Possessed of inquiring, speculative minds, and interested in their environment, the Greeks were keenly interested in science. Stimulated by their acquaintance with Egypt, they correctly attributed many of the workings of nature to natural rather than supernatural causes. They knew that the Nile flooded because annual spring rains caused its source in Ethiopia to overflow. They decided that the straits between Sicily and Italy and between Africa and Spain were the result of earthquakes. They understood what caused eclipses and knew that the moon shone by light reflected from the sun.

Hippocrates of Cos (c. 460-c. 377) founded a school of medicine from which there survive the Hippocratic oath and detailed clinical accounts of the symptoms and progress of diseases so accurate that modern doctors have been able to identify cases of epilepsy, diphtheria, and typhoid fever. The mathematician Pythagoras (c. 580-500) seems to have begun as a musician interested in the mathematical differences in the length of lyre strings needed to produce various notes.

The theorem that in a right triangle the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides we owe to the followers of Pythagoras. They made the concept of numbers into a guide to the problems of life, elevating mathematics almost to a religious cult. Pythagoras is said to have been the first to use the word cosmos—”harmonious and beautiful order”—for the universe. Earlier Greeks had found the key to the universe in some single primal substance: water, fire, earth, or air. Democritus (c. 460-370) decided that all matter consisted of minute, invisible atoms.

When Alexandria became the center of scientific research, the astronomer Aristarchus, in the mid-third century B.C., concluded that the earth revolves around the sun. His younger contemporary, Eratosthenes, believed that the earth was round and estimated its circumference quite accurately. Euclid, the great geometrical systematizer, had his own school at Alexandria in the third century B.C. His pupil Archimedes won a lasting reputation in both theoretical and applied physics, devising machines for removing water from mines and irrigation ditches and demonstrating the power of pulleys and levers by single-handedly drawing ashore a heavily laden ship. Hence his celebrated boast: “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand on, and I will move the world.” In the second century, Hipparchus calculated the length of the solar year to within a few minutes.

Rhetoric also became an important study, as the Greeks reflected on the construction of their own language and developed high standards of self-expression and style. The subject began with political oratory, as each leader strove to be more eloquent than the last. But to speak effectively, one must have something to say, and a body of professional teachers, who wrote on physics, astronomy, mathematics, logic, and music, traveled about, receiving pay. These multipurpose scholars who in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. taught people how to talk and write and think on all subjects were called Sophists (wisdom men). Sophists generally tended to be highly skeptical of accepted standards of behavior and morality, questioning the traditional ways of doing things.

How could anybody really be sure of anything, they would ask? And some would answer that we cannot know anything we cannot experience through one of our five senses. How could one be sure that the gods existed if no one could see, hear, smell, taste, or touch them? If there were no gods and therefore no divine laws, how should we behave? Should we trust laws made by others like ourselves? And what sort of men were making the laws, and in whose interest? Perhaps all existing laws were simply a trick invented by powerful people to protect their position.

Maybe the general belief in the gods was simply encouraged and expanded by clever people in whose interest it was to have the general public docile. Not all Sophists went this far, but in Athens during the Peloponnesian War many young people, troubled by the war or by the sufferings of the plague, were ready to listen to suggestions that the state should not make such severe demands upon them. Many citizens, gods fearing and law abiding, saw the Sophists as corrupters of youth.

