-

Economics | Napoleon and France

Political aims also governed the economic program of an emperor determined to promote national unity. French peasants wanted to be left alone to enjoy the new freedom acquired in 1789. Napoleon did little to disrupt them, except to raise army recruits.

-

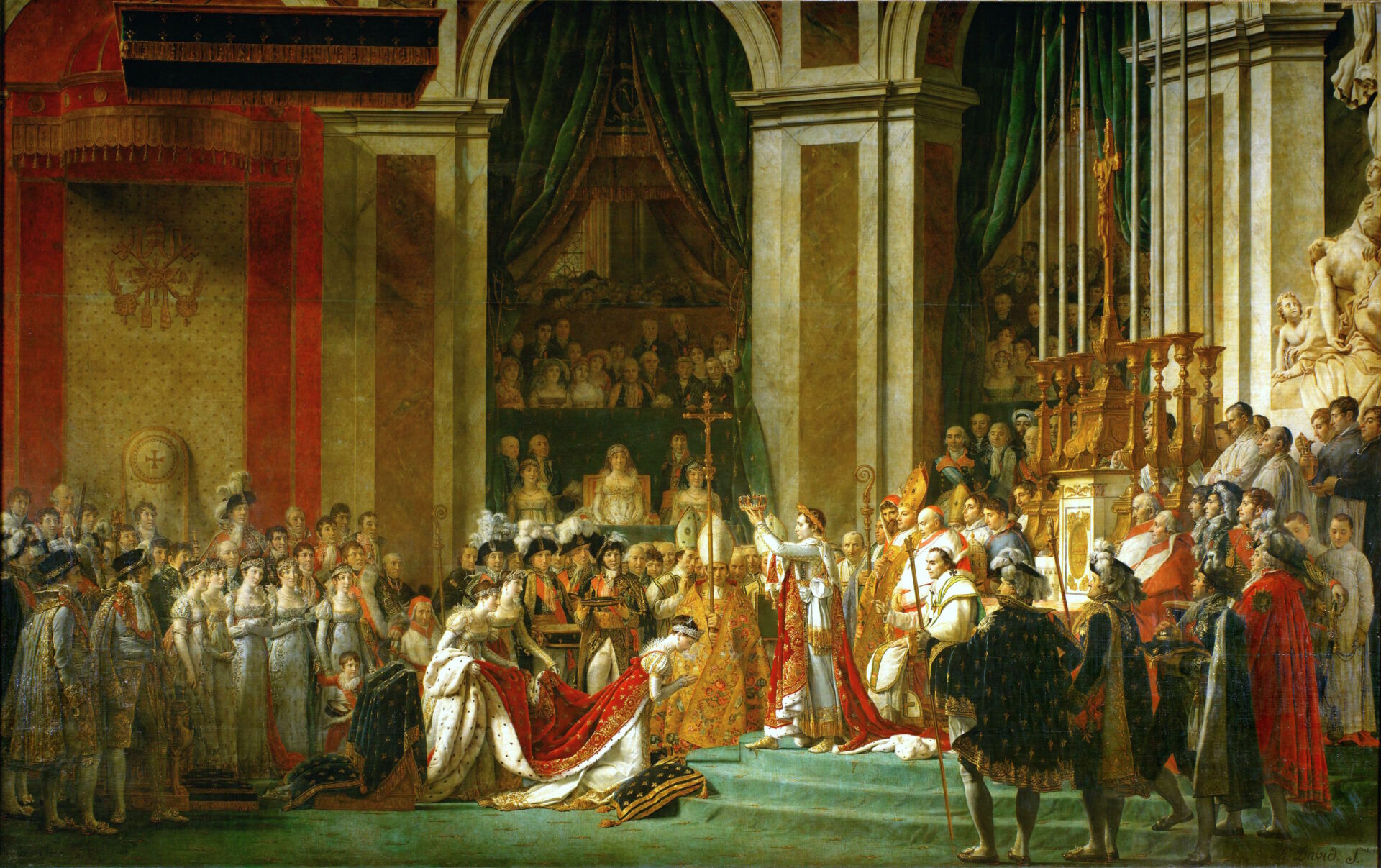

Religion and Education | Napoleon and France

Political considerations generally colored Napoleon’s decisions on religion. Since French Catholics loathed the anti-clericalism of the Revolution, Napoleon sought to appease them by working out a reconciliation with Rome. The Concordat (a treaty with the Vatican) negotiated with Pope Pius VII (r. 1800-1823) in 1802 accomplished this reconciliation. While it canceled only the most obnoxious…

-

Law and Justice | Napoleon and France

Napoleon revived some of the glamor of the Old Regime but not its glaring inequalities. His series of law codes, the Code Napoleon (1804-1810), declared all men equal before the law without regard to rank and wealth. It extended to all the right to follow the occupation and embrace the religion of their own choosing.…

-

Consulate and Empire | Napoleon and France

The constitution of the Year VIII was the fourth attempt by revolutionary France to provide a written instrument of government, its predecessors being the constitutions of 1791, 1793, and 1795. The new document erected a very strong executive, the Consulate. Although three consuls shared the executive, Napoleon as first consul left the other two only…

-

Bonaparte’s Rise | Napoleon and France

By the close of 1795 only Britain and Austria remained officially at war with France. To lead the attack against Habsburg forces in northern Italy, the French Directory picked a youthful general who was something of a philosophe and revolutionary, as well as a ruthless, ambitious adventurer. He was born Napoleone Buonaparte on Corsica in…

-

Napoleon and France

As late as 1792 Catherine the Great predicted that ten thousand soldiers would suffice to douse the “abominable bonfire” in France. The war that broke out in the spring of 1792 soon destroyed such illusions. Almost all the European powers eventually participated, and the fighting ranged far beyond Europe. By the time the war was…

-

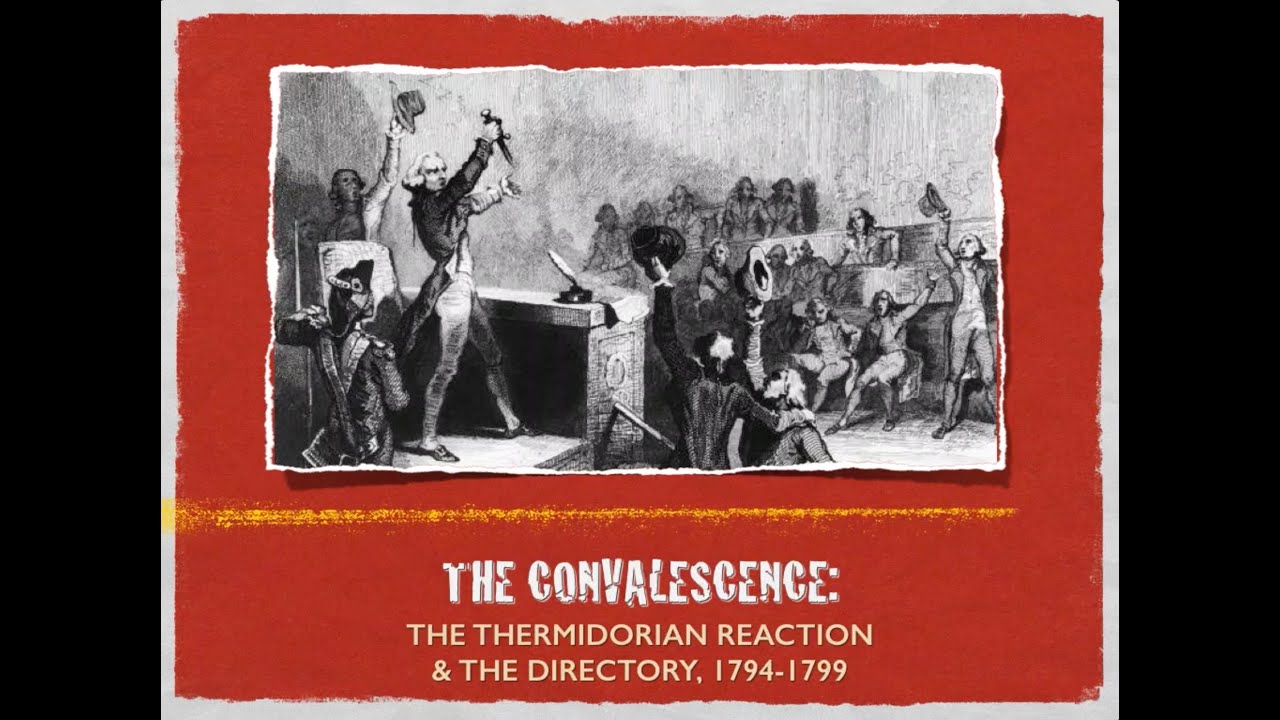

The Thermidorean Reaction and the Directory, 1794-1799 | The French Revolution

The leaders of the Thermidorean Reaction, or the move toward moderation, many of them former Jacobins, now dismantled the machinery of the Terror.

