This regime was well designed to carry on the chief preoccupation of the emerging Roman state war. The Roman army at first had as its basic unit the phalanx- about 8,000 foot soldiers armed with helmet, shield, lance, and sword. But experience led to the substitution of the far more maneuverable legion, consisting of 5,000 men in groups of 60 or 120, called maniples, armed with an iron-tipped javelin, which could be hurled at the enemy from a distance. Almost all citizens of Rome had to serve. Iron discipline prevailed; but the officers also understood the importance of generous reward of bravery.

In a long series of wars, the Romans established their political dominance over the other Latin towns, the Etruscan cities, and the tribes of central Italy. Early in the third century B.C. they conquered the Greek cities of southern Italy. Meanwhile, in the north, a Celtic people, the Gauls, had crossed the Alps and settled in the Lombard plain. Their expansion was halted in 225 B.C. at the little river Rubicon, which was then the northern frontier of Roman dominion.

In conquered areas the Romans sometimes planted a colony of their own land-hungry plebeians. Usually they did not try to force the resident population into absolute subjection, accepting them as allies and respecting their institutions. Some of the nearest neighbors of Rome became full citizens of the Republic, but more often they had the protection of Roman law while being unable to participate in the Roman assemblies.

The conquest of Magna Graecia made Rome a near neighbor of the Carthaginian state. Carthage (modern Tunis) was originally a Phoenician colony but had long since liberated itself and expanded along the African and Spanish shores of the Mediterranean and into western Sicily. When the Carthaginians began to attack the Greek cities in eastern Sicily, the Sicilian Greeks appealed to Rome. So the Romans launched the First Punic (from the Latin word for Phoenician) War (264-241 B.C.).

