The process of industrialization began in Britain. After the 1760s England enjoyed a long period of relative economic prosperity. Starting in the sixteenth century, a new group of landed proprietors—squires and townspeople— saw land as an investment; thus they were concerned with improved production and profit.

The enclosure movement had, in effect, transformed estates into compact farms, set off from others by fences or hedgerows. Marginal cottagers and garden farmers were eliminated, landowners were freed from manorial restrictions on farming practices, and the division of markets and of labor stimulated individual and geographically localized productivity.

A sharp rise in the price of grain, caused by wars and by industrialization in local centers such as Manchester, meant that more land was put into crops, leading to a greater demand for labor. Waste lands were put into production for vegetable crops to feed to animals, and eastern England in particular became a center of experimentation with new fertilizers, crops, and methods of crop rotation.

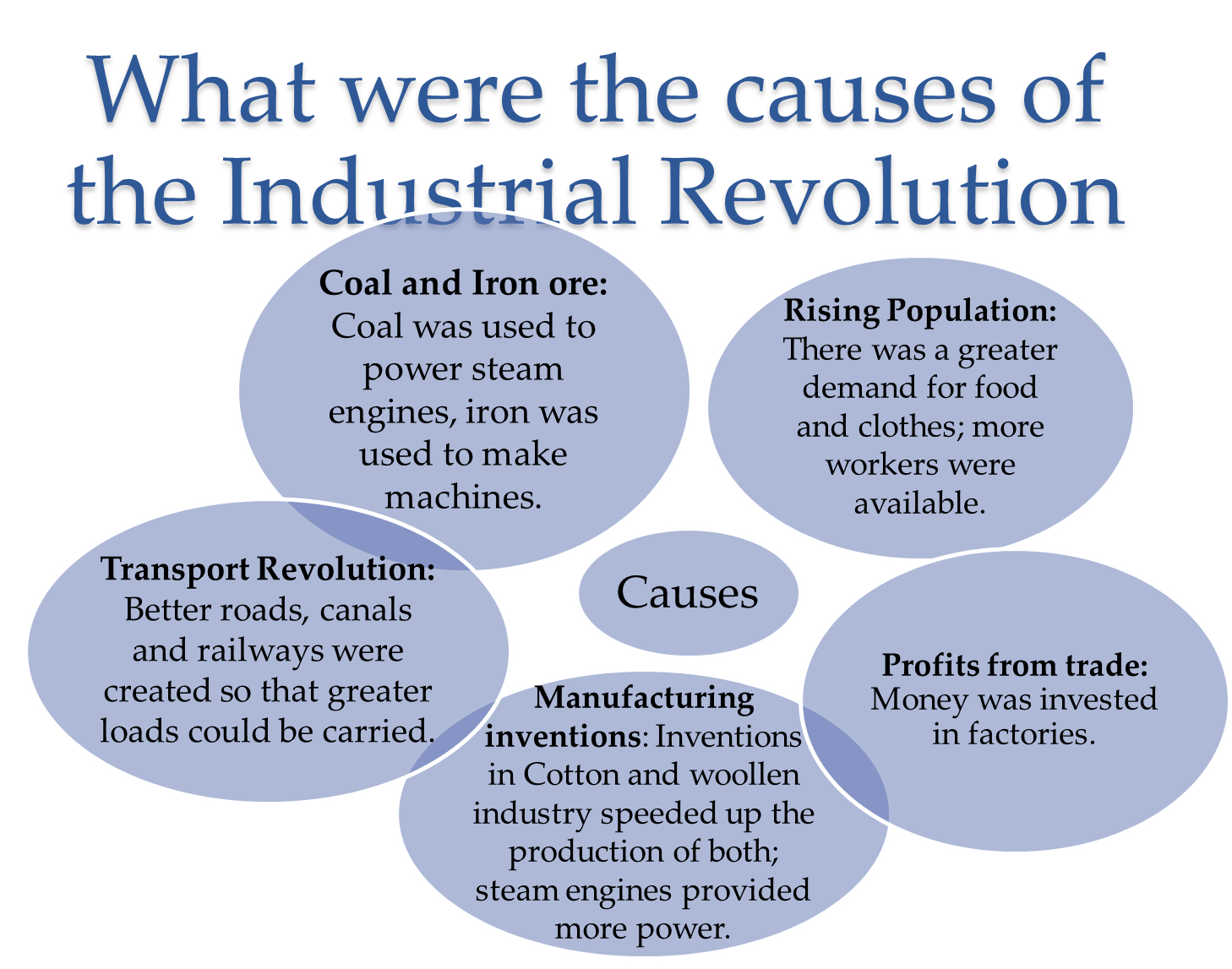

Wealthy, aristocratic proprietors adopted the new methods and also financed canals, roads, mines, and eventually railroads to carry their produce to market. Increased productivity led to a rapid growth in population in England and Wales—from 7.5 million in 1751 to 21 million in 1851—creating a large pool of workers for the new industries.

England’s good fortune was enhanced not only by ample supplies of capital from foreign and colonial trade but also by the possession of large deposits of coal and iron. The geographical compactness of the British Isles made shipments from mine to smelter and from mill to seaport short, fast, and cheap. The marginal farmers, and also the Irish, driven from their overpopulated and famine- ridden island, formed a large reservoir of eager labor. The Napoleonic wars further stimulated the demand for metal goods and the invention of new machines.

Thus the twin needs of economic activity—labor and capital—were met. The rising population became a market for simple manufactured goods while also supplying labor. Women and children were employed, especially in the textile industries, because they could be paid less and were suited to jobs requiring dexterity of hand and eye rather than a strong back.

The large landowners had capital to spare, and from their ranks, and even more from the ranks of the middle class, came the entrepreneurs. The middle class enjoyed a secure social status, partly as a result of the law of primogeniture by which land passed undivided to the eldest son.

Since second sons, gentlemen in birth and education, could not inherit the estate, they could enter trade, the military, the church, and the colonial service without serious social stigma.