Lenin died in January 1924. During the last two years of his life, he played an ever-lessening role. Involved in the controversy over NEP was also the question of succession to Lenin.

Thus an answer to the questions of how to organize industry, what role to give organized labor, and what relations to maintain with the capitalist world depended not only upon an estimate of the actual situation but also upon a guess as to what answer was likely to be politically advantageous. From this maneuvering the secretary of the Communist party, Joseph Stalin, was to emerge victorious by 1928.

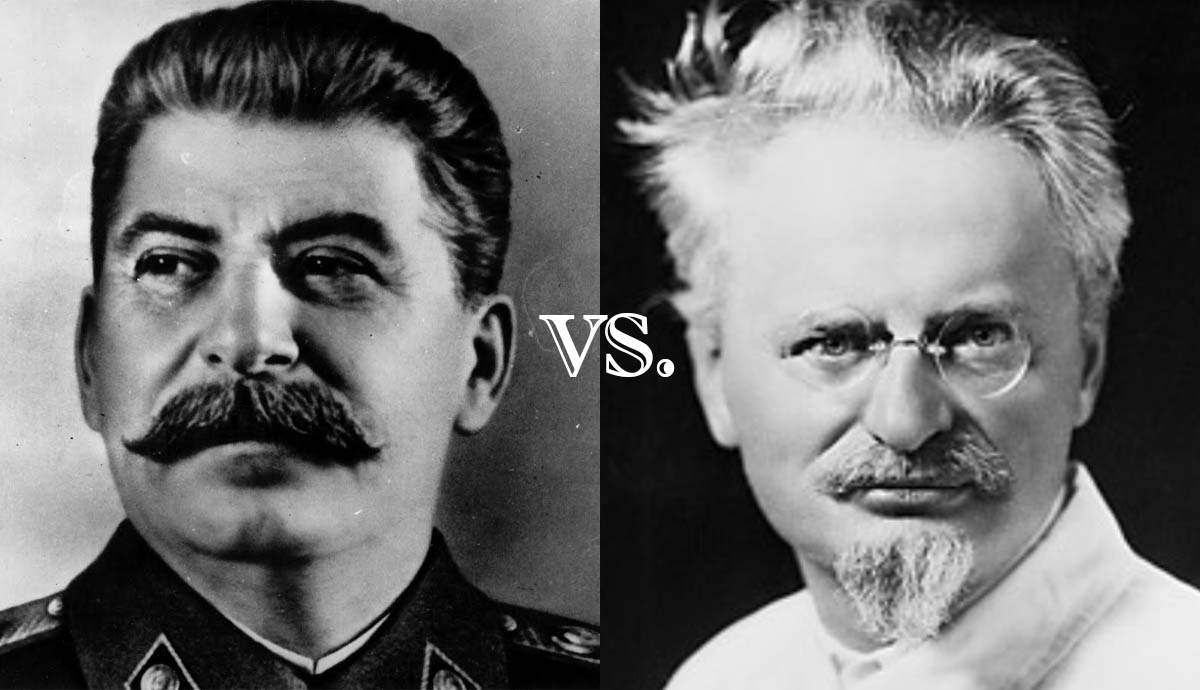

The years between 1921 and 1927, especially after Lenin’s death, saw a desperate struggle for power between Stalin and Trotsky. Lenin foresaw this struggle with great anxiety. He considered Trotsky abler but feared that he was overconfident; he knew that Stalin had concentrated enormous power in his hands through his role as party secretary, and he feared that he did not know how to use it. When he learned that Stalin had disobeyed his orders in smashing the Menshevik Republic of Georgia instead of reaching an accommodation with its leaders, he wrote angrily that Stalin should be removed from his post as general secretarv.

During these years Trotsky argued for a more highly trained managerial force in industry and for economic planning as an instrument that the state could use to control and direct social change. He favored the mechanization of agriculture and the weakening of peasant individualism by encouraging rural cooperatives. As Trotsky progressively lost power, he championed the right of individual communists to criticize the regime.

He also concluded that only through the outbreak of revolutions in other countries could the Russian socialist revolution be carried to its proper conclusion. Only if the industrial output and technical skills of the advanced Western countries could be put at the disposal of communism could Russia hope to achieve its own socialist revolution; either world revolution must break out or Russian socialism was doomed to failure.

Trotsky’s opponents found their chief spokesman in Nikolai Bukharin (1888-1938), the extremely influential editor of Pravda. A strong defender of NEP, Bukharin softened the rigorous Marxist doctrine of the class struggle by arguing that, since the proletarian state controlled the commanding heights of big capital, socialism was sure of success.

This view was not unlike the gradualist position taken by western European Social Democrats. Bukharin did not believe in rapid industrialization; he favored cooperatives, but opposed collectives in which (in theory) groups of peasants owned everything collectively. In foreign affairs, he was eager to cooperate abroad with noncommunist groups who might be useful to Russia. Thus he sponsored Soviet collaboration with China and with the German Social Democrats.

