In the seventeenth century Archbishop James Ussher (1581-1656) of the Church of England carefully worked out from data given in the Bible what he believed to be the precise date of the creation of the world by God. It was, he said, 4004 B.C. Adding the sixteen hundred or so years since the birth of Christ, he concluded that the earth was then under six thousand years old. We smile at the generations that accepted Ussher’s views because we now believe that the earth is billions of years old and that organic life may go back several billion years.

Beginning in 1951, a series of archaeological digs in east-central Africa in and around Olduvai Gorge turned up fragments of a small creature that lived between 19 million and 14 million years ago, called Kenyapithecus (Kenya ape), who seems to have made crude tools. Kenya ape may not be a direct human ancestor but may have branched off from a primate 10 million years older still. By about 2 million years ago a creature more like our ideas of humankind had made its appearance: Homo habilis (the skillful one). A mere quarter of a million years later came Zinjanthropus, who was perhaps related to a humanlike animal about the size of a chimpanzee called Australopithecus, a term meaning “southern ape.” Australopithecus may have been a vegetarian (to judge by its teeth) and seems to have ceased evolving while Homo habilis, who ate meat, continued to evolve in the direction of the biologically modern human, Homo sapiens (the one who knows). All these humanlike animals had larger skulls than the apes had. In another three quarters of a million years (approximately a million years ago), Homo habilis began to look like a being long known as Java man, who lived about 700,000 B.C. First found in Java in the late 1880s, Pithecanthropus erectus (ape-man that walks erect) is now termed Homo erectus. A somewhat later stage is represented by Peking man of about 500,000 B.C.

Homo sapiens, who appeared first in Europe only about thirty-seven thousand years ago, came upon a land of forests and plains that had already been occupied for perhaps a hundred thousand years by another Homo erectus, Neanderthal man. Neanderthal man was apparently capable of thought as we understand the term. We cannot yet locate Neanderthals accurately on a hypothetical family tree, but they probably represent another offshoot from the main trunk.

Neanderthal culture was based on hunting and food gathering. They possessed stone tools and weapons, apparently cooked their meat, wore skins, and commemorated their dead through ritual burials. However, what we know remains sophisticated guesswork.

