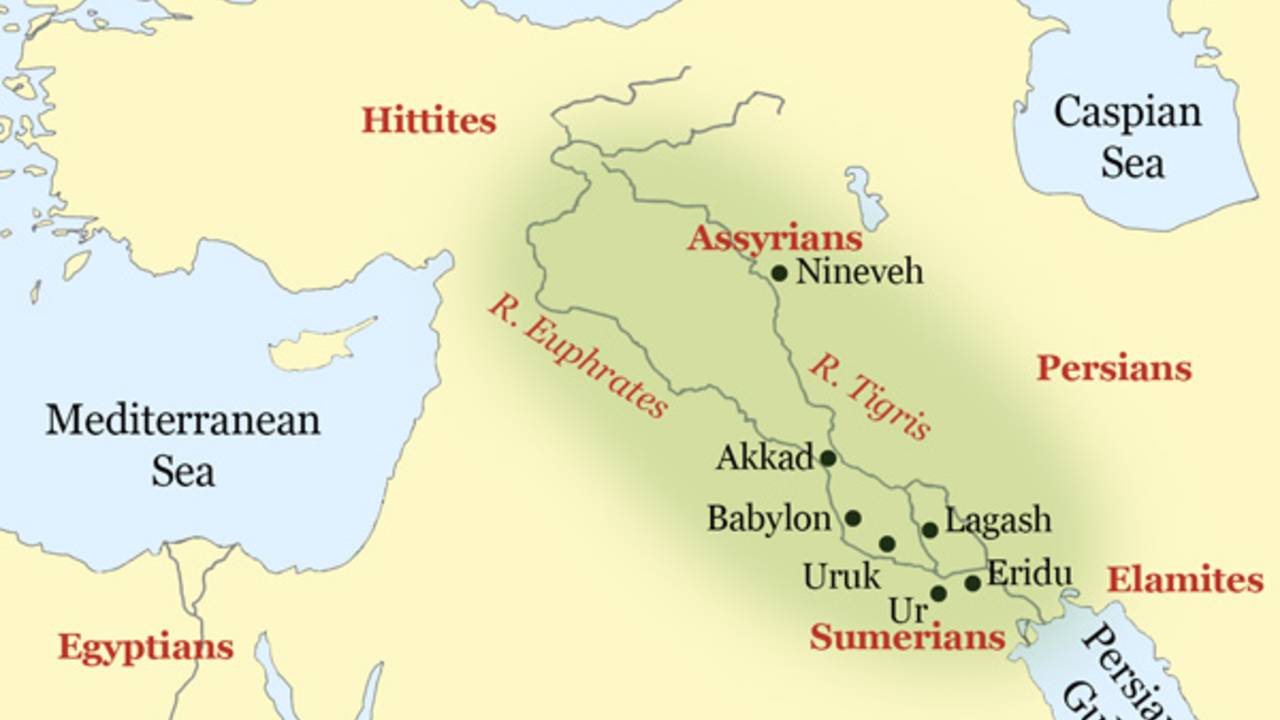

The successors of the Sumerians as rulers of Mesopotamia were the Babylonians and their successors, the Assyrians, both originally descended from nomads of the Arabian desert. Power first passed to them with Sargon the Great (2300 B.C.) and returned to them after an interlude (about 2000 B.C.) with the invasion from the west of a people called the Amorites.

Excavations at Mari in the middle Euphrates valley have turned up a palace with more than 260 rooms containing many thousands of tablets, mostly from the period between 1750 and 1700 B.C. These tablets were the royal archives, and they include letters to the king from local officials scattered throughout his territories and from rulers of other city-states. Among the correspondents was an Amorite prince named Hammurabi, who from c. 1792 to 1750 B.C., by warfare and diplomacy, made his Babylonian kingdom supreme in Mesopotamia and reunited it. His descendants retained Babylon and the area around it down to 1530, but had to give up Hammurabi’s great conquests.

Hammurabi’s code of law was applied from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea. Though modeled on its Sumerian predecessors, its punishments were much harsher. Inscribed on a pillar eight feet tall beneath a sculptured relief showing the king standing reverently before the seated sun god, the code reveals a strongly stratified society: A patrician who put out the eye of a patrician would have his own eye put out; a patrician who put out the eye of a plebeian only had to pay a fine. But even the plebeian had rights that, to some degree, protected him against violence from his betters. Polygamy and divorce were recognized. One clause says, “If a merchant lends silver to a trader without interest, and if the trader loses on his investment, he need return to the lender only the capital he has borrowed.” In its vocabulary as in its concept of the social order, the code reflects the continuing Sumerian impact on the Akkadian-speaking Babylonians.

Nomads from the east, the Kassites, shattered Babylonian power about 1530 B.C. After four centuries of relatively peaceful Kassite rule, supremacy in Mesopotamia gradually passed to the Assyrians, whose power had been rising, with occasional setbacks, for several centuries in their great northern city of Assur. About 1100 B.C. their ruler Tiglath-pileser reached both the Black Sea and the Mediterranean on a conquering expedition north and west. Assyrian militarism was harsh, and the conquerors regularly transported into captivity the entire population of defeated cities. By the eighth century B.C. the Assyrian state was a kind of dual monarchy; Tiglath-pileser III (744-727), its ruler, also took the title of ruler of Babylonia. He added enormous territory to the Neo-Assyrian Empire. But the mighty Assyrian Empire fell to a new power, the Medes, who took Nineveh in 612 B.C.

For less than a century thereafter (612-538 B.C.) Babylonia experienced a rapid, brilliant revival during which King Nebuchadnezzar built temples and palaces, made Babylon a wonder of the world with its famous hanging gardens, overthrew Jerusalem, and took the Hebrews into captivity. But in 539 King Belshazzar, having lost the support of the priesthood, had to surrender all of Babylonia to Cyrus the Great of Persia. The history of the Mesopotamian empires ended after 2,500 years. In religion as in all other aspects of life, the Baby-lonians and Assyrians took much from the Sumerians.

The cosmic gods remained the same, but the local gods were different; under Hammurabi one of them, Marduk, was exalted over all other gods and kept that supremacy thereafter. In Babylonian-Assyrian belief, demons became more numerous and more powerful, and a special class of priests was needed to fight them. Magic practices multiplied. All external events—an encounter with an animal, a sprained wrist, the position and color of the stars at a vital moment—had implications for one’s own future that needed to be discovered.

Starting with the observation of the stars for such magical purposes, the Babylonians developed substantial knowledge of celestial movement and the mathematics to go with it. They even

managed to predict eclipses. They could add, subtract, multiply, divide, and extract roots. They could solve equations and measure both plane areas and solid volumes. But their astronomy and their mathematics remained in the service of astrology and divination. So,

too, did jewelry making, goldsmithing, and ivory carving, which reached new and extraordinarily beautiful heights.