-

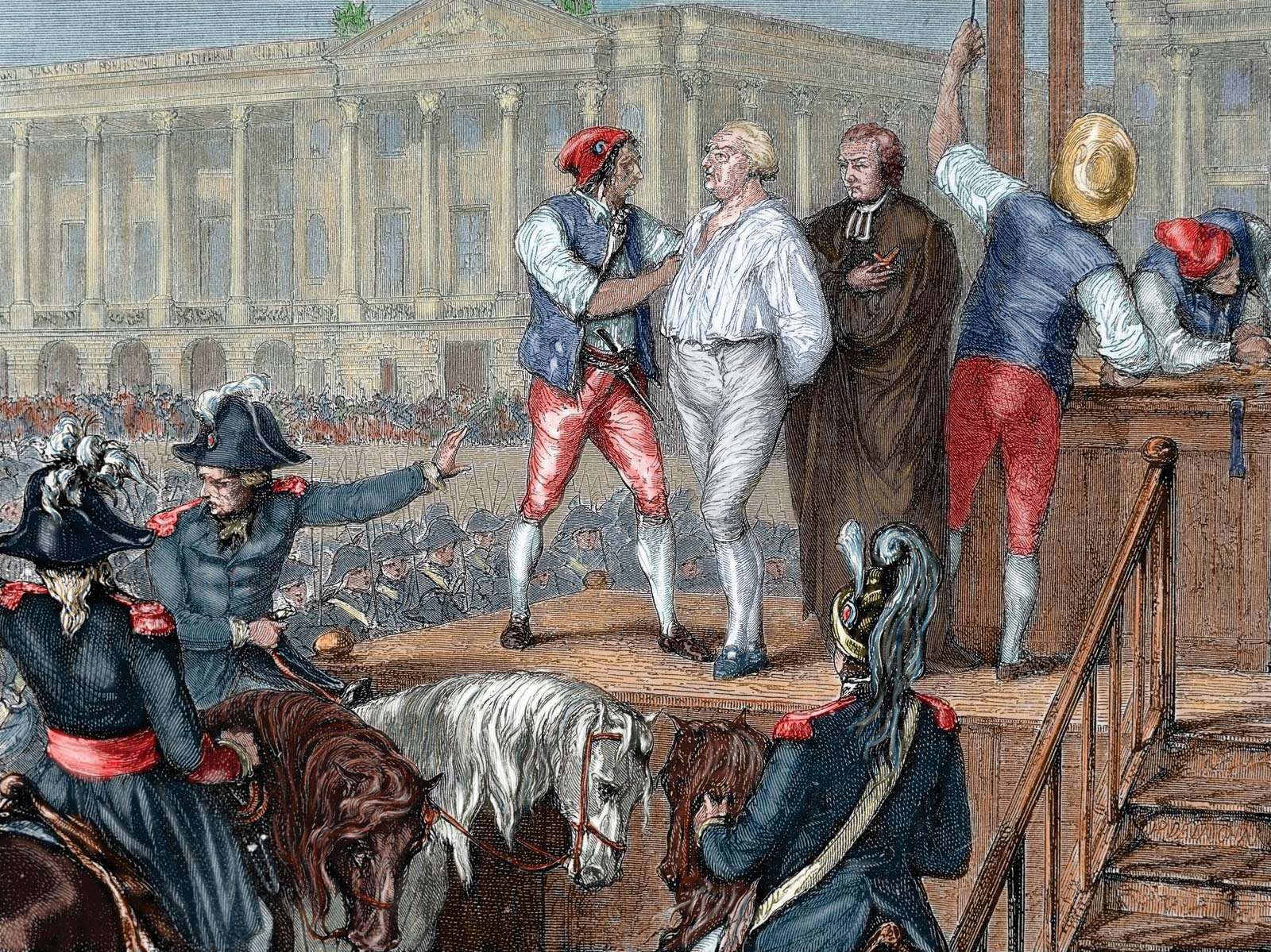

The Death of a King

There were many eyewitnesses to the events of the French Revolution. The English, of course, followed its destructive path with fascination. The following is an account (no doubt biased) by one such eyewitness, Henry Essex Edgeworth, a Catholic who went to Paris to be spiritual director to the Irish who lived in the capital. The…

-

The Reign of Terror, 1793-1794 | The French Revolution

How was it that the advocates of democracy now imposed a dictatorship on France? Let Robespierre explain: To establish and consolidate democracy, to achieve the peaceful rule of constitutional laws, we must first finish the war of liberty against tyranny . . . We must annihilate the enemies of the republic at home and abroad,…

