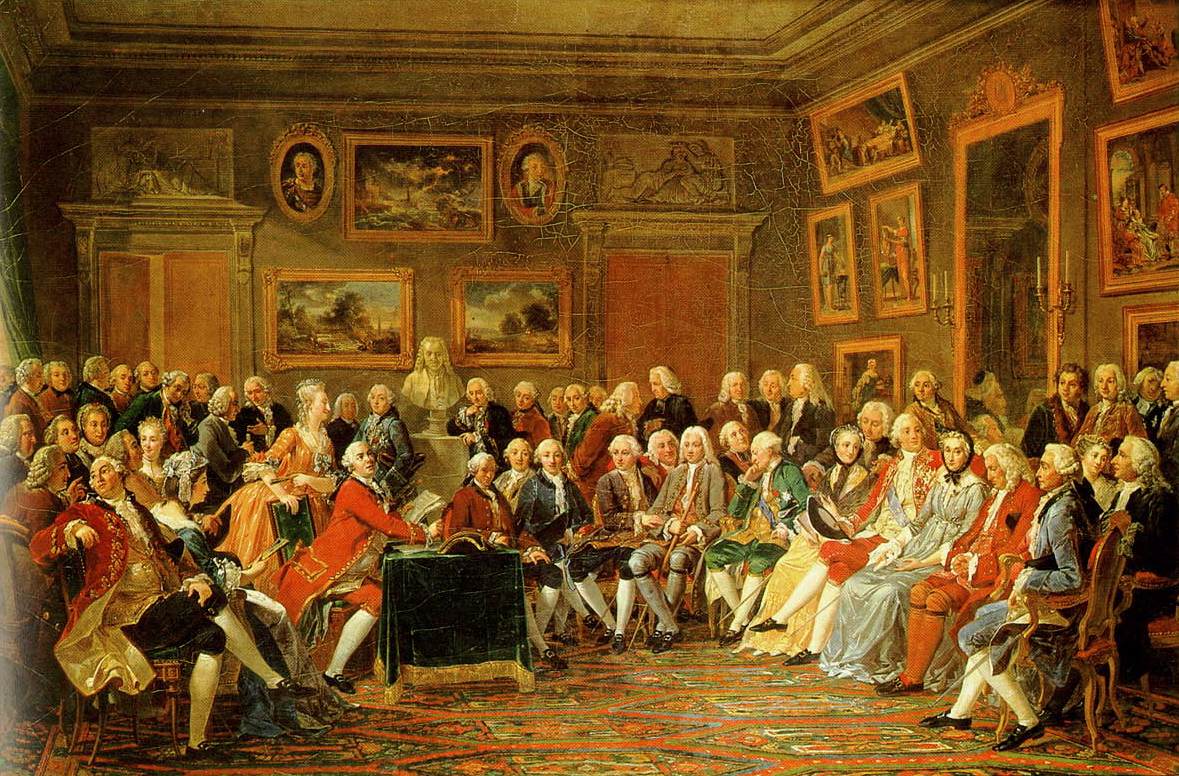

In his operas Lully united French and Italian musical, dance, and literary traditions, and took over the artificiality, gaiety, and weight of court ballet. No artist of the time was more representative, and none was more distant from the concerns of the people who, though they might admire the majesty of the court from a distance, could know no part in it—the common people, who saw little if any of the art and architecture, read none of the literature, and heard none of the music of baroque high society.