In the new kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, proclaimed in December 1918, there came together for the first time in one state the former south-Slav subjects of Austria and Hungary with those of the former kingdom of Serbia.

This was in most respects a satisfactory state from the territorial point of view; revisionism therefore was not a major issue. But the new state had to create a governmental system that would satisfy the aspirations of each of its nationality groups. Over this problem democracy broke down and a dictatorship was established.

Serbian political ambitions had helped to start World War I. The Serbs were more numerous than Croats and Slovenes together, and many Serbs felt that the new kingdom should be the “greater Serbia” of which they had so long dreamed. Orthodox in religion, using the Cyrillic alphabet, and having experienced and overthrown Ottoman domination, Serbs tended to look down on the Croats. Roman Catholic in religion, using the Latin alphabet, and having opposed Germans and Magyars for centuries, Croats tended to feel that the Serbs were crude Easterners who ought to give them a full measure of autonomy within the new state. The battle lines were drawn: Serb-sponsored centralism against Croat-sponsored federalism.

The Croats, under their peasant leader Stephen RadiC (1871-1928), boycotted the constitutent assembly of 1920, and the Serbs put through a constitution providing for a strongly centralized state. Both sides refused to compromise, and when Radk was murdered on the floor of parliament in June 1928, a crisis arose that ended only when King Alexander II (r. 1921-1934) proclaimed a royal dictatorship in January 1929.

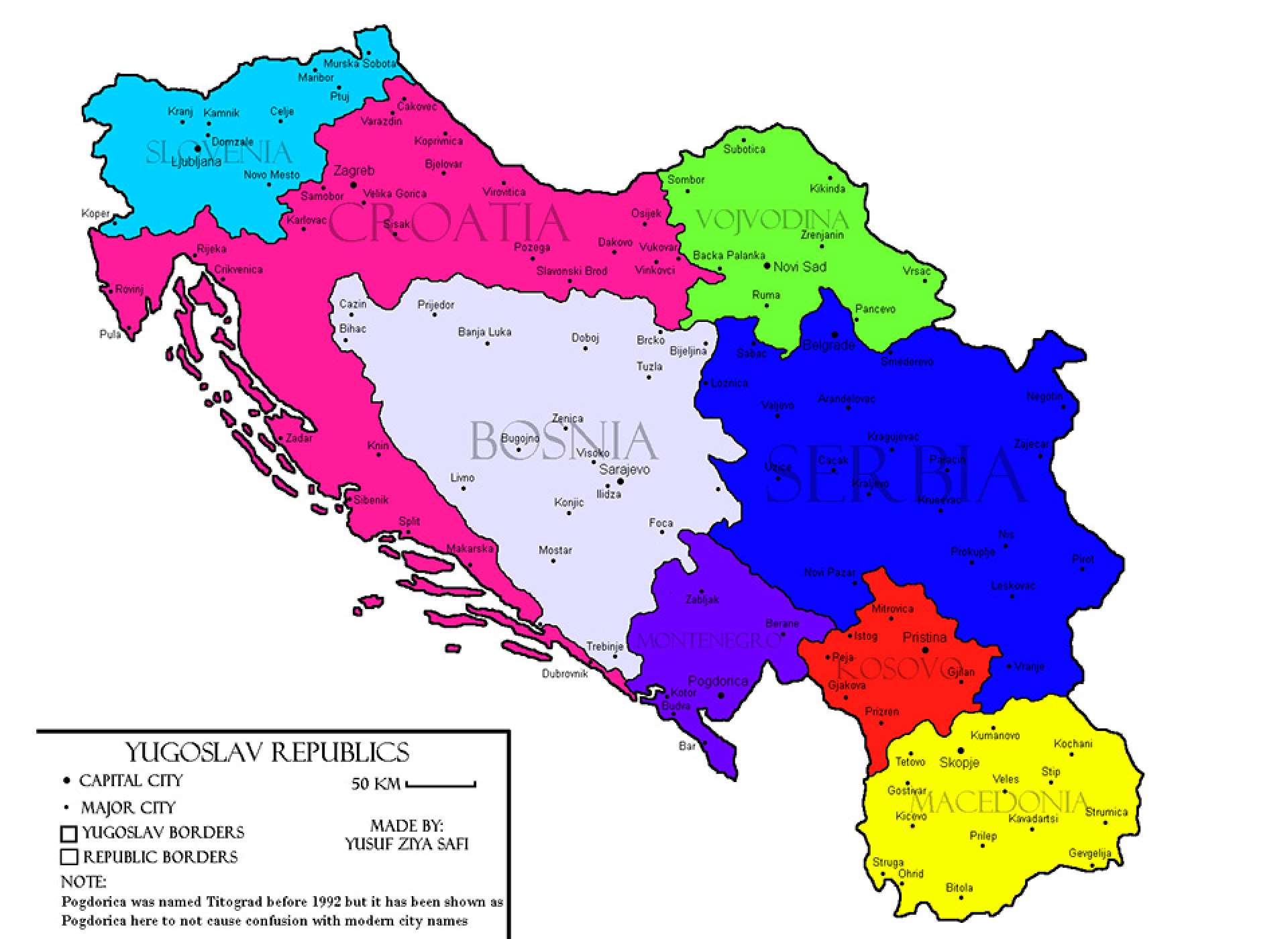

Alexander tried to settle the problem by erasing old provincial loyalties. There would be no more Serbia or Croatia but new administrative units named after the chief rivers that ran through them. The whole country was renamed Yugoslavia, as a sign that there were to be no more Serbs and Croats. But it was still a Serbian government, and the Croats would not forget it. Elections were rigged by the government, and all political parties were dissolved.

One result was to strengthen Croat extremists who had wanted an independent Croatia in the days of the Habsburgs, and who now combined this demand with terrorism, supported by the enemies of Yugoslavia—Italy and Hungary. The Croat extremists were called Ustashi (Rebels), and they were assisted by Mussolini.

The Ustashi were deeply involved in the assassination of Alexander during a state visit to France in October 1934. Under the regency of Alexander’s cousin, the dictatorship continued. In the summer of 1939 an agreement was reached with the Croats that established an autonomous Croatia. But by then it was too late, for war soon engulfed the Balkans.