-

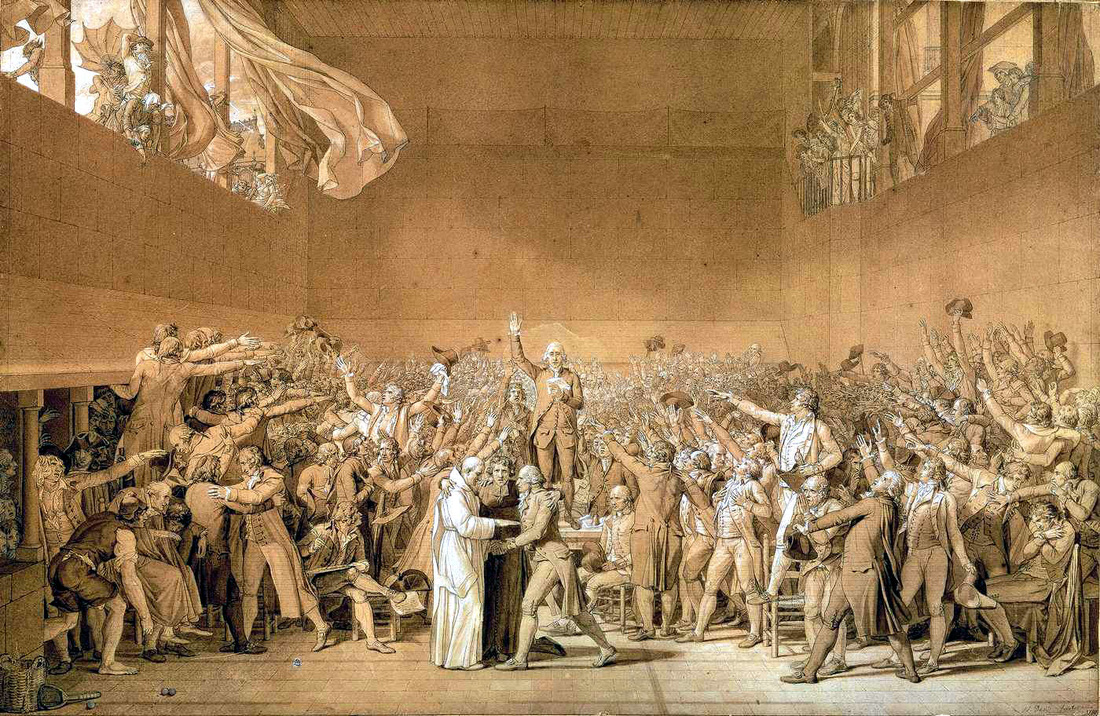

Gironde and Mountain, 1792-1793 | The French Revolution

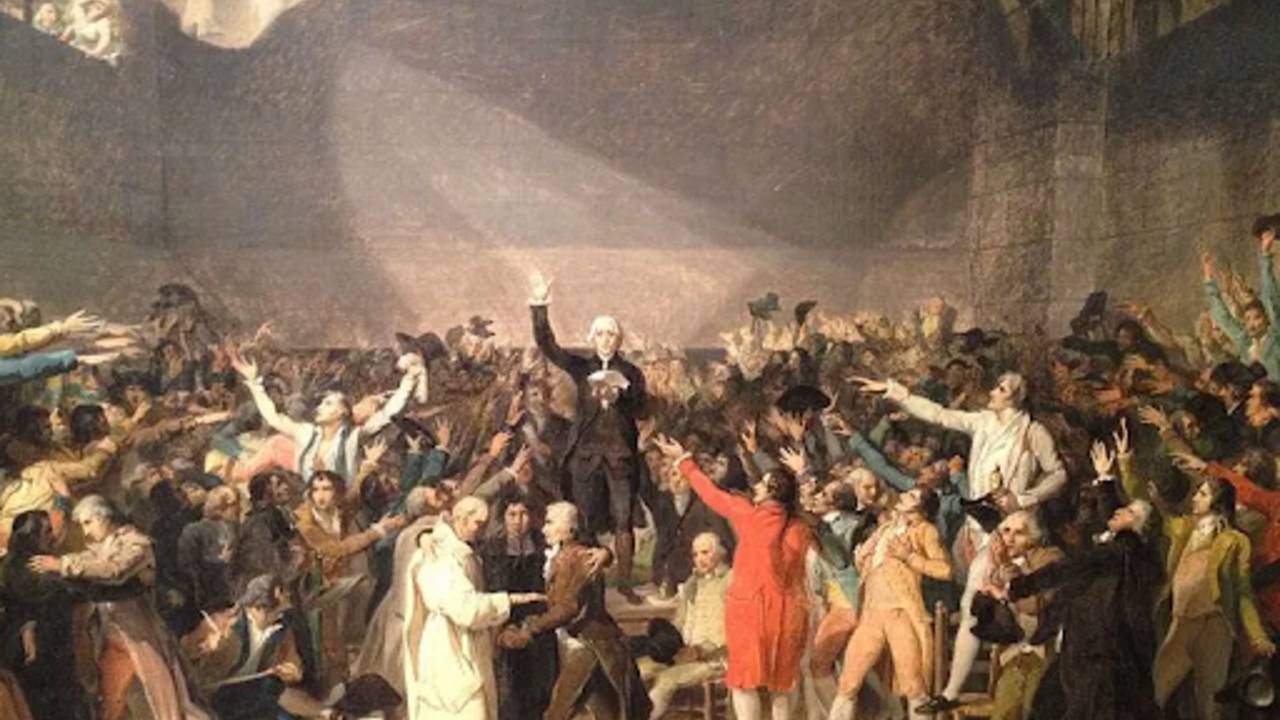

In theory the election of deputies to the National Convention in 1792 marked the beginning of political democracy in France. Virtually all male citizens were invited to the polls. Yet only 10 percent of the potential electorate of 7 million actually voted; the rest abstained or were turned away from the polls by the watchdogs…

-

The First Republic | The French Revolution

The weeks between August 10 and the meeting of the Convention on September 21 were a time of extreme tension. The value of the assignats depreciated by 40 percent during August alone. Jacobin propagandists, led by Jean Paul Marat (1743-1793), an embittered Swiss physician turned journalist, continually excited the people of Paris. Excitement mounted still…

-

The Legislative Assembly | The French Revolution

On October 1 the first and only Legislative Assembly elected under the new constitution began deliberations. No one faction commanded a majority in the new Assembly, though the Center had the most seats. Since they occupied the lowest seats in the assembly hall, the deputies of the center received the derogatory nickname of the Plain…

-

The Constitution of 1791 | The French Revolution

The major undertaking of the National Assembly was the Constitution of 1791. To replace the bewildering complex of provincial units that had existed under the Old Regime, the Assembly divided the territory of France into eighty-three departments of approximately equal size; the departments were subdivided into arrondissements, or “districts,” and the districts into communes—that is,…

-

Reforming the Church | The French Revolution

Since the suppression of tithes and the seizure of ecclesiastical property deprived the church of its revenue, the National Assembly agreed to finance ecclesiastical salaries. The new arrangement made the French church subject to constant government regulation. Few difficulties arose from the Assembly’s prohibition of monastic vows or from the liquidation of some monasteries and…

-

Women’s Rights in the French Revolution

Olympe de Gouges (b. 1748) was a leading female revolutionary. A butcher’s daughter, she believed that women had the same rights as men, though these rights had to be spelled out in terms of gender. In 1791 she wrote her Declaration of the Rights of Women and for the next two years demanded that the…

-

Forging a New Regime | The French Revolution

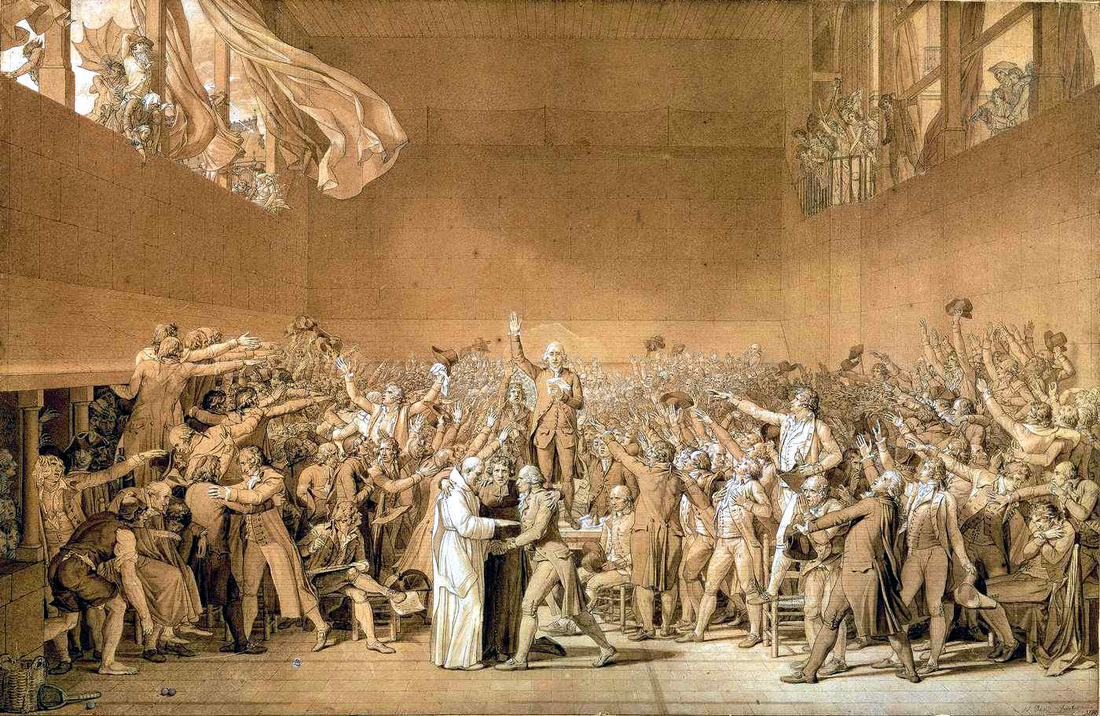

The outlines of the new regime were already starting to take shape before the October Days. The Great Fear prompted the National Assembly to abolish in law what the peasants were destroying in fact. On the evening of August 4, 1789, the deputies voted that taxation would be paid by all inhabitants of the kingdom…

-

Popular Uprisings, July-October 1789 | The French Revolution

Reaction to Necker’s dismissal was immediate. On July 12 and 13 the Parisian electors formed a new municipal government and a new militia, the National Guard, both loyal to the National Assembly. Paris was forging the weapons that made it the leader of the Revolution.

