The Republic of Florence, like that of Milan, was a fragile combination of aristocratic and democratic elements. It was badly shaken by Guelf-Ghibelline rivalries and by the emergence of an ambitious wealthy class of bankers and merchants. In the twelfth century the commune had acquired a dominant position.

Florence exemplified the growth of social mobility, new wealth, extensive trade, and complex credit operations. Increasingly society was based on the need to work cooperatively, as best shown by the widespread use of credit in both public and private finance. There grew a productive tension between the cult of poverty (and insecurity) that was deeply rooted in monastic and philosophical Christian thought and the desire for wealth (and security) that lay at the base of the growth of the Italian cities. The factionalism, therefore, was not simply petty, for it expressed very major concerns in a changing society.

In the late 1200s Guelf capitalists prevailed over the Ghibelline aristocrats and revised the constitution of the republic so that a virtual monopoly of key government offices rested with the seven major guilds, which were controlled by the great woolen masters, bankers, and exporters. They denied any effective political voice to the artisans and shopkeepers of the fourteen lesser guilds, as well as to Ghibellines, many nobles, and common labor ers. But feuds within Guelf ranks soon caused a new exodus of political exiles, including the poet Dante.

Throughout the fourteenth century and into the fifteenth, political factionalism and social and economic tensions tormented Florence, though they did not prevent a remarkable cultural growth. The politically unprivileged sought to make the republic more democratic; they failed in the long run because of the oligarchy’s resilience and also because the reformers themselves were torn by the hostility between the lesser guilds and the ciompi or poor day laborers. The English king Edward III’s repudiation of his debts to the Florentine bankers, followed in the 1340s by disastrous bank failures, weakened the major guilds enough to permit the fourteen lesser guilds to gain supremacy.

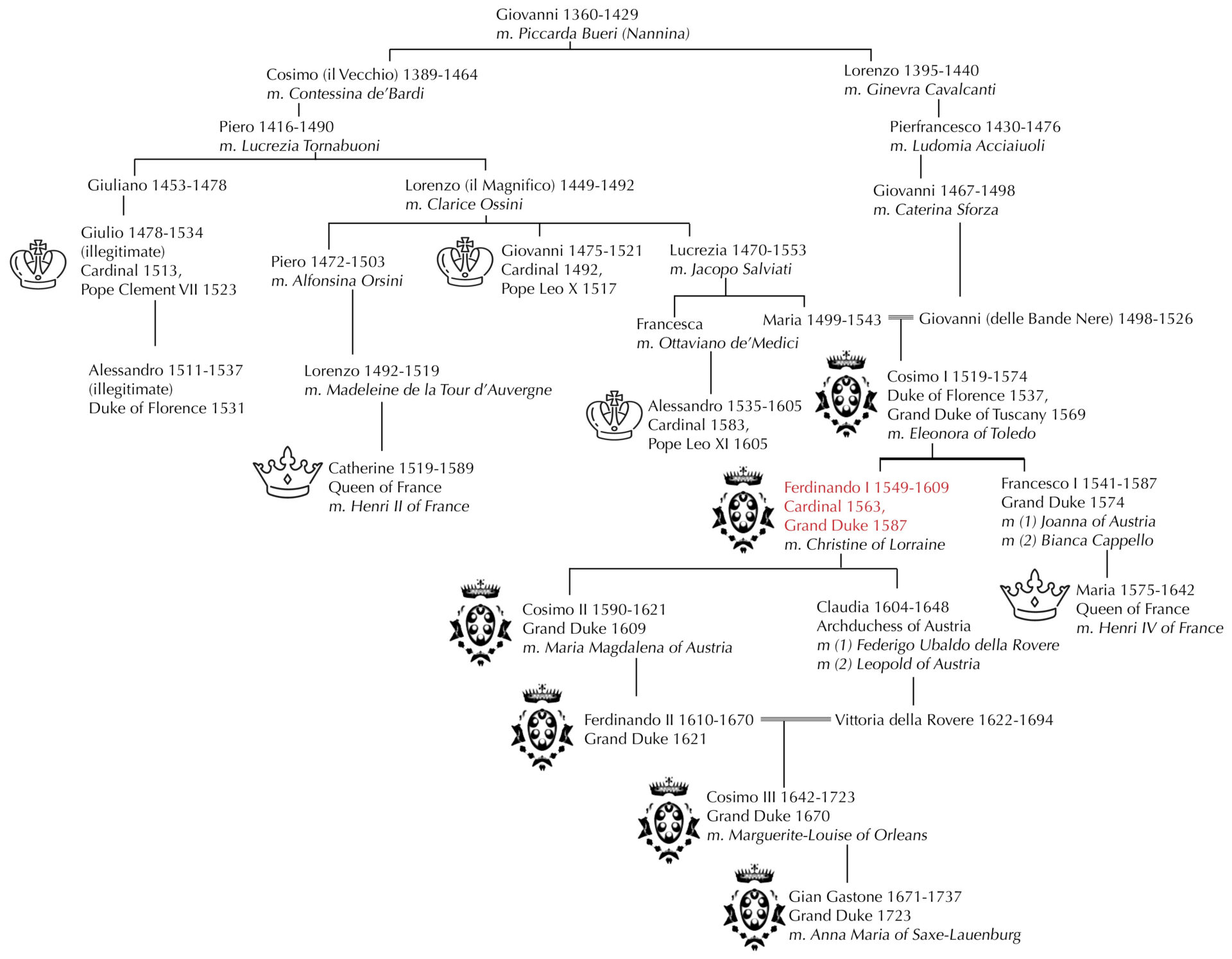

Unrest persisted, however, reaching a climax with the revolution of the ciompi in 1378. Wool carders, weavers, and dyers gained the right to form their own guilds and to have a minor voice in politics. Continued turbulence permitted the wealthy to gain the upper hand over both the ciompi and the lesser guilds. The prestige of the reestablished oligarchy rose when it defended the city against the threat of annexation by the aggressive Visconti of Milan. Finally, in the early 1400s, a new rash of bankruptcies and a series of military reverses weakened the hold of the oligarchy. In 1434 some of its leaders were forced into exile, and power passed to a political champion of the poor, Cosimo de’ Medici.

For the next sixty years (1434-1494) Florence was run by the Medici, who were perhaps the wealthiest family in all Italy. Their application of the graduated income tax bore heavily on the rich, particularly on their political enemies, while the resources of the Medici bank were employed to weaken their opponents and assist their friends. They operated quietly behind the facade of republican institutions. Cosimo, for example, seldom held any public office and kept himself in the background.

The grandson of Cosimo was Lorenzo, ruler of Florence from 1469 to 1492 and known as the Magnificent. Though possessing the wide-ranging interests admired by his contemporaries, Lorenzo was not without flaws. His neglect of military matters and his financial carelessness, which contributed to the failure of the Medici bank, left Florence poorly prepared for the wars that were to engulf Italy in the late 1400s.