V-J Day, the day of victory over Japan, was now the all out goal of Allied effort. The Soviet Union had refrained from adding Japan to its formal enemies as long as Germany was still a threat. Britain and the United States, on the other hand, were anxious for the Soviets to enter the war against the Japanese. This desire was responsible for many of the concessions made to Stalin in the last months of the German war.

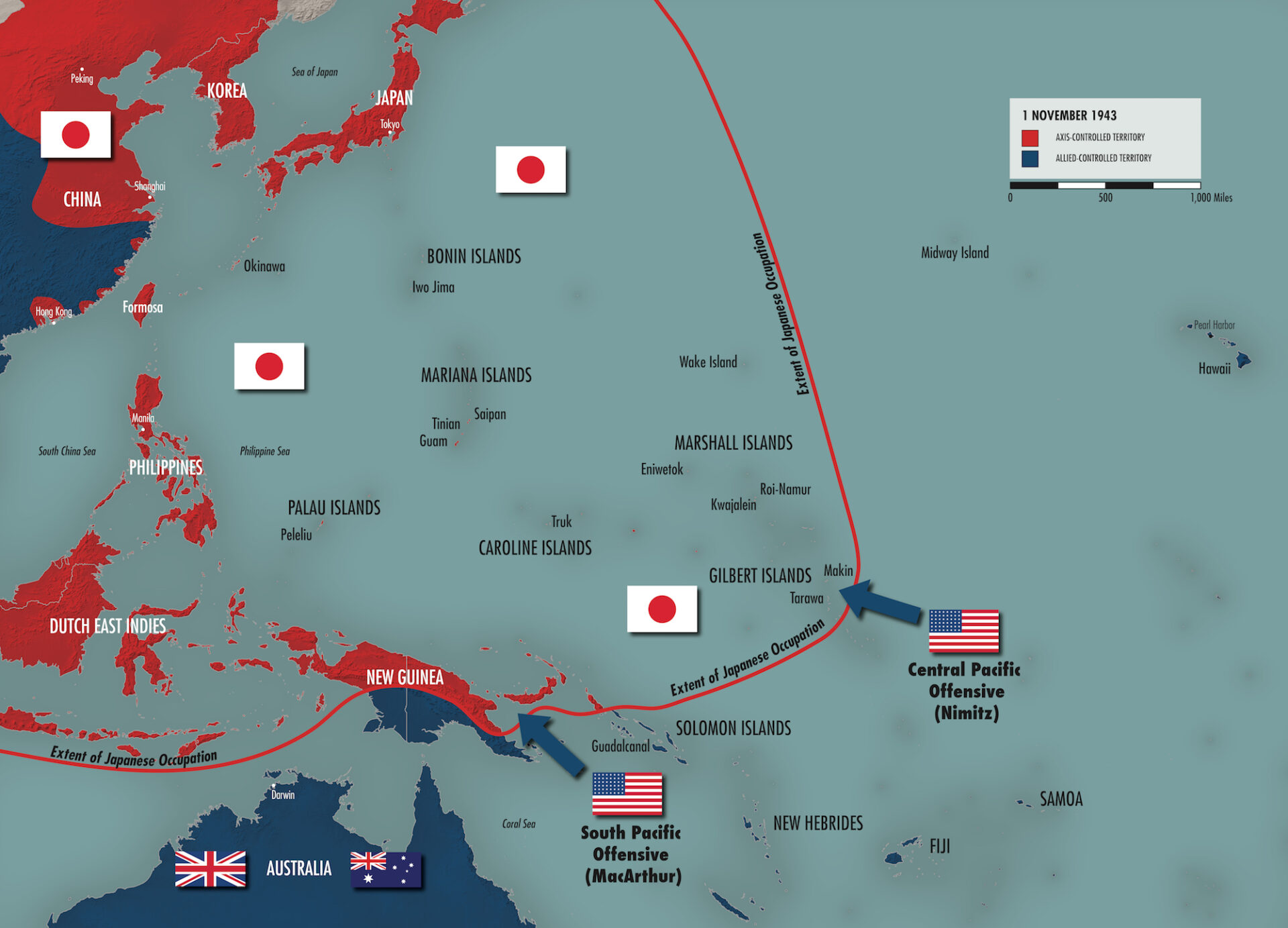

The attack on Japan had been pressed in three main directions. First, in a process that the American press soon called “island-hopping,” the American navy drove straight toward Japan from the central Pacific. One after another, the small island bases that stood in the way were reduced by American naval forces, which used both air support and amphibious methods. Each island required an intense beach assault and pitched battle: Tarawa, Eniwetok, Kwajalein, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Saipan, and Guam.

Second, the Americans and Australians, with help from other Commonwealth elements, worked their way up the southwest Pacific through the much larger islands of the Solomons, New Guinea, and the Philippines. The base for this campaign—which was under the command of the American general Douglas MacArthur (1880– 1964)—was Australia and such outlying islands as New Caledonia and the New Hebrides. By October 1944 the sea forces had won the battle of the Philippine Sea and had made possible the successful landing of MacArthur’s troops on Leyte and the reconquest of the Philippine Islands from the Japanese.

The third attack came from the south in the China-Burma-India theater. The main effort of the Allies was to get material support to Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalists at Chungking and, if possible, to weaken the Japanese position in Burma, Thailand, and Indochina. After Pearl Harbor, when the Japanese seized and shut the “Burma Road,” the only way for the Allies to communicate with

Chiang’s Nationalists was by air. Although the Western Allies did not invest an overwhelming proportion of their resources in the China-Burma-India theater, they did help keep the Chinese formally in the fight. And as the final campaign of 1945 drew on, the British, with Chinese and American aid, were holding down three Japanese field armies in this theater.

The end in Japan came with a suddenness that was hardly expected. From Pacific island bases, American airplanes had inflicted crippling damage on Japanese industry in the spring and summer of 1945. The Japanese fleet had been almost destroyed, submarine warfare had almost strangled the Japanese economy, and the morale of Japanese troops was declining. Nonetheless, American leaders were convinced that only the use of their recently invented atom bomb could avert the very heavy casualties expected from the proposed amphibious invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Some commentators believe that racism also played a role in the decision to use the bomb on the Japanese rather than on any European people, though the bomb was not, in fact, ready for use in time to affect the European war. An additional motive for its use was a desire to demonstrate to the Soviet Union, which many feared would turn upon the Allies at the end of the war, just how powerful America’s new weapon was. The result was the dropping of the first atom bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

On August 8 the Soviets, who had agreed to come into the war against Japan once Germany was beaten, invaded Manchuria in full force. Faced with what they felt was certain defeat after the dropping of a second atom bomb on Nagasaki, the Japanese government decided not to make a last-ditch stand in their own country.

On September 2 the Japanese formally surrendered in Tokyo Bay. Japan gave up its conquests abroad and submitted to American military occupation. Purged of most of its militarists, the Japanese government continued to rule under nominal Allied (actually American) supervision.