The event that defeated Napoleon’s great designs was the French debacle in Russia. French actions after 1807 soon convinced Czar Alexander that Napoleon was not keeping the Tilsit bargain and was intruding on Russia’s sphere in eastern Europe.

When Alexander and Napoleon met again at the German town of Erfurt in 1808, they could reach no agreement. For Alexander, French acquisitions from Austria in 1809 raised the unpleasant prospect of French domination over the Balkans, and the transfer of Galicia from Austria to the grand duchy of Warsaw suggested that this Napoleonic vassal might next seek to absorb Russia’s acquisitions from the partitions of Poland.

Meanwhile, Napoleon’s insistent efforts to make Russia enforce the Continental System increasingly angered Alexander. These grievances caused a break between the czar and the emperor and led to the invasion of Russia by the French in 1812.

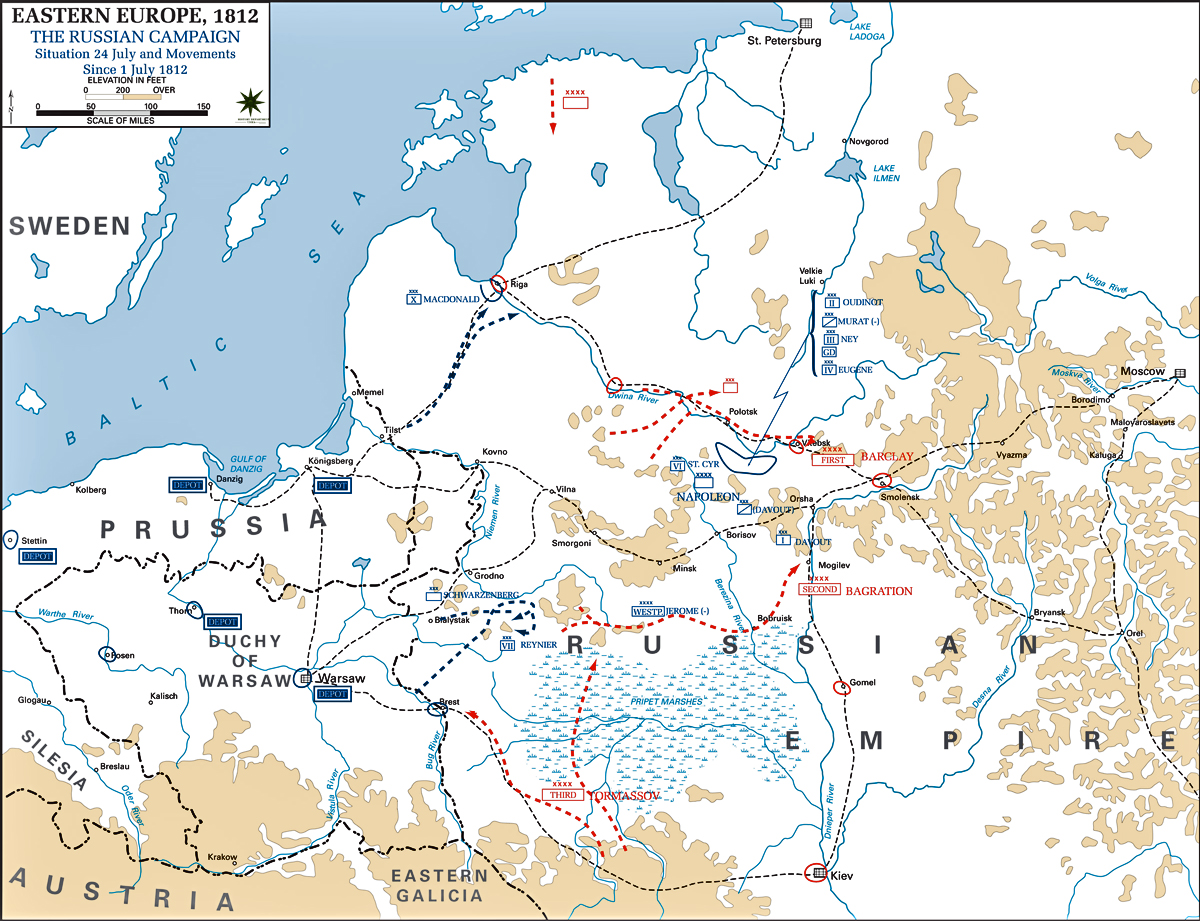

For the invasion Napoleon assembled nearly 700,000 men, most of whom were unwilling conscripts. The supply system for so distant a campaign broke down almost immediately, and the Russian scorched-earth policy made it hard for soldiers to live off the land and impossible for horses to get fodder, so that many of them had to be destroyed. As the army marched eastward, one of Napoleon’s aides reported:

There were no inhabitants to be found, no prisoners to be taken, not a single straggler to be picked up. We were in the heart of inhabited Russia and yet we were like a vessel without a compass in the midst of a vast ocean, knowing nothing of what was happening around us.*

Napoleon had hoped to strike a quick knockout blow, but the battle of Borodino was indecisive. Napoleon entered Moscow and remained in the burning city for five weeks (September—October 1812) in the vain hope of bringing Czar Alexander to terms.

But Russian stubbornness, typhus, and the shortage of supplies forced Napoleon to begin a nightmare retreat. Ill-fed, inadequately clothed and sheltered, without medical help, the retreating soldiers suffered horribly. Less than a quarter of the army survived the retreat from Moscow; the rest had been taken prisoner or had died of wounds, starvation, disease, or had frozen to death.