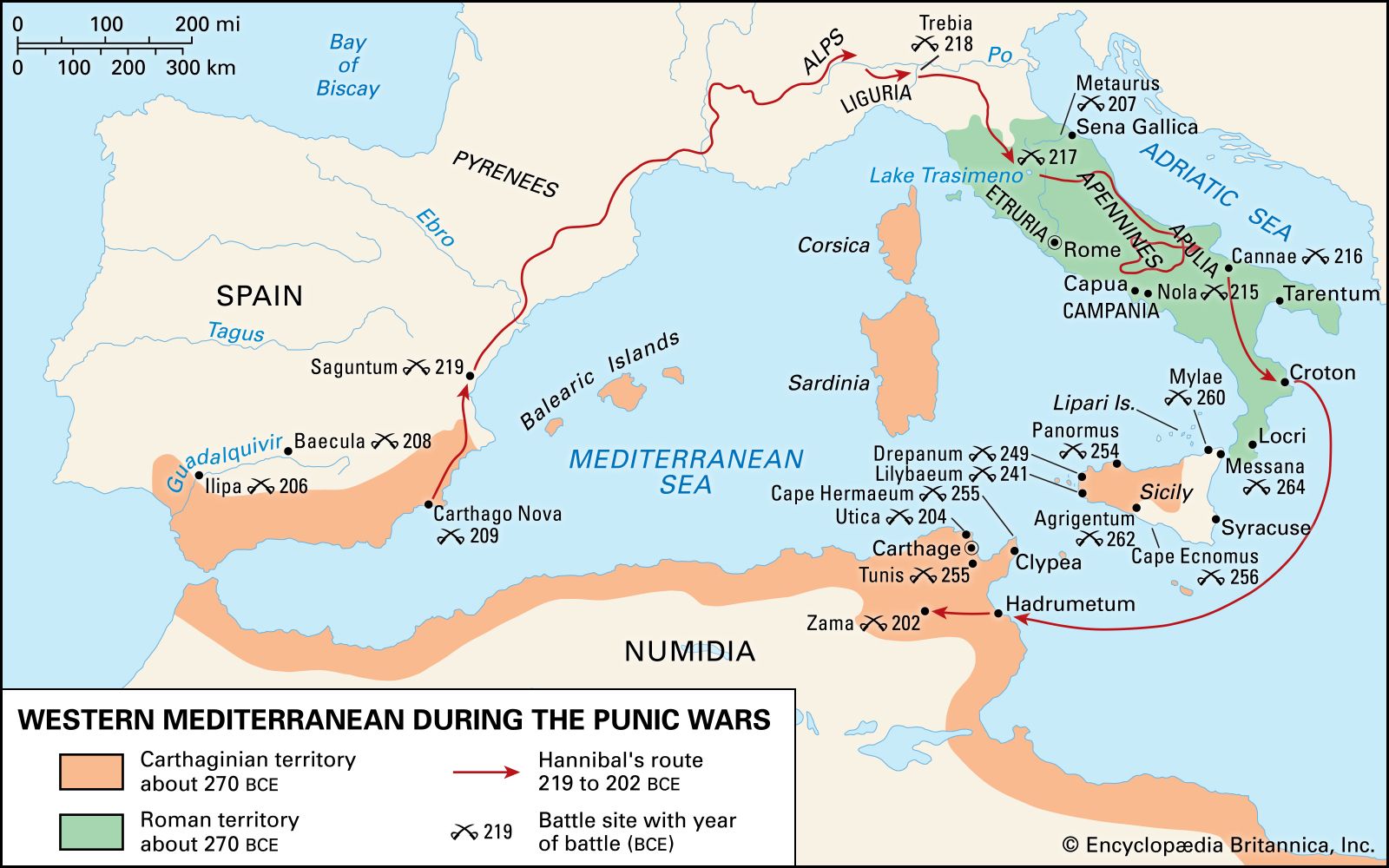

The Romans won that war by building their first major fleet and defeating the Carthaginians at sea. They forced Carthage to give up all claim to eastern Sicily and to cede western Sicily as well, thus obtaining their first province beyond the Italian mainland. Sardinia and Corsica followed in 237. Seeking revenge, the Carthaginians used Spain as the base for an overland invasion to Italy in the Second Punic War (218-202). Their commander, Hannibal (247-183), led his forces across southern Gaul and then over the Alps into Italy. In northern Italy he recruited many Gauls and, making brilliant use of light infantry, won a string of victories as he marched southward.

Gradually the Romans rebuilt their armies, and in 202 B.C. Hannibal was summoned home to defend Carthage against a Roman invading force under Scipio, who had captured the Punic centers in Spain. Scipio won the battle at Zama, in Numidia, and the title Africanus (Conqueror of Africa) as a reward. The Romans forced the Carthaginians to surrender Spain (where the local population resisted Roman rule for another two centuries), to pay a large levy, and to promise to follow Rome’s lead in foreign policy. Hannibal escaped to the court of the Seleucid king Antiochus III.

Though Carthaginian power had been broken, the city quickly recovered its prosperity. This alarmed the war parry at Rome. Cato, a censor and senator, ended each of his speeches with the words Delenda est Carthago (Carthage must be destroyed). In the Third Punic War (149-146) the Romans leveled the city, sprinkled salt on the earth, and took over all the remaining Carthaginian territory.

While the Punic Wars were still going on, Rome had become embroiled in the Balkans and in Greece, first sending ships and troops to put down pirates in the Adriatic and then intervening again in 219 to punish an unruly local ally. The Greeks were grateful to Rome and admitted Romans to the Eleusinian mysteries and the Isthmian Games. But Philip V (221-179), Antigonid king of Macedon, viewed with suspicion Roman operations on his side of the Adriatic. He tried to help Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but a Roman fleet prevented him from crossing to Italy. Many of the Greek cities came to Rome’s aid in the fighting that ensued. In this First Macedonian War (215-205), Philip was defeated.

Not eager as yet to expand on the eastern shores of the Adriatic, Rome contented itself with establishing a series of Illyrian buffer states. But Philip kept intervening in these states, and the Romans feared for their loyalty. In 202 B.C. several Hellenistic powers—Ptolemy V of Egypt; his ally Attalus, king of the powerful independent kingdom of Pergamum in Asia Minor; and Rhodes, head of a new naval league—as well as Athens, appealed to Rome to intervene once more against Philip V. Furthermore, the Romans feared the alliance struck between Philip and Antiochus III. In the Second Macedonian War (200-197) Rome defeated Philip’s armies on their own soil and forced him to withdraw from Greece altogether and become an ally of Rome.

Antiochus III had profited by the defeat of Macedon, taking over the Greek cities on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor and crossing into Europe. Hoping to keep Greece as a buffer against him and worried at this advance, the Romans kept on negotiating with him. But Antiochus, who had with him the refugee Hannibal, opposed the Romans in Greece. The Romans defeated Antiochus and then invaded Asia, forcing him to surrender all the Seleucid holdings in Asia Minor in 188. Hannibal escaped but poisoned himself in 183 as he was about to be surrendered to Rome. Rome had become the predominant power in the Greek world.

For the next forty years the Romans felt obliged to arbitrate the constantly recurring quarrels among the Greek states. In the Third Macedonian War (172-168), Perseus, Philip V’s son and successor, was captured and his forces routed at the decisive battle of Pydna. Rome imposed a ruthless settlement, breaking Macedon up into four republics and exiling many who had sympathized with Perseus. Twenty years later the Romans annexed Macedon, their first province east of the Adriatic. In 146 they defeated a desperate uprising of the Achaean League and marked their victory by a brutal sack of Corinth, in which the men were killed, the women and children sold as slaves, and the city leveled.

The Romans henceforth dominated Greece from Macedon, but did not yet annex it as a province. Internal fighting in Greece came to an end; there was a religious and economic revival; divisions between rich and poor became more pronounced. Rome’s prestige was now so great that in 133 the king of Pergamum, left his flourishing Asia Minor state to Rome in his will. It became the new province of Asia.