The economic developments of the early nineteenth century had rendered the system of serfdom less and less profitable. In the south, where land was fertile and crops were produced for sale as well as for use, the serf usually tilled his master’s land three days a week, but sometimes more. In the north, where the land was less fertile and could not produce a surplus, the serfs often had a special arrangement with their masters called quit-rent.

This meant that the serf paid the master annually in cash instead of in work, and usually had to labor at home as a craftsman or go to a nearby town and work as a factory hand or small shopkeeper to raise the money. As industries grew, it became clear to factory owners, who experimented with both serf and free labor, that serf labor was not as productive. Yet free labor was scarce, and the growing population needed to be fed.

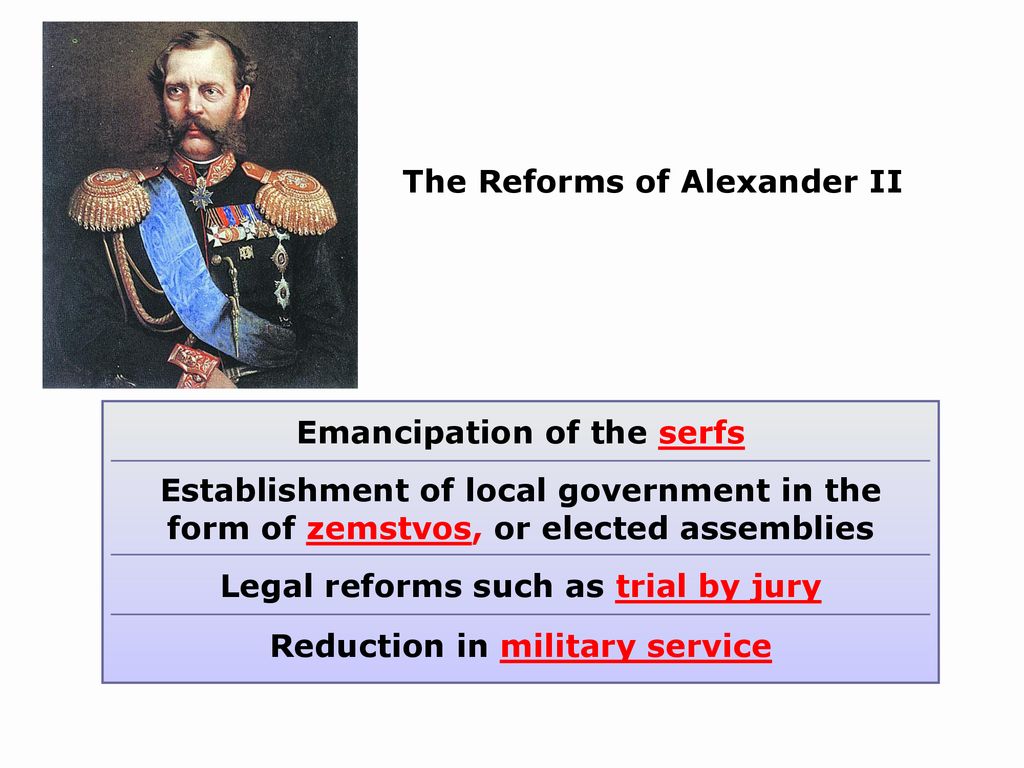

Serfdom had become uneconomic. But this fact was not widely recognized among Russian landowners. The nobility wished to keep things as they were and did not as a class feel that emancipation was the answer. Yet the serfs showed increasing unrest. Alexander II, though personally almost as conservative as his father, determined to embark on reforms, preferring, as he put it, that the abolition of serfdom come from above rather than from below.

Through a cumbersome arrangement in which local commissions made studies and reported their findings to members of the government, an emancipation law was eventually proclaimed early in 1861. A general statute declared that the serfs were now free, laid down the principles of the new administrative organization of the peasantry, and set out the rules for the purchase of land.

All peasants, crown and private, were freed, and each peasant household received its homestead and a certain amount of land, usually the amount the peasant family had cultivated for its own use in the past.

The land usually became the property of the village commune, or obshchina, which had the power to redistribute it periodically among the households. The government bought the land from the proprietors, but the peasants had to redeem it by payments extending over a period of forty-nine years. The proprietor retained only the portion of his estate that had been farmed for his own purposes.

This statute, liberating more than 40 million human beings, has been called the greatest single legislative act in history. But there were grave difficulties inherent in so sweeping a change in the nature of society. The peasant had to accept the allotment, and since his household became collectively responsible for the taxes and redemption payments, his mobility was not greatly increased. The commune took the place of the proprietor. Moreover, most peasants felt that they got too little land and had to pay too much for it.

The end of the landlords’ rights of control and police authority on their estates made it necessary to reform local administration. By statute in 1864, provincial and district assemblies, or zemstvos, were created. Chosen by an elaborate electoral system that divided the voters into categories by class, the assemblies gave substantial representation to the peasants.

The zemstvos dealt with local finances, education, medical care, scientific agriculture, maintenance of the roads, and other economic and social questions. Starting from scratch in many cases, the zemstvos made great advances in primary education and in improving public health. They led tens of thousands of Russians to hope that this progressive step would be crowned by the creation of a central parliament, or duma. But the duma was not granted, partly because, after an attempted assassination of the czar in 1866, the regime swung away from reform.

But before this happened, other advances had been made. The populations of the cities were given municipal assemblies, with duties much like those of the zemstvos in the countryside. The antique Russian judicial system and legal procedure were modernized. For the first time juries were introduced, cases were argued publicly and orally, and all classes were made equal before the law. Censorship was relaxed, and the often brutal system of military service was reformed and rendered less severe.

In foreign policy, Alexander II’s record was uneven. The Russians successfully repressed the Polish uprising of 1863. They seized the opportunity provided by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and simply tore up the Black Sea provisions of the Treaty of Paris, declaring unilaterally that they would no longer be bound by them. In 1877 the Russians went to war against Turkey once again, now on behalf of the rebellious Balkan Christians of Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Bulgaria.

By the Peace of San Stefano Russia obtained a large, independent Bulgarian state. But the powers—England, France, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Russia—at the Congress of Berlin later in the same year reversed the judgment of San Stefano. They permitted only about half of the planned Bulgaria to come into existence as an autonomous state, while another portion obtained autonomy separately as East Rumelia and the rest went back to Turkey.

Meanwhile, encroachments begun under Nicholas I against Chinese territory in the Amur River Valley remained undeflected by the Crimean War, and Russian gains were confirmed by the Treaty of Peking in 1860. Russian settlements in the “maritime province” on the Pacific Ocean continued to flourish, and Vladivostok was founded in 1858 and grew rapidly. In central Asia a series of campaigns conquered the Turkish khanates by 1896 and added much productive land to the Crown.

Here, however, the advance toward the northwest frontier of India appeared to threaten British interests and aroused public opinion in Britain against Russia, and after a brutal conquest of the Turkomans in 1881, the Russian Empire was, for the time, complete.