The advance from the Old Stone Age (Paleolithic) to the New (Neolithic) was marked by certain major changes, found first in the Near East. One of these was the domestication of animals for food. Humans had tamed dogs and used them in the hunt long before. But when they kept goats, pigs, sheep, and the ancestors of our cows in pens, they could eat them when their meat was young and tender. without having to hunt them down when they were fully grown. Parallel with this went the first domestication of plants for food—a kind of wheat and barley. Finally, temporary shelter was replaced by houses with some permanence. Accompanying these fundamental steps was the practice of a new technology, the baking of clay vessels, which were much easier to make than stone ones. It is chiefly by studying the surviving varieties of such vessels and the types of glazes and decorations the potters used, that modern

scholars have been able to date the sites where ancient people lived before writing was developed.

At Jericho, in the Jordan Valley, archaeologists have excavated a town radiocarbon-dated at about 7800 B.C. that had extended over about eight acres and included perhaps three thousand inhabitants. These people lived in round houses with conical roofs and had a large, columned building in which were found many figurines of animals and statues of a man, a woman, and a male child. It was almost surely a temple of some kind. All this dates from a time when people did not yet know how to make pots. Evidence suggests that the site was occupied far earlier and then abandoned for reasons not yet understood, then occupied once again in the eleventh century B.C

In Catal Huyuk in southern Turkey, discovered in 1961 and dating to 6500 B.C., the people grew their own grain, kept sheep, and wove the wool into textiles. They also had a wide variety of pottery. A sculpture of a female giving birth to a child, a bull’s head, boars’ heads with women’s breasts running in rows along the lower jaws, and many small statuettes were all found together. A bull and a double ax painted on a wall seem to look forward to the main features of a religion of ancient Crete.

Far to the east, in modern Iraq (ancient Mesopotamia, “between the rivers” Tigris and Euphrates), lay Jarmo, dated about 4500 B.C., another Neolithic settlement. A thousand years later than Jarmo, about 3550 B.C., and far to the south, at Uruk on the banks of the Euphrates River, farmers were using the plow to scratch the soil before sowing their seeds and were already keeping the business accounts of their temple in simple picture writing. This was the great leap forward that took human beings out of prehistory and into history. Similar advances are also found in Egypt at roughly the same time.

During the 1960s, still farther to the east in various parts of modern Iran, archaeologists found several early Neolithic sites, some of which seem to go back in time as far as Jericho or even before. Many of these Iranian discoveries are still unpublished, and much work remains to be done. But from 6000 B.C. there are several sites in northwest Iran rather like Jarmo, giving plenty of evidence of domesticated animals and grains. And even earlier, perhaps around 7000, in southwest Iran very near the Mesopotamian eastern border, there are mud-brick houses and the same clear evidence of goat and sheep raising and cereal cultivation.

In south-central Iran a fresh site was discovered in 1967 at Tepe Yahya, where the earliest settlement in a large earth mound proved to be a Neolithic village of about 4500 B.C. Here, along with the animal bones and cereal remains, archaeologists found in a mud-brick storage area not only pottery and small sharpened flints set in a bone handle to make a sickle but also an extraordinary figurine sculptured of dark green stone, which in both material and subject is more complex than anything found previously.

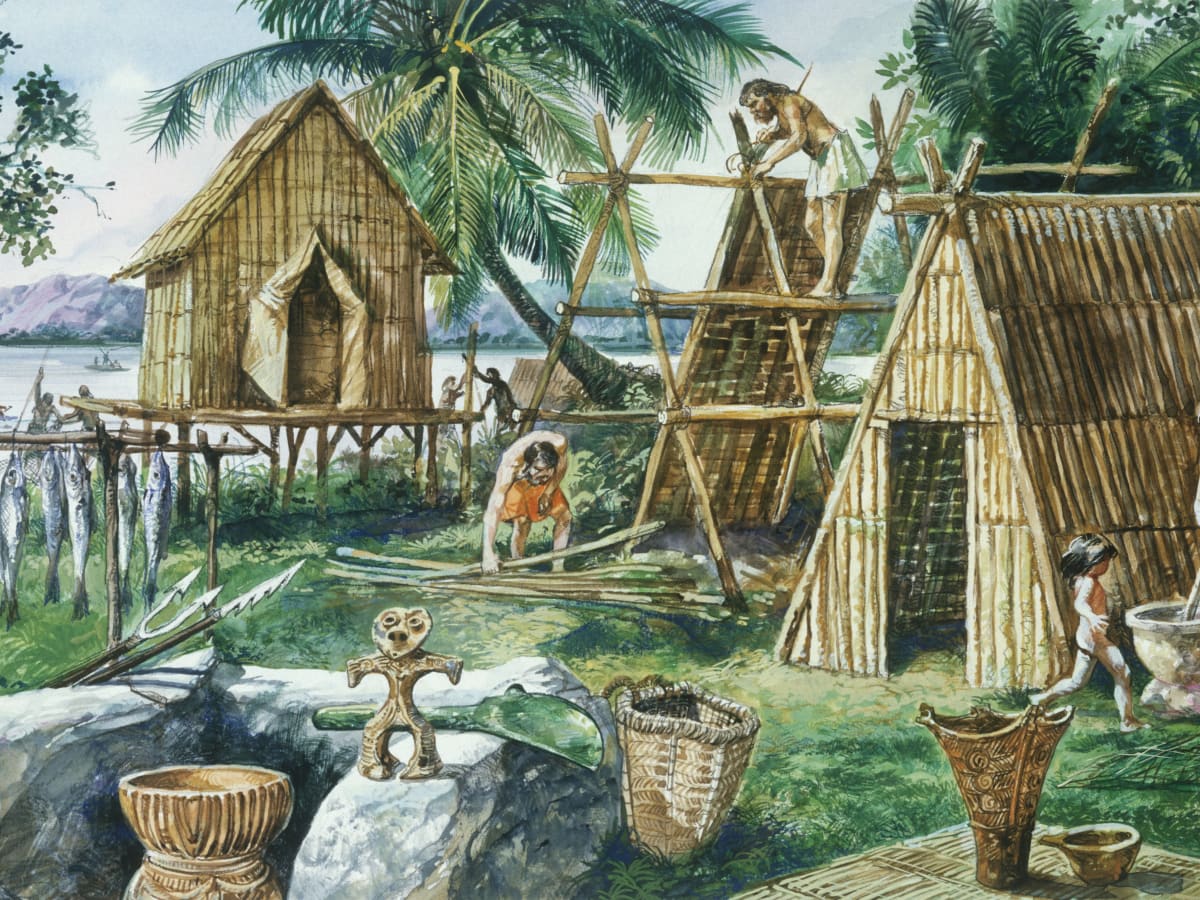

Neolithic remains also have been found in many places around the Mediterranean and far to the north, but the climate in those places was far less favorable. Even when Neolithic people managed to triumph over the environment—as in lake settlements in Switzerland, where they built frame houses on piles over the water— the triumph came later (in this case about 2500 B.C.). It was the inhabitants of the more favored regions who got to the great discoveries first. It was they who learned copper smelting and the other arts of metallurgy and first lived in cities.

Writing, metallurgy, and urban life are among the early marks of civilization. Soon after these phenomena appeared in the Tigris-Euphrates valleys, along the Nile, and in Iran, they appeared also in the valley of the Indus, along Chinese rivers, in Southeast Asia, and in South and Central America. In North America, too, recent discoveries have carried knowledge back twenty thousand wears and more.