A final development of these two centuries was to prove of the utmost importance for the future Russia. This was the slow and gradual penetration of foreigners and foreign ideas, a process welcomed with mixed feelings by those who prized the technical and mechanical learning they could derive from the West while fearing Western influence on society and manners. This ambivalent attitude toward Westerners and Western ideas became characteristic of later Russians.

The first foreigners to come were the Italians, who helped build the Kremlin at the end of the fifteenth century. But they were not encouraged to teach the Russians their knowledge, and they failed to influence even the court of Ivan III in any significant way. The English, who arrived in the mid-sixteenth century as traders to the White Sea, were welcomed by Ivan the Terrible.

He gave the English valuable privileges and encouraged them to trade their woolen cloth for Russian timber and rope, pitch, and other naval supplies. The English were the first foreigners to teach Russians Western industrial techniques. Toward the middle of the seventeenth century the Dutch were able to displace the English as the most important foreign group engaged in commerce and manufacturing, opening their own glass, paper, and textile plants in Russia.

After the accession of Michael Romanov in 1613, the foreign quarter of Moscow, always called “the German suburb,” grew rapidly. Foreign technicians received enormous salaries from the state. Foreign merchants sold their goods; foreign physicians and druggists became fashionable. By the end of the seventeenth century Western influence was fully apparent in the life of the court. A few nobles began to buy books and form libraries, to learn Latin, French, and German. The people, meanwhile, distrusted and hated the foreigners, looted their houses when they dared, and jeered at them in the streets.

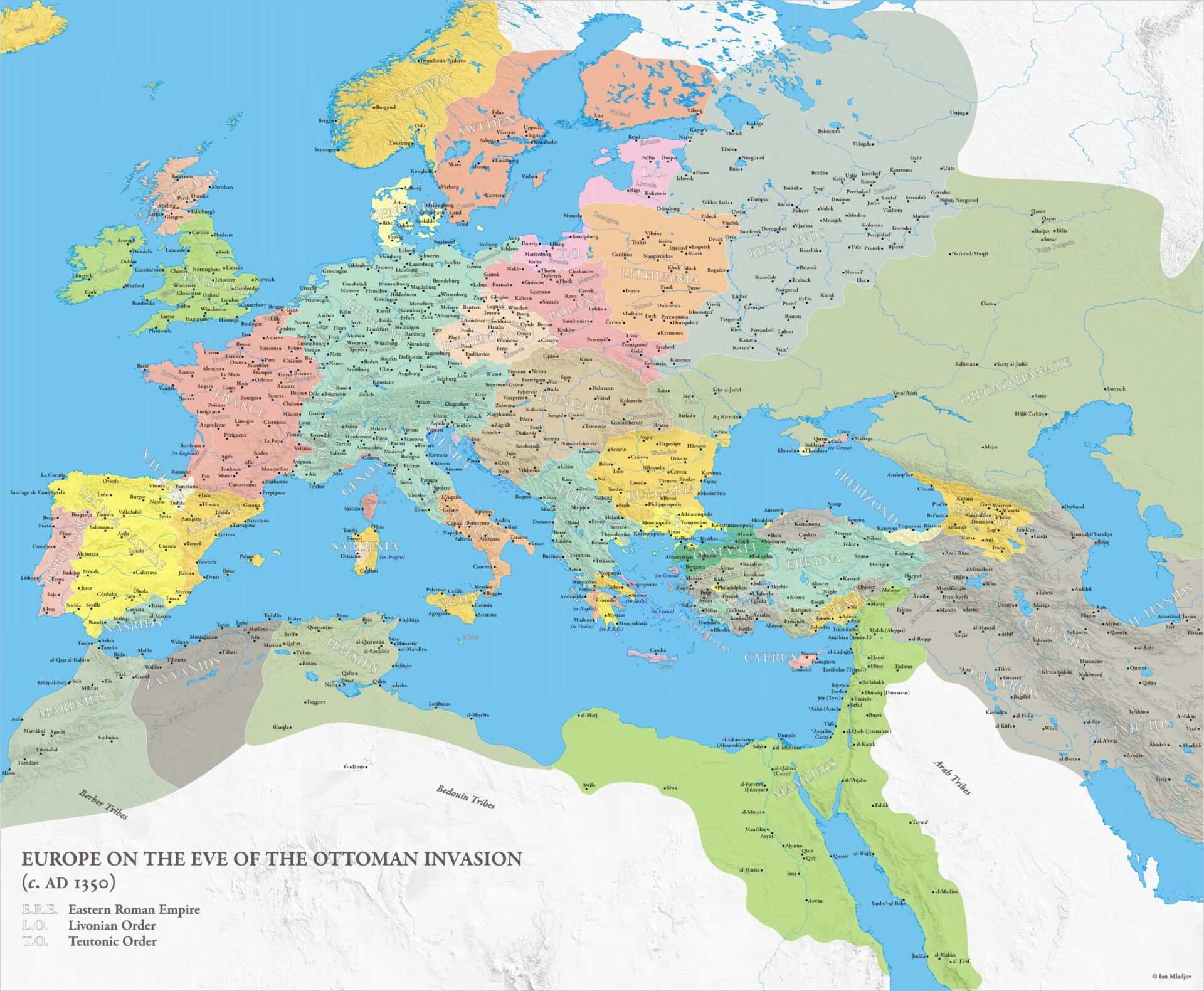

Suspicion of foreign influences had divided the Russian church, cut the people off from sources of change, smothered the development of even modest representative institutions, assured the continuation of serfdom, and, together with the impact of the Ottoman Empire, kept the East under medieval conditions to the end of the seventeenth century. The Middle Ages came to have quite different dates in East and West, reflecting the different pace of development.