-

The Dissolution of the Monarchy | The French Revolution

The National Assembly had barely settled down to work when a new wave of rioting swept over France, further undermining the position of the king. Economic difficulties grew more severe in the summer of 1789. Unemployment increased, and bread seemed likely to remain scarce and expensive, at least until after the harvest. Meanwhile, the commoners…

-

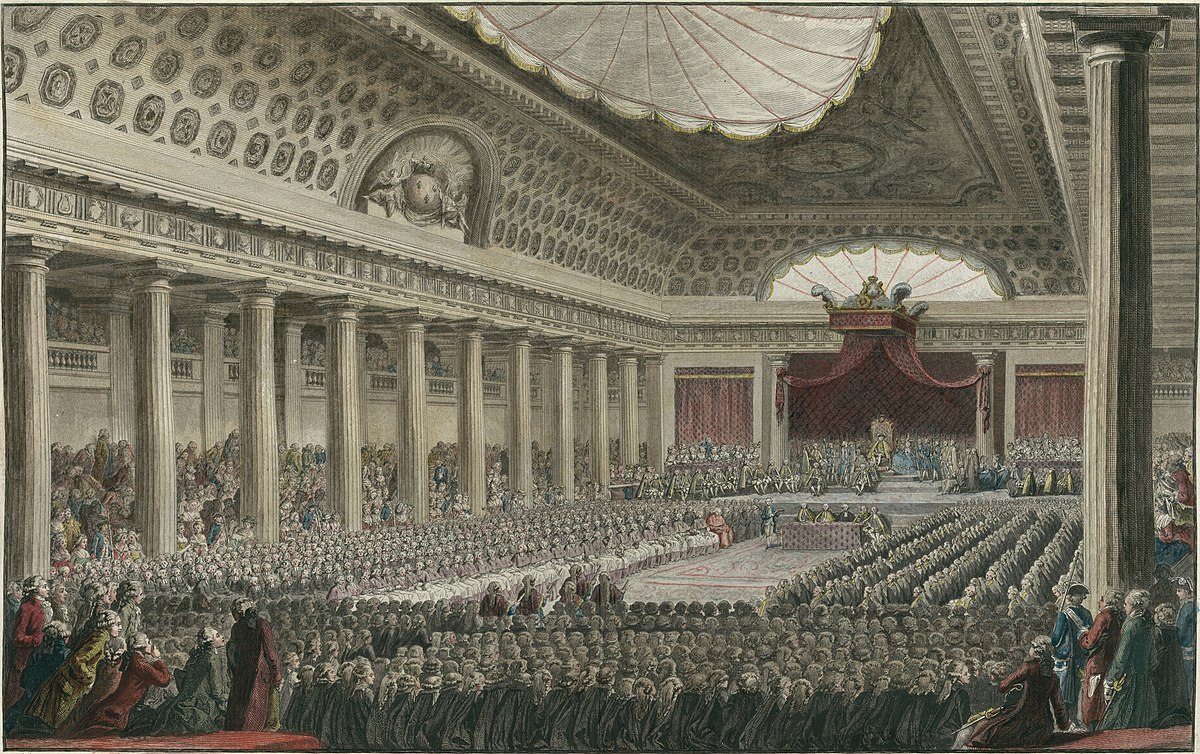

The Estates General, 1789 | The French Revolution

In summoning the Estates General Louis XVI revived a half-forgotten institution that he thought was unlikely to initiate drastic social and economic reforms. The three estates, despite their immense variation in size, had customarily received equal representation and equal voting power, so that the two privileged orders could be expected to outvote the commoners.

-

The Financial Emergency, 1774-1788 | The French Revolution

The chronic financial difficulties of the French monarchy strengthened the hand of the middle-class reformers. The government debt, already large at the accession of Louis XVI, tripled between 1774 and 1789. The budget for 1788 had to commit half the total estimated revenues to interest payments on debts already contracted; it also showed an alarming…