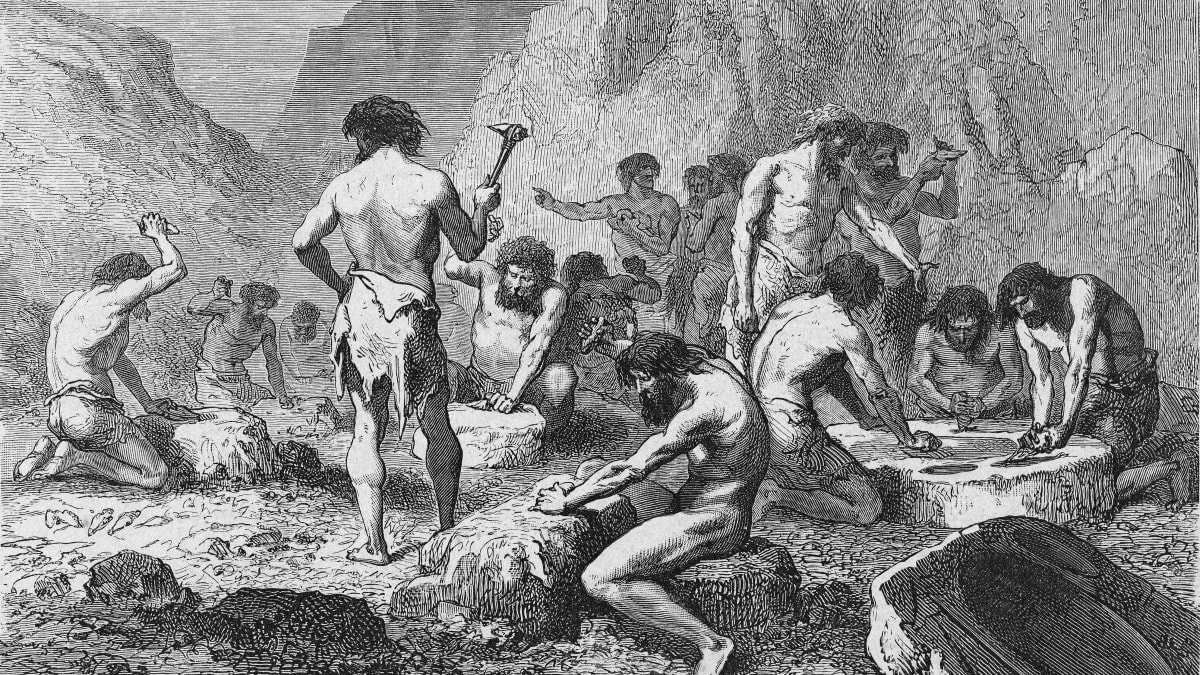

We know so little about what was happening during those hundreds of thousands of years that for the historian almost all of this time belongs to prehistory—that is, history before humanity left written records. During those centuries the advance of the human animal was enormously slow. The first real tools were stones that were used to chip other stones into useful instruments. And it was by those stone weapons and tools that early humans lived for hundreds of thousands of years.

Archaeologists have named the early periods of human culture from the materials used. During the Old Stone (Paleolithic) Age, roughly before 8000 B.C., people used chipped stone tools. About 8000 B.C.—perhaps much, much earlier in some places and much later in others—the development of farming and the use of more sophisticated stone implements marked the beginning of the New Stone (Neolithic) Age. About 3000 B.C. the invention of bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) led to the Bronze Age and new forms of human life and society. Still later, further experiments with metals ushered in the Iron Age.

Paleolithic people left remains scattered widely in Europe and Asia and took refuge in Africa from the glaciers that periodically moved south over the northern continents and made life impossible there. Wherever they went, they hunted to eat, and fought and killed their enemies. They learned how to cook their food, how to take shelter from the cold in caves, and eventually how to specialize their tools. They made bone needles with which to sew animal hides into clothes with animal sinews; they made hatchets, spears, arrowheads, and awls.

They also created art. At Lascaux in France, at Altamira in northern Spain, and on the Coa. River in Portugal, Paleolithic artists left remarkable paintings in limestone caves, using brilliant colors to depict deer, bison, and horses. The Lascaux cave paintings, found in 1940, were closed to the public in 1960 to protect them against the thousands of tourists they attracted.

We can only guess why the Paleolithic artist painted the pictures. Did the artist think that putting animals on the walls would lead to better hunting? Would their pictures give the hunters power over them, and so ensure the supply of food? Were the different animals also totems of different families or clans? Sometimes on the walls of the caves we find paintings of human hands, often with a finger or fingers missing. Were these hands simple testimony of appreciation of one of humanity’s most extraordinary physical gifts: the hand, with its opposable thumb (not found in apes), which made tool making possible? Were they efforts to ward off evil spirits by holding up the palm or making a ritual gesture? We do not know.

Besides the cave paintings and Venuses (small female statuettes) and tools, made with such variety and with increasing skill from about 35,000 B.C. to about 8000 B.C., archaeology has yielded a rich variety of other finds, especially concerning the development of the calendar. Bone tools found in Africa and Europe show markings whose sequence and intervals may record lunar periods. Sometimes only one or two lunar months had been observed, sometimes six, sometimes an entire year. Eventually, the Paleolithic craftsman learned to make the notations more complex, sometimes engraving them in a crosshatched pattern, sometimes adding extra angled marks at important dates.

Once we realize that late Old Stone Age peoples may have been keeping a calendar to enable them to predict seasonal changes from year to year, and therefore were presumably regulating their hunting and other activities, we get a new perspective on the quality of their minds. The new perspective is so vivid that the “mystery” of their extraordinary skills becomes far less mysterious. Where we find on the same piece of Paleolithic ivory a budding flower, sprouting plants, grass, snakes, a salmon, and a seal—which appeared in spring in the local rivers— we may have an object that symbolically represents the earth’s reawakening after winter. When such symbols of spring appear with the lunar calendric notation, we are looking at something very like an illustrated calendar.

In the same way, the stone venuses may mark the procession of the seasons, of fertility, conception, and birth. Some representations can be interpreted as sacrifices. Certain animals—reindeer, bison, horses—appear on the artifacts associated with females; others—bears and lions— with males. Late Old Stone Age people apparently had a mythology that involved tales of the hunt; a ritual that involved killing and sacrifice; and a deep awareness of the passing of time. A nude figure of a woman holding a bison horn that looks like a crescent moon and is marked with thirteen lines (the number of lunar months in a year) may be humanity’s first recognizable goddess. She may be the forerunner of the bare-breasted Neolithic moon goddess long known as the Mistress of the Animals, who appears with crescent, fish, flower, plant, bird, tree, and snake, and with a consort who plays sun to her moon and hunts the animals of nature and of myth. Though the people of the Old Stone Age remain dim and remote to us, such research for the first time make them more recognizably human.