In his rise to power Stalin used Bukharin’s arguments to discredit Trotsky; then he adopted many of Trotsky’s policies and eliminated Bukharin. He came to favor rapid industrialization and to understand that this meant an unprecedentedly heavy capital investment. At the end of 1927 he shifted from his previous position on the peasantry and openly sponsored collectivization, since agricultural production was not keeping pace with industry. He declared that agriculture, like industry, must be transformed into a series of large-scale unified

enterprises.

Against Trotsky’s argument that socialism in one country was impossible, Stalin maintained that an independent socialist state could exist. This view did not imply abandoning the goal of world revolution, for Stalin maintained that the one socialist state (Russia) would inspire and assist communist movements everywhere. But, in his view, during the interim before the communists won elsewhere, Greater Russia could still exist and expand regionally as the only socialist state. In international relations, this doctrine allowed the Soviet Union to pursue a policy of “peaceful coexistence” with capitalist states when that seemed most useful or a policy of militant support of communist revolution when that seemed desirable. Stalin’s doctrine reflected his own Russian nationalism, rather than the more cosmopolitan and more Western views of Trotsky.

At the end of the civil war, Stalin was commissar of nationalities. In this post he dealt with the affairs of 65 million of the 140 million inhabitants of the new Russian Soviet Republic. He took charge of creating the new Asian “republics,” which enjoyed a degree of local self-government, programs of economic and educational improvement, and a chance to use their local languages and develop their own cultural affairs, so long as these were communist-managed.

In 1922 Stalin proposed the new Union of Socialist Soviet Republics as a substitute for the existing federation of republics. In the USSR, Moscow would control war, foreign policy, trade, and transport and would coordinate finance, economy, food, and labor. In theory, the republic would manage home affairs, justice, education, and agriculture. A Council of Nationalities, with an equal number of delegates from each ethnic group, would join the Supreme Soviet as a second chamber, thus forming the Central Executive Committee, which would appoint the Council of People’s Commissars—the government.

Stalin was also commissar of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate. Here his duties were to eliminate inefficiency and corruption from every branch of the civil service and to train a new corps of civil servants. His teams moved freely through all the offices of the government, observing and recommending changes. Although the inspectorate did not do what it was established to do, it did give Stalin control over thousands of bureaucrats and thus over the machinery of government.

Stalin was also a member of the Politburo—the tight little group of party bosses elected by the Central Committee, which included only five men throughout the civil war. Here his job was day-to-day management of the party. He was the only permanent liaison officer between the Politburo and the Orgburo, which assigned party personnel to their various duties in factory, office, or army units. Besides these posts, Stalin became general

secretary of the party’s Central Committee in 1922. Here he prepared the agenda for Politburo meetings, supplied the documentation for points under debate, and passed the decisions down to the lower levels. He controlled all party appointments, promotions, and demotions. He saw to it that local trade unions, cooperatives, and army units were under communists responsible to him. He had files on the loyalty and achievements of all managers of industry and other party members. In 1921 a Central Control Commission, which could expel party members for unsatisfactory conduct, was created; Stalin, as liaison between this commission and the Central Committee, now virtually controlled the purges, which were designed to keep the party pure.

In a centralized one-party state, a man of Stalin’s ambitions who held so many key positions had an enormous advantage in the struggle for power. Yet the state was so new, the positions so much less conspicuous than the ministry of war, held by Trotsky, and Stalin’s manner so often conciliatory that the likelihood of Stalin’s success did not become evident until it was too late to stop him.

Inside the Politburo he formed a three-man team with two other prominent Bolshevik leaders: the demagogue Gregory Zinoviev (1883-1936) and the expert on doctrine Leo Kamenev (1883-1936). Zinoviev was chairman of the Petrograd Soviet and boss of the Communist International; Kamenev was Lenin’s deputy and president of the Moscow Soviet.

The combination of Stalin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev proved unbeatable. The three used the secret pole to suppress all plots against them. They resisted Trc, sky’s demands for reform, which would have democratized the party to some degree and would have strengthened his position while weakening Stalin’s. They initiated the cult of Lenin immediately before his death and kept it burning fiercely thereafter, so that any suggestion for change coming from Trotsky seemed an act of impiety. They dispersed Trotsky’s followers by sending them to posts abroad.

Early in 1925 Stalin and his allies forced Trotsky to resign as minister of war. Soon thereafter the three-man team dissolved; Stalin allied himself with Bukharin and other right-wing members of the Politburo, to which he began to appoint his own followers. Using all his accumulated power, he beat his former allies on all questions of policy, and in 1926 they moved into a new but powerless alliance with Trotsky.

Stalin now deposed Zinoviev from the Politburo, charging him with plotting in the army. Next, Trotsky was expelled from the Politburo, and Zinoviev was ousted as president of the Comintern. In December 1927 a Communist party congress expelled Trotsky from the party and exiled him. Stalin had won.