-

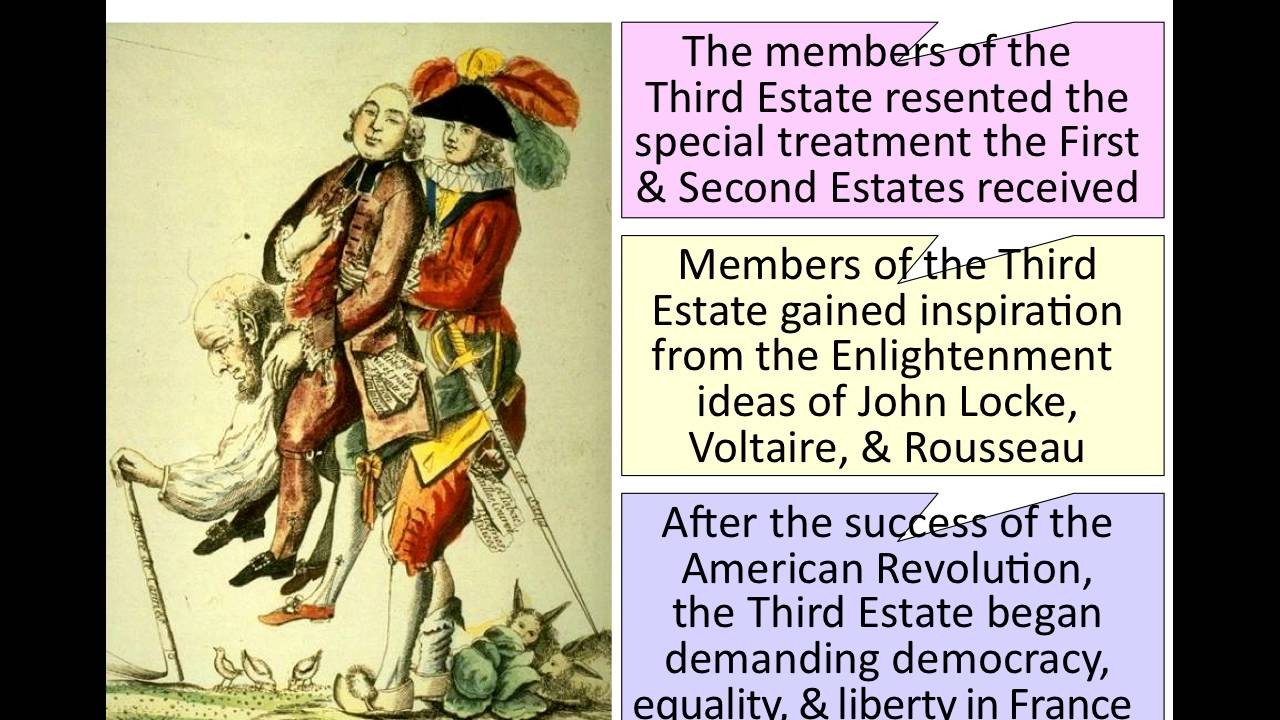

The Third Estate | The French Revolution

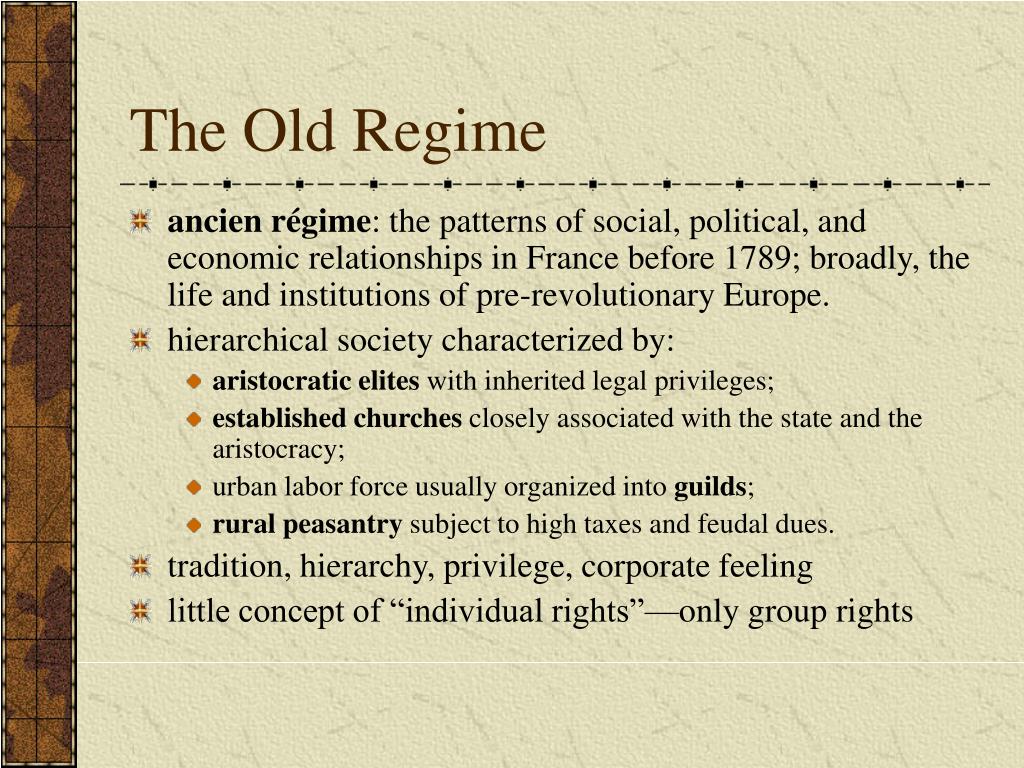

The first two estates included only a small fraction of the French nation; over 97 percent of the population fell within the third estate. Most of these commoners were peasants, whose status was in some respects more favorable in France than anywhere else in Europe. Serfdom, still prevalent in central and eastern Europe, had disappeared…

-

The Clergy and the Nobility | The French Revolution

The first estate, the clergy, occupied a position of conspicuous importance in France. Though only .5 percent of the population, the clergy controlled about 15 percent of French lands. They performed many essential public functions—running schools, keeping records of vital statistics, and dispensing relief to the poor. The French church, however, was a house divided.

-

The Causes of Revolution | The French Revolution

Honest, earnest, and pious, but also clumsy, irresolute, and stubborn, Louis XVI (r. 1774-1792) was most at home hunting, eating, or tinkering with locks. He also labored under the handicap of a politically unfortunate marriage to a Habsburg. Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), the youngest of the empress Maria Theresa’s sixteen children, was badly educated, extravagant, and…

-

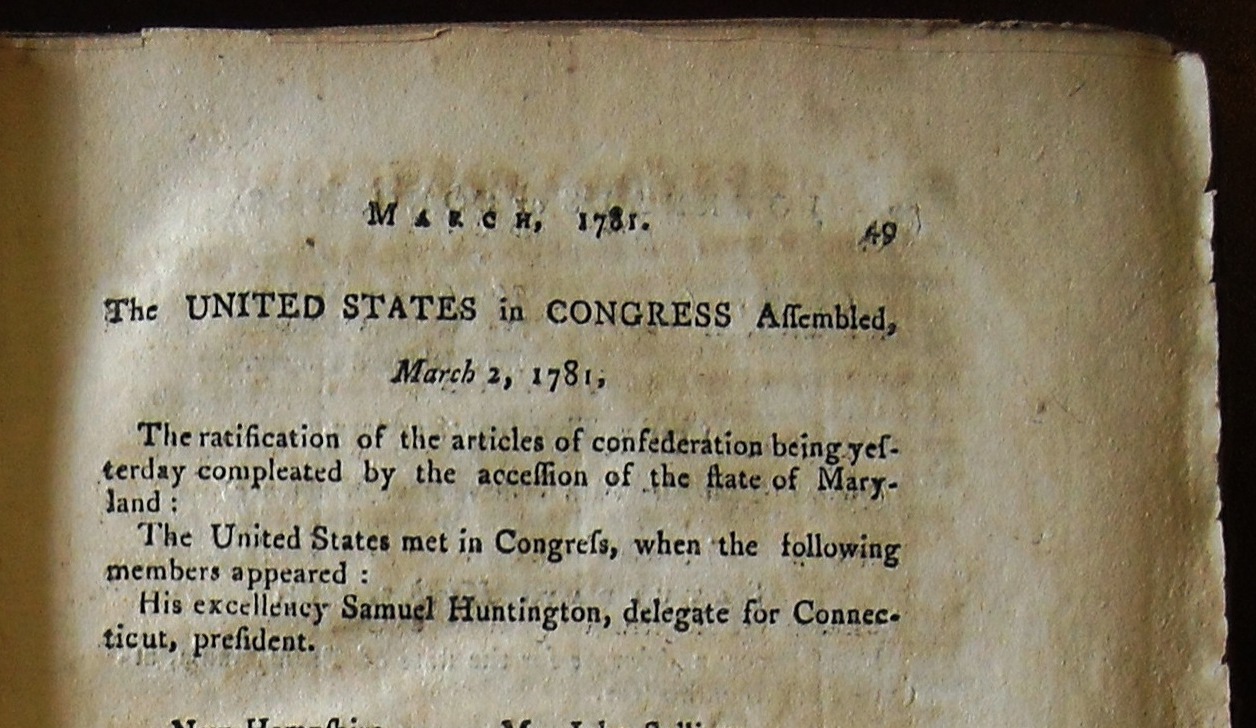

The French Revolution and Napoleon

In France, as in Britain’s North American colonies, a financial crisis preceded a revolution. There was not only a parallel but also a direct connection between the revolution of 1776 and that of 1789. French participation in the American War of Independence enormously increased an already excessive governmental debt. Furthermore, the example of America fired…

-

Summary | The Enlightenment

French cultural leadership in the eighteenth century was preeminent. The key concepts of the eighteenth-century philosophes, or intellectuals, were reason, natural law, and progress. Philosophes, who expressed optimism in human abilities to apply reason, owed a debt to John Locke for their ideas on government and human psychology. Under the direction of Diderot, philosophes produced…

-

Literature and the Arts | The Enlightenment

The literary landmarks of the century included both the classical writings of the French philosophes and the English Augustans, and new experiments in the depiction of realism and “sensibility,” that is, the life of the emotions. In England the Augustan Age of letters took its name from the claim that it boasted a group of…

-

Pietists and Methodists | The Enlightenment

The popular reaction, on the other hand, was an evangelical revival that began with the German Pietists. The Pietists asserted that religion came from the heart, not the head, and that God was far more than a watchmaker, more than the remote creator of the world-machine.

-

Challenges to the Enlightenment | The Enlightenment

The philosophes expected people to see reason when it was pointed out, to give up the habits of centuries, and to revise their behavior in accordance with natural law.

-

Implications of the Revolution | The Enlightenment

For the mother country the American Revolution implied more than the secession of thirteen colonies. It involved Britain in a minor world war that jeopardized its dominance abroad and weakened the power and prestige of King George III at home.