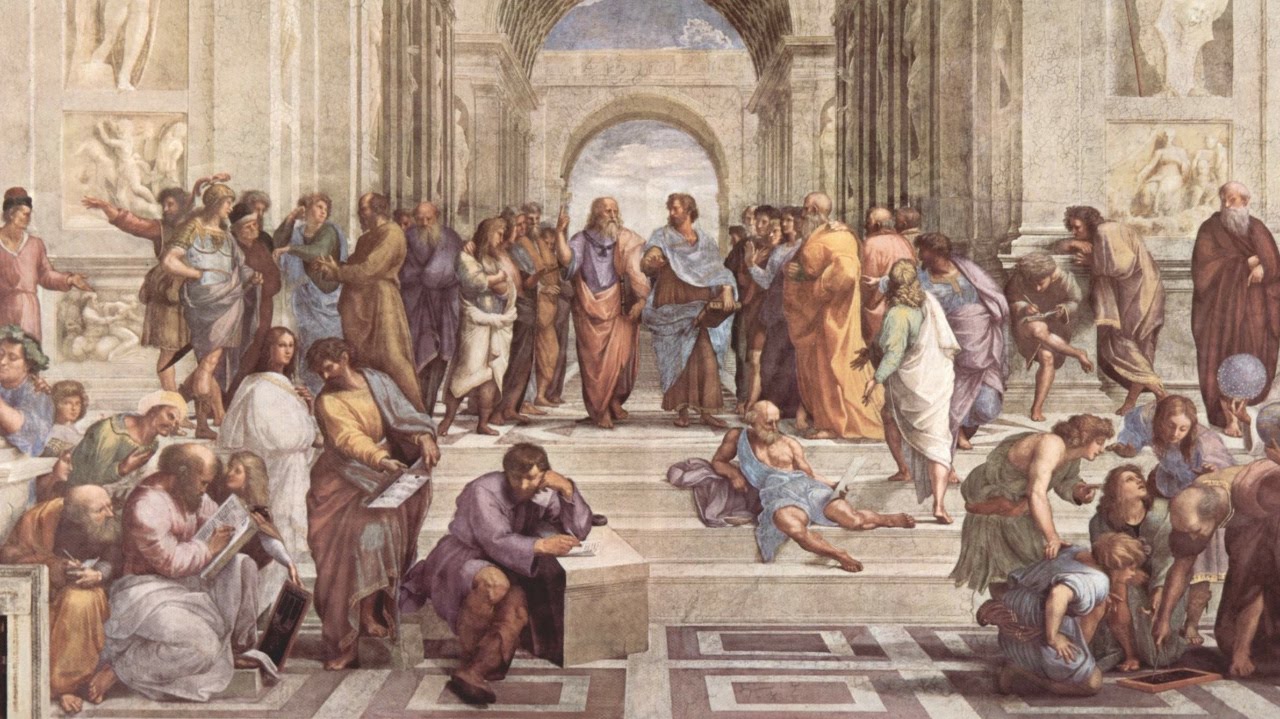

It is only against this background that we can understand the career and fate of Socrates (469-399 B.C.), whose method (though not affiliation) was that of the Sophists-to question everything, all current assumptions about religion, politics, and behavior-but who retained unwavering to the end his own deep inner loyalties to Athens. Though Socrates wrote no books, we know him well from contemporary reports, chiefly those of his pupil Plato (c. 427-347). Socrates was a stonemason who spent his life arguing in the assembly, in public places, and in the homes of his friends in Athens. He thought of himself as a gadfly, challenging everything anybody said to him and urging people not to take their preconceptions and prejudices as truths. Only never-ending debate, a process of question and answer could lead human beings to truth.

At about age seventy, Socrates was brought to trial on charges of disrespect to the gods and corrupting the young men of Athens. He argued that he had followed the prescribed religious observances and that he only wanted to make the young men better citizens; he defended his gadfly tactics as necessary to stir a sluggish state into life. But by a narrow margin, a court of 501 jurors voted the death penalty. Socrates drank the poison cup of hemlock and waited for death, serenely optimistic.

Thereafter, it was Plato who carried on his work. Plato founded a school in Athens, the Academy, and wrote several notable dialogues, intellectual conversations in which Socrates and others were shown discussing problems of life and the human spirit. Much influenced by the Pythagoreans, Plato retained a deep reverence for mathematics, but he found cosmic reality in Ideas rather than in numbers. As each person has a “true self” within and superior to the body, so the world we experience with our bodily senses has within and superior to itself a “true world”-an invisible universe or cosmos.

In The Republic, Plato has Socrates compare the relationship between the world of the senses and the world of Ideas with that between the shadows of persons and objects as they would be cast by firelight on the wall of a cave, and the same real persons and objects as they would appear in the direct light of day. People see objects-chairs, tables, trees-of the world as real, whereas they are only reflections of the true realities-the Ideas of the perfect chair, table, or tree. So human virtues are reflections of ideal virtues, of which the highest is the Idea of the Good. Human beings can, and should, strive to know the ultimate Ideas, especially the Idea of the Good.

Politically, Athenian democracy did much to disillusion Plato: He had seen its courts condemn his master. On his travels he had formed a high opinion of the tyrants ruling the Greek cities of Sicily and Italy. So when Plato came to sketch the ideal state in The Republic, his system resembled that of the Spartans. He recommended that power be entrusted to the Guardians, a small intellectual elite, specially bred and trained to understand Ideas, governing under the wisest man of all, the Philosopher-King. The masses would simply do their jobs as workers or soldiers and obey their superiors. Democracy, he concluded, by relying on amateurs, was condemned to failure through the fatal flaws in the character of those who would govern.

Plato’s most celebrated pupil was Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), called the “master of those who know.” Son of a physician at the court of Philip of Macedon and tutor to Alexander the Great, Aristotle was interested in everything. He wrote on biology, logic, ethics, literary criticism, political theory. His work survives largely in the form of notes on his lectures taken by his students. Though he wrote 158 studies of the constitutions of Greek cities, only the study of Athens survives. Despite their lack of polish, these writings have had enormous influence.

The first to use scientific methods, Aristotle classified living organisms into groups, much as modern biologists do, and extended the system to other fields- government, for example. He maintained that governments were of three forms-rule by one man, rule by a few men, or rule by many men-and that there were good and bad types of each, respectively monarchy and tyranny, aristocracy and oligarchy, polity and mob rule. Everywhere-in his Logic, Poetics, and Politics-he laid foundations for later inquiry. Though he believed that people should strive and aspire, he did not push them on to Socrates’ goal of self-knowledge or Plato’s lofty ascent to the Idea of the Good. He urged instead the cultivation of the Golden Mean, the avoidance of excess on either side-courage, not foolhardiness or cowardice; temperance, not overindulgence or abstinence; liberality in giving, not prodigality or meanness.

Later, in the period after Alexander, two other schools of Hellenic philosophy developed, the Epicurean and the Stoic. Epicurus (341-271) counseled temperance and reason, carrying further the principle of the Golden Mean. Though he defined pleasure as the key to human happiness, he ranked spiritual joys above those of the body, which he recommended should be satisfied in moderation. Although the gods existed, he taught that they did not interest themselves in human affairs. The Stoics, founded by Zeno (c. 333-262) got their name from the columned porch (Stoa) in the Athens agora from which he first taught. They preferred to repress the physical desires altogether. Since only the inward divine reason counted, the Stoics preached total disregard for social, physical, or economic differences. They became the champions of slaves and other social outcasts, anticipating to some degree one of the moral teachings of Christianity.