The Church of Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) in Constantinople, built in the sixth century, was designed to be “a church the like of which has never been seen since Adam nor ever will be.” The dome, says a contemporary, “seems rather to hang by a golden chain from heaven than to be supported by solid masonry.”

Justinian, the emperor who built it, was able to exclaim, “I have outdone thee, 0 Solomon!” The Turks themselves, who seized the city in 1453, have ever since paid Hagia Sophia the compliment of imitation; the great mosques that throng present-day Istanbul are all more or less directly copied after the great church of the Byzantines.

Before Hagia Sophia could be built, other cities of the Empire, particularly Alexandria, Antioch, and Ephesus, had produced an architectural synthesis of the Hellenistic or Roman basilica with a dome taken from the Persians. This is just one striking example of how Greek and oriental elements were to be blended in Byzantine society. In decoration, the use of brilliantly colored marble, enamel, silk and other fabrics, gold, silver, jewels, and paintings and glowing mosaics on the walls and ceilings reflect the sumptuousness of the orient.

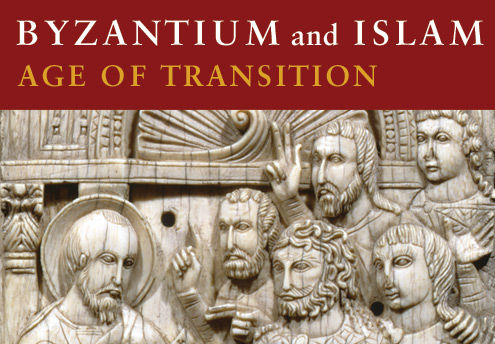

Along with the major arts of architecture, painting, and mosaics went the so-called minor arts. The silks, the ivories, the work of the goldsmiths and silversmiths, the enamel and jeweled bookcovers, the elaborate containers made to hold the relics of a saint, the great Hungarian sacred Crown of Saint Stephen, the superb miniatures of the illuminated manuscripts in many European libraries— all testify to the endless variety and fertility of Byzantine inspiration.

Even in those parts of western Europe where Byzantine political authority had disappeared, the influence of this Byzantine artistic flowering is often apparent. Sometimes actual creations by Byzantine artists were produced in the West or ordered from Constantinople by a connoisseur; these are found in Sicily and southern Italy, in Venice, and in Rome.

Sometimes the native artists worked in the Byzantine manner, as in Spain, in Sicily, and in the great Romanesque domed churches of southern France. Often the native product was not purely Byzantine, but rather a fusion of Byzantine with local elements.