-

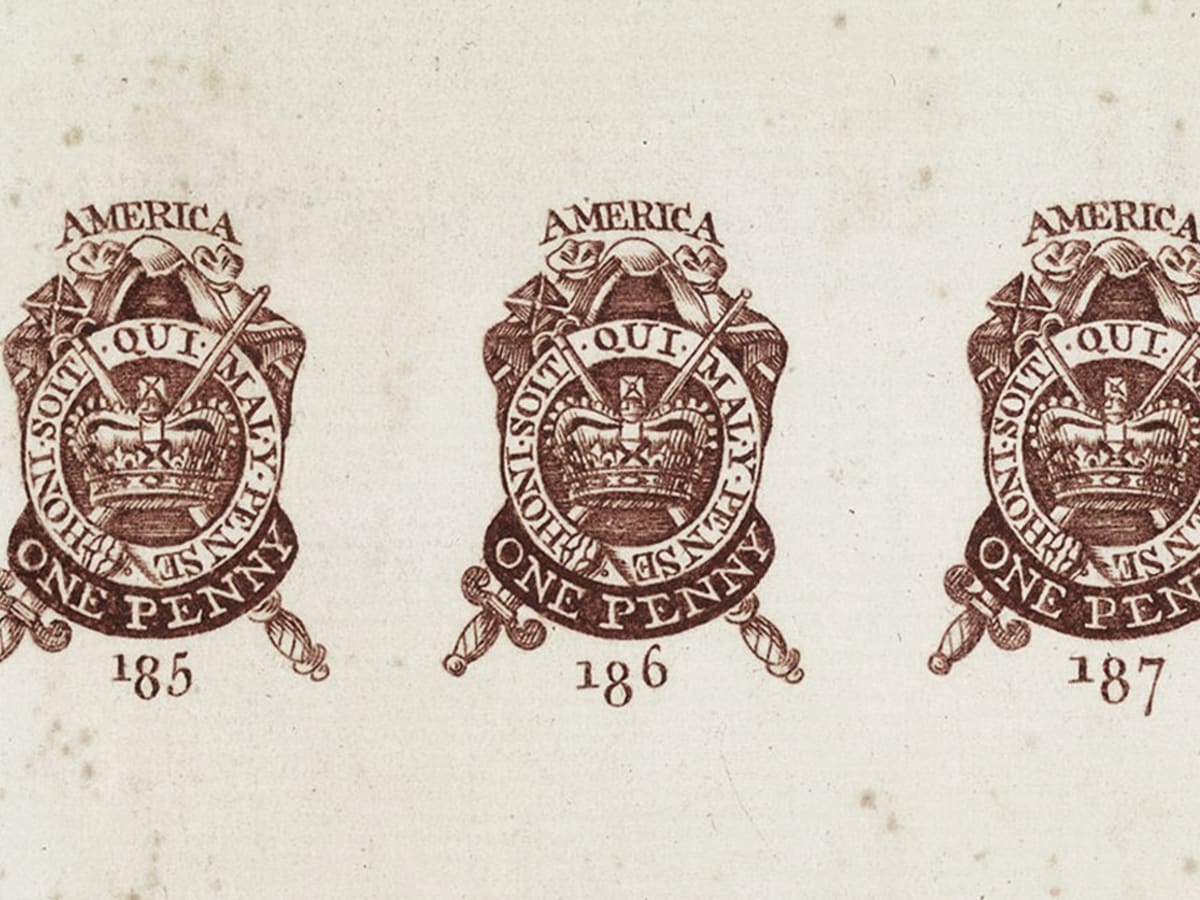

The Stamp Act Congress Asserts the Right of Local Representation

The Stamp Act Congress met in New York City in October 1765 and declared: That His Majesty’s liege subjects in these colonies are entitled to all the inherent rights and liberties of his natural born subjects within the kingdom of Great Britain. That it is inseparably essential to the freedom of a people, and the…

-

Background of the American Revolt, 1760-1776 | The Enlightenment

The breach between the colonies and Britain first became serious after the Seven Years’ War, when Britain began to interfere more directly and frequently in colonial matters. By 1763 the colonies had become accustomed to regulating their own affairs, though the acts of their assemblies remained subject to the veto of royally appointed governors or…

-

King George III and American Independence | The Enlightenment

Though Catherine the Great failed to apply the ideas of the Age of Reason, her name often appears on lists of enlightened despots. Another name is at times added to the list—George III, king of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820). George III tried to wrest control of the House of Commons from the long-dominant Whig oligarchy…

-

Foreign Policy, 1725-1796 | The Enlightenment

Between the death of Peter the Great and that of Catherine, Russian foreign policy still pursued the traditional goals of expansion against Sweden, Poland, and Turkey. But Russia found that these goals increasingly involved it with the states of central and western Europe. In the War of the Polish Succession (1733-1735) Russian forces were allied…

-

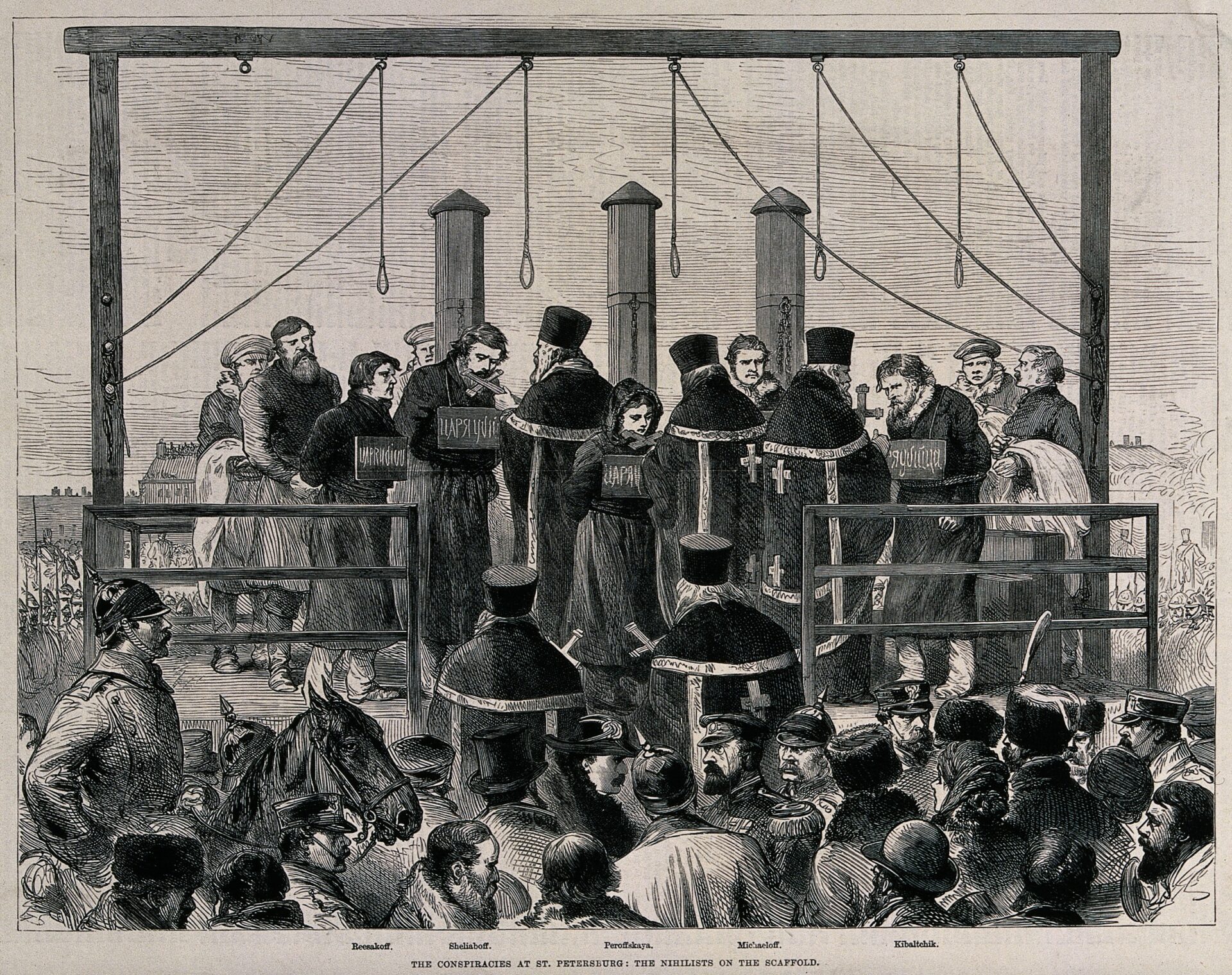

Paul, r. 1796-1801, and Alexander I, r. 1801-1825 | The Enlightenment

Catherine’s son Paul succeeded her in 1796 at age forty- two. He appeared to be motivated chiefly by a wish to undo his mother’s work. He exiled some of her favorites and released many of her prisoners. Paul’s behavior, however, was unpredictable. On the one hand, he imposed a strict curfew on St. Petersburg and…

-

Catherine the Great, 1762-1796 | The Enlightenment

Brought up in a petty German court, Catherine found herself transplanted to St. Petersburg as a young girl, living with a husband she detested, and forced to pick her way through the intrigues that flourished in the Russian capital.

