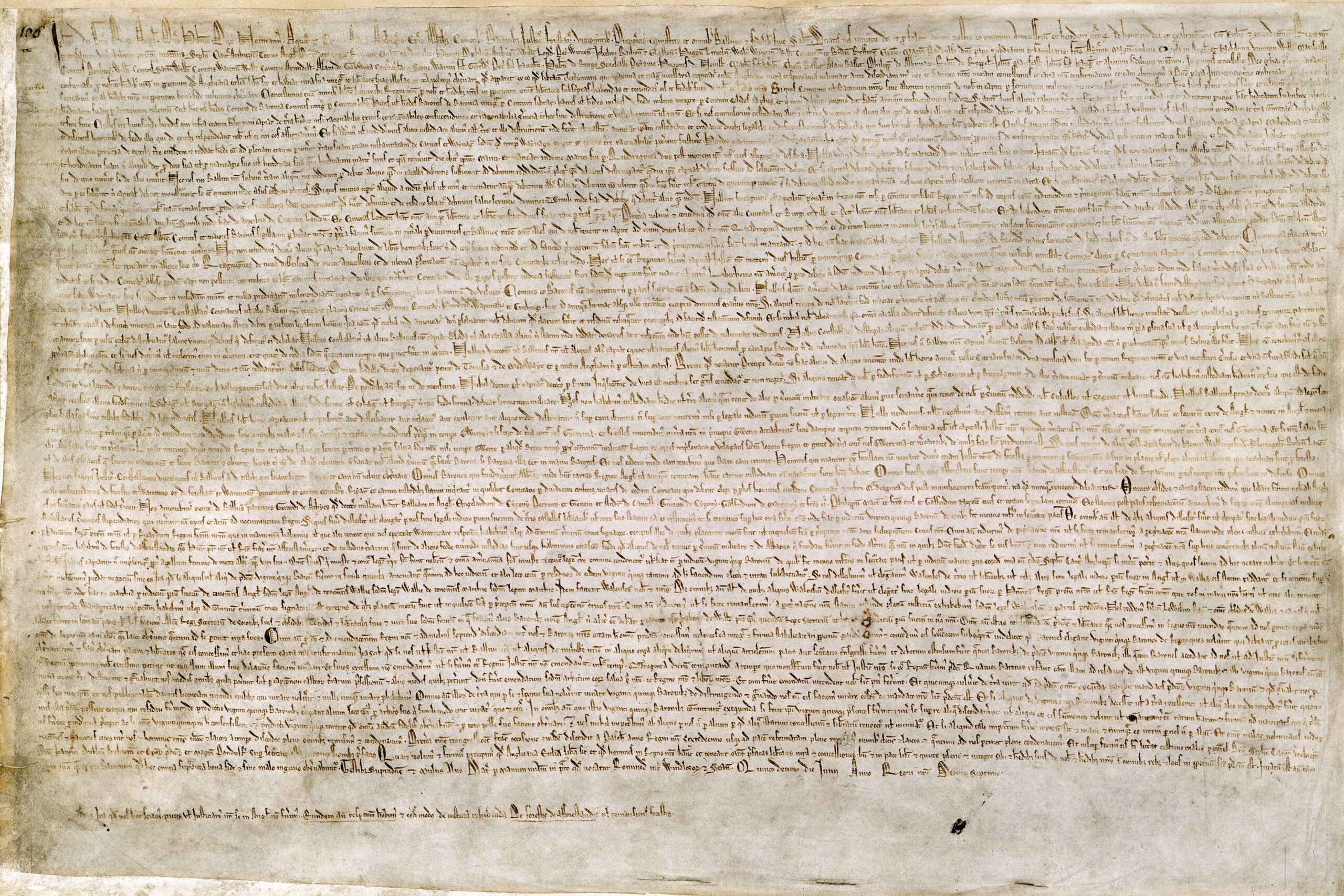

A quarrel with perhaps a third of the English barons arose from John’s ruthlessness in raising money for the campaign in France and from his practice of punishing vassals without trial. The barons hostile to John renounced their homage to him and drew up a list of demands, most of which they forced him to accept on June 15, 1215, at a meadow called Runnymede on the banks of the Thames. The document that he agreed to send out under the royal seal to all the shires in England had sixty-three chapters, in the legal form of a feudal grant or conveyance, known as Magna Carta, the “Great Charter.”

Magna Carta was a feudal document, a list of specific commissions drawn up in the interest of a group of barons at odds with their feudal lord, the king. The king promised reform and made certain concessions to the peasantry, the tradespeople, and the church. This medieval document is often called the foundation stone of present liberties in Britain and North America largely because some of its provisions were given new and expanded meanings in later centuries. For instance, the provision that “No scutage or aid, save the customary feudal ones, shall be levied, except by the common consent of the realm” in 1215 meant only that John would have to consult his great council (barons and bishops) before levying extraordinary feudal aids.

Yet this could later be expanded into the doctrine that all taxation must be by consent, that taxation without representation was tyranny—which would have astonished everyone at Runnymede. Similarly, the provision that “No freeman shall be arrested or imprisoned, or dispossessed or outlawed or banished or in any way molested; nor will we set forth against him, nor send against him, unless by the lawful judgment of his peers and by the law of the land” in 1215 meant only that the barons did not want to be tried by anybody not their social equal, and they wished to curb the aggressions of royal justice. Yet it was later expanded into the doctrine of due process of law, that everyone is entitled to a trial by “his peers.”

Although medieval kings of England reissued the charter with modifications some forty times, it was to be ignored under the Tudors in the sixteenth century, and it was not appealed to until the revolt against the Stuarts in the seventeenth century. By then the rebels against Stuart absolutism could read into Magna Carta many of the same modern meanings that we see in them at first glance. Thus Magna Carta’s lasting importance lies partly in what later interpreters were able to find in its original clauses. It also lies, perhaps even more, in two general principles underlying the whole document: that the king was subject to the law and that he might, if necessary, be forced to observe it.

As soon as John had accepted the charter, he tried to break his promises. The pope declared the charter null and void, and Langton and the barons opposed to John became supporters of a French monarchy for England. Philip Augustus’s son actually occupied London briefly; but John died in 1216 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son, Henry III (r. 1216-1272), to whose side the barons rallied. The barons expelled the French from England, and it was not until 1258 that the king found himself again in an open clash with a faction of his own barons.

Henry reissued Magna Carta, formally ratifying it. Nonetheless, the barons felt that he did not fully adhere to it. The clash came to a head in 1258, a year of bad harvest, when Henry asked for one third of the revenues of England as an extra grant for the pope. The barons came armed to the session of the great council and secured the appointment of a committee of twenty-four of their number, who then issued a document known as the Provisions of Oxford. This document created a council of fifteen without whose advice the king could do nothing. The committee put its own men in the high offices of state, and it replaced the full great council with a baronial body of twelve.

But the barons could not agree among themselves, and Henry III resumed his personal rule. Open civil war broke out in 1263 between the king and the baronial party headed by Simon de Montfort (c. 1208-1265). When in the next year Louis IX was called in to arbitrate, he ruled in favor of the king and against the barons. Simon, however, would not accept the decision.

He captured the king and set up a regime of his own, based on the restoration of the Provisions of Oxford. This regime lasted fifteen months. In 1265 Simon called an assembly of his supporters, but the heir to the throne, Prince Edward, defeated and killed Simon and restored his father, Henry III, to the throne. For the last seven years of Henry’s reign (1265-1272), as well as for the next thirty-five years of his own rule (1272-1307), Edward I was the true ruler of England.