-

Nobles and Serfs, 1730-1762 | The Enlightenment

In 1730 the gentry set out to emancipate themselves from the servitude placed upon them by Peter. By 1762 the nobles no longer needed to serve at all unless they wished to do so; simultaneously, the authority of noble proprietors over their serfs was increased. The former became the government’s agents for collecting the poll…

-

Russia, 1725-1825 | The Enlightenment

Russia had two sovereigns who could be numbered among the enlightened despots: Catherine II, the Great (r. 17621796) and her grandson Alexander I (r. 1801-1825). For the thirty-seven years between the death of Peter the Great and the accession of Catherine the autocracy was without an effective leader as the throne changed hands seven times.…

-

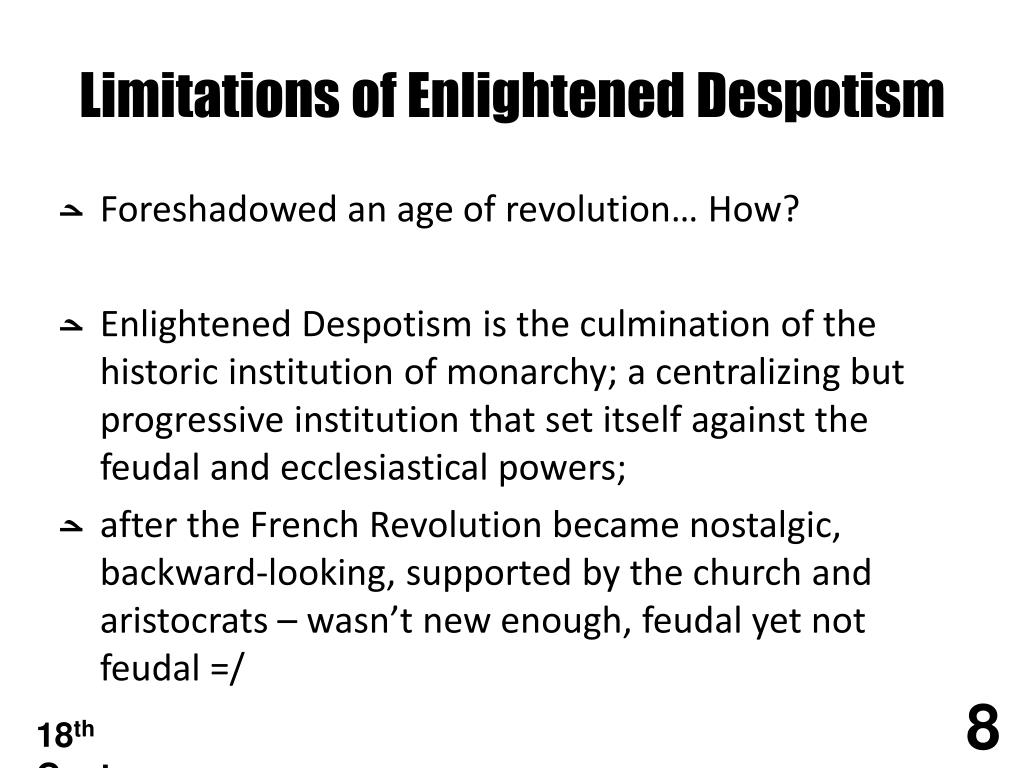

The Limitations of Enlightened Despotism | The Enlightenment

Enlightened despotism was impaired by the problem of succession. So long as monarchs came to the throne by the accident of birth, there was nothing to prevent the unenlightened or incapable from succeeding the enlightened and able. Even the least of the enlightened despots deserves credit for having reformed some of the bad features of…

-

Charles III, Pombal, Gustavus III, 1759-1792 | The Enlightenment

As king of Spain (r. 1759-1788), Charles III energetically advanced the progressive policies begun under his father, Philip V. Though a pious Catholic, Charles forced the Jesuits out of Spain. He reduced the authority of the aristocracy, extended that of the Crown, and made Spain more nearly a centralized national state.

-

Maria Theresa, Joseph II, Leopold II, 1740-1792 | The Enlightenment

Frederick’s decisive victory in the War of the Austrian Succession had laid bare the basic weaknesses of the Habsburgs’ dynastic empire. The empress Maria Theresa (r. 1740-1780) believed in the need for reform and often took as her model the institutions of her hated but successful rival, Frederick II of Prussia.

-

Frederick the Great, r. 1740-1786 | The Enlightenment

Of all the eighteenth-century rulers, Frederick II, the Great, king of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, appeared best attuned to the Enlightenment. As a youth he had rebelled against the drill-sergeant methods of his father, Frederick William I. An attentive reader of the philosophes, he exchanged letters with them and brought Voltaire to live for…

-

Enlightened Despots | The Enlightenment

The concept of an enlightened despot has proved attractive in many cultures. Those rulers who were versed in the thought of the Enlightenment, may have realized that great social and economic changes were at hand, but some were more adept than others in their understanding of these changes and of how best to prepare their…

-

The Beginning of "Modern History"

Identifying when modern history began is really only a matter of convenience. Modern history relates to the presence of activities and customs that seem less strange to us today than do certain very ancient customs. Consider the range of such changes. In the Renaissance astrology was an accepted branch of learning; religious objections to it,…

-

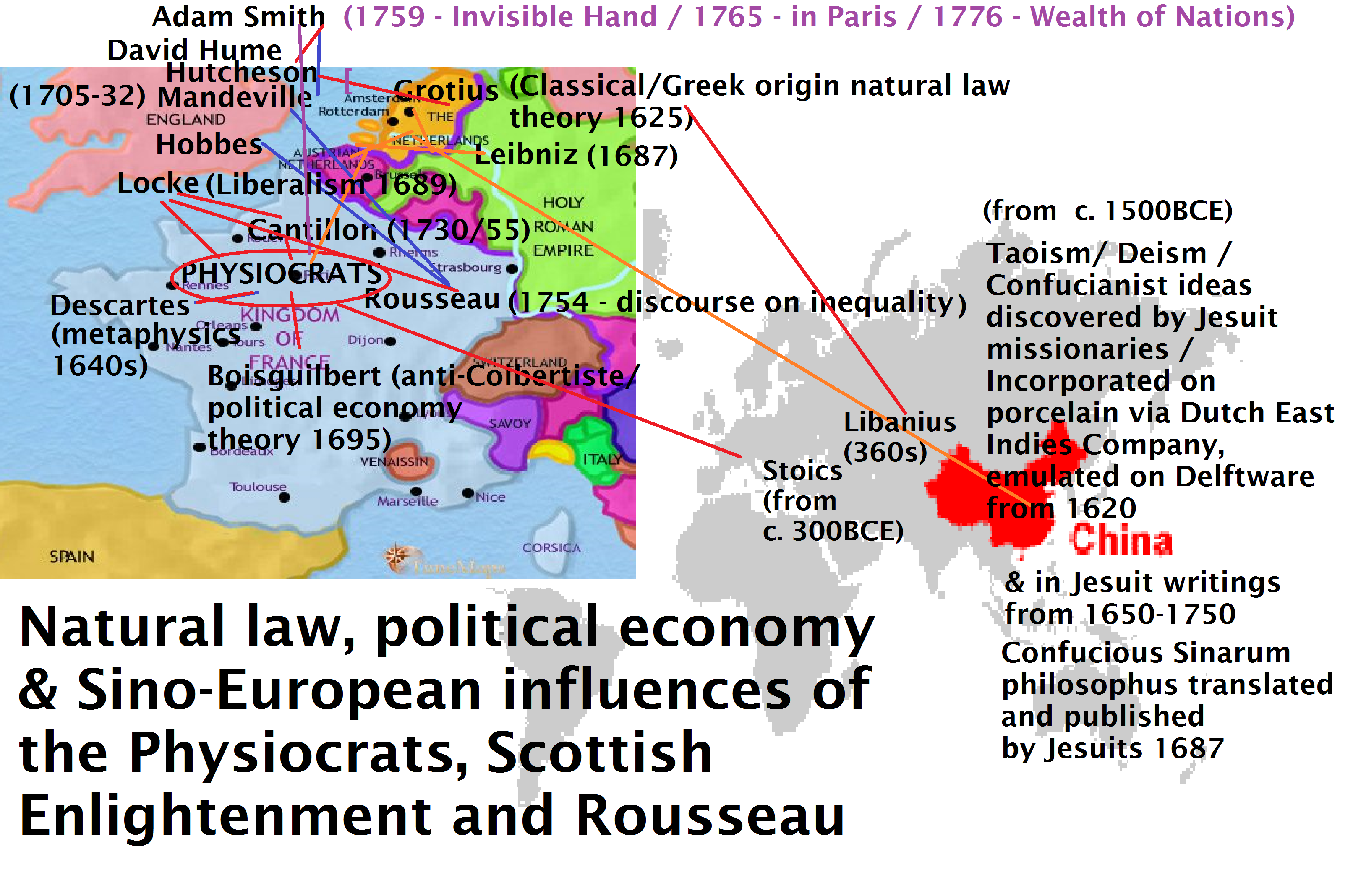

Political Thought | The Enlightenment

In The Spirit of the Laws (1748), the baron de la Brede et de Montesquieu (1689-1755), an aristocratic French lawyer and philosophe, laid down the premise that no one system of government suited all countries. Laws, he wrote, should be in relation to the climate of each country, to the quality of its soil, to…

-

The Attack on Religion | The Enlightenment

Attacks on clerical teaching formed part of a vigorous body of criticism of the role of the clergy in the Old Regime. In denouncing fanaticism and superstition, the philosophes singled out the Society of Jesus.

-

Adam Smith on Free Trade

Adam Smith extended the theory of natural liberty to the realm of economics, formulating the classic statement in favor of free trade. It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy. The taylor does not…

-

Justice and Education | The Enlightenment

The disposition to let nature take its course also characterized the outlook of the philosophes on questions of justice. They believed that legislation created by humans prevented the application of the natural laws of justice. They were horrified by the cumbersome judicial procedures of the Old Regime and by its antiquated statutes. New lawgivers were…

-

Laissez-Faire Economics | The Enlightenment

The economic program of the philosophes was introduced in articles written for the Encyclopedic by the versatile Francois Quesnay (1694-1774), biologist, surgeon, and personal physician to the French court. Quesnay headed a group of publicists who adopted the name Physiocratsbelievers in the rule of nature. The Physiocrats expected that they would, as Quesnay claimed, discover…

-

French Leadership | The Enlightenment

The cosmopolitan qualities of the century were expressed in the Enlightenment. Yet the Age of Reason also marked the high point of French cultural leadership, when, as Thomas Jefferson put it, every man had two homelands, his own and France.

-

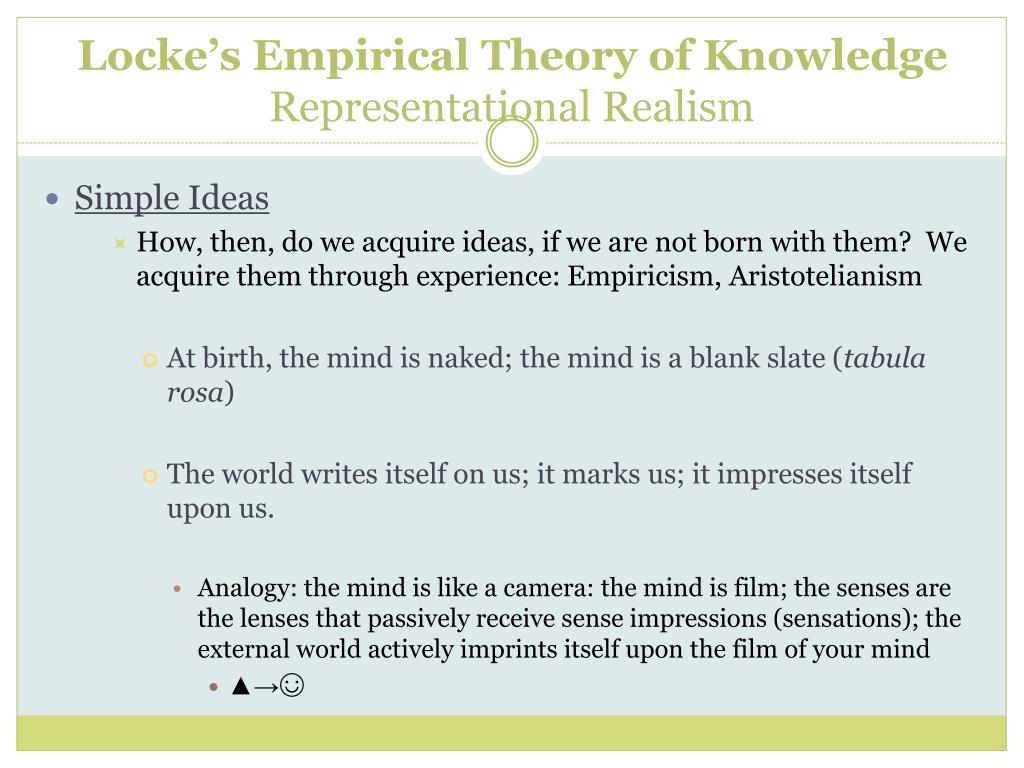

Locke’s Theory of Knowledge

In the age-old debate as to the most formative influences on an individual’s life—heredity or environment—and the most significant tool for comprehending either—faith or reason—John Locke came down squarely in favor of environment and reason.

-

The Philosophes and their Program of Reform, 1690-1776 | The Enlightenment

The philosophes hailed improvements in industry and agriculture and the continued advance of science. A Swedish botanist and physician, Carolus Linnaeus (Carl von Linne, 1707-1778), proposed a system for classifying plants and animals by genus and species, which biologists still follow today.

-

The Enlightenment

Reason, Natural Law, Progress – these are the words by the eighteenth century. It was the Age of Enlightenment, when it was widely assumed that human reason could cure past ills and help achieve utopian government, perpetual peace, and a perfect society. Reason would enable humanity to discover the natural laws regulating existence and thereby…

-

Summary | The Old Regimes

The Old Regime, the institutions that existed in France and Europe before 1789, exhibited features of both the medieval and early modern worlds. The economy was largely agrarian, but in western Europe serfdom had disappeared. The social foundations of the Old Regime were based on three estates. Increasingly, the economic, social, and political order of…

-

The International Balance in Review | The Old Regimes

The peace settlements of Hubertusburg and Paris ended the greatest international crisis that was to occur between the death of Louis XIV and the outbreak of the French Revolution. New crises were to arise, but they did not fundamentally alter the international balance; they accentuated the shifts that had long been underway. And although American…

-

The Diplomatic Revolution and the Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763 | The Old Regimes

In Europe the dramatic shift of alliances called the Diplomatic Revolution immediately preceded the formal outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, which had already begun in the colonies. Britain, which had joined Austria against Prussia in the 1740s, now paired off with Frederick the Great. And in the most dramatic move of the Diplomatic Revolution,…

-

The Austrian Succession, 1739-1748 | The Old Regimes

Britain and France collaborated in the 1720s and 1730s because both Walpole and Fleury sought stability abroad to promote economic recovery at home. The partnership, however, collapsed over the competition between the two Atlantic powers for commerce and empire. Neither Walpole nor Fleury could prevent the worldwide war between Britain and the Bourbon monarchies that…

-

The Turkish and Polish Questions, 1716-1739 | The Old Regimes

In 1716 the Ottoman Empire became embroiled in a war with Austria that resulted in the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718), by which Charles VI recovered the portion of Hungary still under Turkish rule, plus some other Ottoman lands in the Danube valley. Another Austro Turkish war (1735-1739) modified the Passarowitz settlement.

-

War and Diplomacy, 1713-1763 | The Old Regimes

In the early eighteenth century the international balance was precarious. Should the strong states decide to prey upon the weak, the balance was certain to be upset. One such upset resulted from the Great Northern War, which enabled Russia to replace Sweden as the dominant power in the Baltic.

-

The Polish and Ottoman Victims | The Old Regimes

By the early eighteenth century, Poland and the Ottoman Empire still bulked large on the map, but both states suffered from incompetent government, a backward economy, and the presence of large national and religious minorities. The Orthodox Christians in Catholic Poland and Muslim Turkey were beginning to look to Russia for protection.

-

Peter the Great

Interpretations of Peter the Great vary enormously. Voltaire considered him to be the model of the “enlightened despot.” Nicolai M. Karamzin (1766-1826), who was Russia’s first widely read novelist, attacked the Petrine myth and argued that Peter was subverting traditional Russian values:

A History of Civilization